The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and Russia's Early Soviet Regime

In the night of July 16-17, 1918, a squad of Bolshevik secret police murdered Russia's last emperor, Tsar Nicholas II, along with his wife, Tsaritsa Alexandra, their 14-year-old son, Tsarevich Alexis, and their four daughters.

They were cut down in a hail of gunfire in a half-cellar room of the house in Ekaterinburg, a city in the Ural mountain region, where they were being held prisoner. The daughters were finished off with bayonets. To prevent a cult for the dead Tsar, the bodies were carted away to the countryside and hastily buried in a secret grave.

Bolshevik authorities at first reported that the Romanov emperor had been shot after the discovery of a plot to liberate him. For some time the deaths of the Empress and the children were kept secret. Soviet historians claimed for many years that local Bolsheviks had acted on their own in carrying out the killings, and that Lenin, founder of the Soviet state, had nothing to do with the crime.

In 1990, Moscow playwright and historian Edvard Radzinsky announced the result of his detailed investigation into the murders. He unearthed the reminiscences of Lenin's bodyguard, Alexei Akimov, who recounted how he personally delivered Lenin's execution order to the telegraph office. The telegram was also signed by Soviet government chief Yakov Sverdlov. Akimov had saved the original telegraph tape as a record of the secret order.1

Radzinsky's research confirmed what earlier evidence had already indicated. Leon Trotsky -- one of Lenin's closest colleagues -- had revealed years earlier that Lenin and Sverdlov had together made the decision to put the Tsar and his family to death.

Recalling a conversation in 1918, Trotsky wrote: 2

Recalling a conversation in 1918, Trotsky wrote: 2

My next visit to Moscow took place after the [temporary] fall of Ekaterinburg [to anti-Communist forces]. Speaking with Sverdlov, I asked in passing: "Oh yes, and where is the Tsar?""Finished," he replied. "He has been shot.""And where is the family?""The family along with him.""All of them?," I asked, apparently with a trace of surprise."All of them," replied Sverdlov. "What about it?" He was waiting to see my reaction. I made no reply."And who made the decision?," I asked."We decided it here. Ilyich [Lenin] believed that we shouldn't leave the Whites a live banner to rally around, especially under the present difficult circumstances."I asked no further questions and considered the matter closed.

Recent research and investigation by Radzinsky and others also corroborates the account provided years earlier by Robert Wilton, correspondent of the London Times in Russia for 17 years. His account, The Last Days of the Romanovs - originally published in 1920, and reissued in 1993 by the Institute for Historical Review -- is based in large part on the findings of a detailed investigation carried out in 1919 by Nikolai Sokolov under the authority of "White" (anti-Communist) leader Alexander Kolchak. Wilton's book remains one of the most accurate and complete accounts of the murder of Russia's imperial family.3

A solid understanding of history has long been the best guide to comprehending the present and anticipating the future. Accordingly, people are most interested in historical questions during times of crisis, when the future seems most uncertain. With the collapse of Communist rule in the Soviet Union, 1989-1991, and as Russians struggle to build a new order on the ruins of the old, historical issues have become very topical. For example, many ask: How did the Bolsheviks, a small movement guided by the teachings of German-Jewish social philosopher Karl Marx, succeed in taking control of Russia and imposing a cruel and despotic regime on its people?

In recent years, Jews around the world have been voicing anxious concern over the specter of anti-Semitism in the lands of the former Soviet Union. In this new and uncertain era, we are told, suppressed feelings of hatred and rage against Jews are once again being expressed. According to one public opinion survey conducted in 1991, for example, most Russians wanted all Jews to leave the country.4 But precisely why is anti-Jewish sentiment so widespread among the peoples of the former Soviet Union? Why do so many Russians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians and others blame "the Jews" for so much misfortune?

A Taboo Subject

Although officially Jews have never made up more than five percent of the country's total population,5 they played a highly disproportionate and probably decisive role in the infant Bolshevik regime, effectively dominating the Soviet government during its early years. Soviet historians, along with most of their colleagues in the West, for decades preferred to ignore this subject. The facts, though, cannot be denied.

With the notable exception of Lenin (Vladimir Ulyanov), most of the leading Communists who took control of Russia in 1917-20 were Jews. Leon Trotsky (Lev Bronstein) headed the Red Army and, for a time, was chief of Soviet foreign affairs. Yakov Sverdlov (Solomon) was both the Bolshevik party's executive secretary and -- as chairman of the Central Executive Committee -- head of the Soviet government. Grigori Zinoviev (Radomyslsky) headed the Communist International (Comintern), the central agency for spreading revolution in foreign countries. Other prominent Jews included press commissar Karl Radek (Sobelsohn), foreign affairs commissar Maxim Litvinov (Wallach), Lev Kamenev (Rosenfeld) and Moisei Uritsky.6

Lenin himself was of mostly Russian and Kalmuck ancestry, but he was also one-quarter Jewish. His maternal grandfather, Israel (Alexander) Blank, was a Ukrainian Jew who was later baptized into the Russian Orthodox Church.7

A thorough-going internationalist, Lenin viewed ethnic or cultural loyalties with contempt. He had little regard for his own countrymen. "An intelligent Russian," he once remarked, "is almost always a Jew or someone with Jewish blood in his veins."8

Critical Meetings

In the Communist seizure of power in Russia, the Jewish role was probably critical.

Two weeks prior to the Bolshevik "October Revolution" of 1917, Lenin convened a top secret meeting in St. Petersburg (Petrograd) at which the key leaders of the Bolshevik party's Central Committee made the fateful decision to seize power in a violent takeover.

Of the twelve persons who took part in this decisive gathering, there were four Russians (including Lenin), one Georgian (Stalin), one Pole (Dzerzhinsky), and six Jews.9

Of the twelve persons who took part in this decisive gathering, there were four Russians (including Lenin), one Georgian (Stalin), one Pole (Dzerzhinsky), and six Jews.9

To direct the takeover, a seven-man "Political Bureau" was chosen.

It consisted of two Russians (Lenin and Bubnov), one Georgian (Stalin), and four Jews (Trotsky, Sokolnikov, Zinoviev, and Kamenev).10

Meanwhile, the Petersburg (Petrograd) Soviet -- whose chairman was Trotsky -- established an 18-member "Military Revolutionary Committee" to actually carry out the seizure of power. It included eight (or nine) Russians, one Ukrainian, one Pole, one Caucasian, and six Jews.11 Finally, to supervise the organization of the uprising, the Bolshevik Central Committee established a five-man "Revolutionary Military Center" as the Party's operations command. It consisted of one Russian (Bubnov), one Georgian (Stalin), one Pole (Dzerzhinsky), and two Jews (Sverdlov and Uritsky).12

Contemporary Voices of Warning

Well-informed observers, both inside and outside of Russia, took note at the time of the crucial Jewish role in Bolshevism. Winston Churchill, for one, warned in an article published in the February 8, 1920, issue of the London Illustrated Sunday Herald that Bolshevism is a "worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilization and for the reconstitution of society on the basis of arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality."

The eminent British political leader and historian went on to write:13

The eminent British political leader and historian went on to write:13

There is no need to exaggerate the part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution by these international and for the most part atheistical Jews. It is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from the Jewish leaders. Thus Tchitcherin, a pure Russian, is eclipsed by his nominal subordinate, Litvinoff, and the influence of Russians like Bukharin or Lunacharski cannot be compared with the power of Trotsky, or of Zinovieff, the Dictator of the Red Citadel (Petrograd), or of Krassin or Radek -- all Jews. In the Soviet institutions the predominance of Jews is even more astonishing. And the prominent, if not indeed the principal, part in the system of terrorism applied by the Extraordinary Commissions for Combatting Counter-Revolution [the Cheka] has been taken by Jews, and in some notable cases by Jewesses.Needless to say, the most intense passions of revenge have been excited in the breasts of the Russian people.

Cheka (from the initialism ChK - Russian: ЧК), was the first of a succession of Soviet secret-police organizations. Established on December 5 (Old Style) 1917 by the Sovnarkom,[1] it came under the leadership of Felix Dzerzhinsky, a Polish aristocrat-turned-communist

In 1918 its name was changed, becoming All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution, Profiteering and Corruption.

A member of Cheka was called a chekist. Also, the term chekist often referred to Soviet secret police throughout the Soviet period, despite official name changes over time. In The Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsyn recalls that zeks in the labor camps used old chekist as a mark of special esteem for particularly experienced camp administrators

David R. Francis, United States ambassador in Russia, warned in a January 1918 dispatch to Washington: "The Bolshevik leaders here, most of whom are Jews and 90 percent of whom are returned exiles, care little for Russia or any other country but are internationalists and they are trying to start a worldwide social revolution."14

Index to the biographies and writings of members of the Party

that made the October 1917 Revolution in Russia.

that made the October 1917 Revolution in Russia.

The Netherlands' ambassador in Russia, Oudendyke, made much the same point a few months later: "Unless Bolshevism is nipped in the bud immediately, it is bound to spread in one form or another over Europe and the whole world as it is organized and worked by Jews who have no nationality, and whose one object is to destroy for their own ends the existing order of things."15

"The Bolshevik Revolution," declared a leading American Jewish community paper in 1920, "was largely the product of Jewish thinking, Jewish discontent, Jewish effort to reconstruct."16

As an expression of its radically anti-nationalist character, the fledgling Soviet government issued a decree a few months after taking power that made anti-Semitism a crime in Russia. The new Communist regime thus became the first in the world to severely punish all expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment.17 Soviet officials apparently regarded such measures as indispensable. Based on careful observation during a lengthy stay in Russia, American-Jewish scholar Frank Golder reported in 1925 that "because so many of the Soviet leaders are Jews anti-Semitism is gaining [in Russia], particularly in the army [and] among the old and new intelligentsia who are being crowded for positions by the sons of Israel."18

Historians' Views

Summing up the situation at that time, Israeli historian Louis Rapoport writes: 19

Immediately after the [Bolshevik] Revolution, many Jews were euphoric over their high representation in the new government. Lenin's first Politburo was dominated by men of Jewish origins.Under Lenin, Jews became involved in all aspects of the Revolution, including its dirtiest work. Despite the Communists' vows to eradicate anti-Semitism, it spread rapidly after the Revolution -- partly because of the prominence of so many Jews in the Soviet administration, as well as in the traumatic, inhuman Sovietization drives that followed. Historian Salo Baron has noted that an immensely disproportionate number of Jews joined the new Bolshevik secret police, the Cheka And many of those who fell afoul of the Cheka would be shot by Jewish investigators.The collective leadership that emerged in Lenin's dying days was headed by the Jew Zinoviev, a loquacious, mean-spirited, curly-haired Adonis whose vanity knew no bounds.

"Anyone who had the misfortune to fall into the hands of the Cheka," wrote Jewish historian Leonard Schapiro, "stood a very good chance of finding himself confronted with, and possibly shot by, a Jewish investigator."20 In Ukraine, "Jews made up nearly 80 percent of the rank-and-file Cheka agents," reports W. Bruce Lincoln, an American professor of Russian history.21 (Beginning as the Cheka, or Vecheka) the Soviet secret police was later known as the GPU, OGPU, NKVD, MVD and KGB.)

In light of all this, it should not be surprising that Yakov M. Yurovksy, the leader of the Bolshevik squad that carried out the murder of the Tsar and his family, was Jewish, as was Sverdlov, the Soviet chief who co-signed Lenin's execution order.22

Igor Shafarevich, a Russian mathematician of world stature, has sharply criticized the Jewish role in bringing down the Romanov monarchy and establishing Communist rule in his country. Shafarevich was a leading dissident during the final decades of Soviet rule. A prominent human rights activist, he was a founding member of the Committee on the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR.

In Russophobia, a book written ten years before the collapse of Communist rule, he noted that Jews were "amazingly" numerous among the personnel of the Bolshevik secret police. The characteristic Jewishness of the Bolshevik executioners, Shafarevich went on, is most conspicuous in the execution of Nicholas II:23

This ritual action symbolized the end of centuries of Russian history, so that it can be compared only to the execution of Charles I in England or Louis XVI in France. It would seem that representatives of an insignificant ethnic minority should keep as far as possible from this painful action, which would reverberate in all history. Yet what names do we meet? The execution was personally overseen by Yakov Yurovsky who shot the Tsar; the president of the local Soviet was Beloborodov (Vaisbart); the person responsible for the general administration in Ekaterinburg was Shaya Goloshchekin. To round out the picture, on the wall of the room where the execution took place was a distich from a poem by Heine (written in German) about King Balthazar, who offended Jehovah and was killed for the offense.

In his 1920 book, British veteran journalist Robert Wilton offered a similarly harsh assessment:24

The whole record of Bolshevism in Russia is indelibly impressed with the stamp of alien invasion. The murder of the Tsar, deliberately planned by the Jew Sverdlov (who came to Russia as a paid agent of Germany) and carried out by the Jews Goloshchekin, Syromolotov, Safarov, Voikov and Yurovsky, is the act not of the Russian people, but of this hostile invader.

In the struggle for power that followed Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin emerged victorious over his rivals, eventually succeeding in putting to death nearly every one of the most prominent early Bolsheviks leaders - including Trotsky, Zinoviev, Radek, and Kamenev. With the passage of time, and particularly after 1928, the Jewish role in the top leadership of the Soviet state and its Communist party diminished markedly.

Put To Death Without Trial

For a few months after taking power, Bolshevik leaders considered bringing "Nicholas Romanov" before a "Revolutionary Tribunal" that would publicize his "crimes against the people" before sentencing him to death. Historical precedent existed for this. Two European monarchs had lost their lives as a consequence of revolutionary upheaval: England's Charles I was beheaded in 1649, and France's Louis XVI was guillotined in 1793.

In these cases, the king was put to death after a lengthy public trial, during which he was allowed to present arguments in his defense. Nicholas II, though, was neither charged nor tried. He was secretly put to death - along with his family and staff -- in the dead of night, in an act that resembled more a gangster-style massacre than a formal execution.

Why did Lenin and Sverdlov abandon plans for a show trial of the former Tsar? In Wilton's view, Nicholas and his family were murdered because the Bolshevik rulers knew quite well that they lacked genuine popular support, and rightly feared that the Russian people would never approve killing the Tsar, regardless of pretexts and legalistic formalities.

For his part, Trotsky defended the massacre as a useful and even necesssary measure. He wrote:25

The decision [to kill the imperial family] was not only expedient but necessary. The severity of this punishment showed everyone that we would continue to fight on mercilessly, stopping at nothing. The execution of the Tsar's family was needed not only in order to frighten, horrify, and instill a sense of hopelessness in the enemy but also to shake up our own ranks, to show that there was no turning back, that ahead lay either total victory or total doom. This Lenin sensed well.

Historical Context

In the years leading up to the 1917 revolution, Jews were disproportionately represented in all of Russia's subversive leftist parties.26 Jewish hatred of the Tsarist regime had a basis in objective conditions. Of the leading European powers of the day, imperial Russia was the most institutionally conservative and anti-Jewish. For example, Jews were normally not permitted to reside outside a large area in the west of the Empire known as the "Pale of Settlement."27

However understandable, and perhaps even defensible, Jewish hostility toward the imperial regime may have been, the remarkable Jewish role in the vastly more despotic Soviet regime is less easy to justify. In a recently published book about the Jews in Russia during the 20th century, Russian-born Jewish writer Sonya Margolina goes so far as to call the Jewish role in supporting the Bolshevik regime the "historic sin of the Jews."28 She points, for example, to the prominent role of Jews as commandants of Soviet Gulag concentration and labor camps, and the role of Jewish Communists in the systematic destruction of Russian churches. Moreover, she goes on, "The Jews of the entire world supported Soviet power, and remained silent in the face of any criticism from the opposition."

In light of this record, Margolina offers a grim prediction:

In light of this record, Margolina offers a grim prediction:

The exaggeratedly enthusiastic participation of the Jewish Bolsheviks in the subjugation and destruction of Russia is a sin that will be avenged Soviet power will be equated with Jewish power, and the furious hatred against the Bolsheviks will become hatred against Jews.

If the past is any indication, it is unlikely that many Russians will seek the revenge that Margolina prophecies. Anyway, to blame "the Jews" for the horrors of Communism seems no more justifiable than to blame "white people" for Negro slavery, or "the Germans" for the Second World War or "the Holocaust."

Words of Grim Portent

Nicholas and his family are only the best known of countless victims of a regime that openly proclaimed its ruthless purpose. A few weeks after the Ekaterinburg massacre, the newspaper of the fledgling Red Army declared:29

Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies by the scores of hundreds, let them be thousands, let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritskii let there be floods of blood of the bourgeoisie -- more blood, as much as possible.

Grigori Zinoviev, speaking at a meeting of Communists in September 1918, effectively pronounced a death sentence on ten million human beings: "We must carry along with us 90 million out of the 100 million of Soviet Russia's inhabitants. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated."30

'The Twenty Million'

As it turned out, the Soviet toll in human lives and suffering proved to be much higher than Zinoviev's murderous rhetoric suggested. Rarely, if ever, has a regime taken the lives of so many of its own people.31

Citing newly-available Soviet KGB documents, historian Dmitri Volkogonov, head of a special Russian parliamentary commission, recently concluded that "from 1929 to 1952, 21.5 million [Soviet] people were repressed. Of these a third were shot, the rest sentenced to imprisonment, where many also died."32

Olga Shatunovskaya, a member of the Soviet Commission of Party Control, and head of a special commission during the 1960s appointed by premier Khrushchev, has similarly concluded: "From January 1, 1935 to June 22, 1941, 19,840,000 enemies of the people were arrested. Of these, seven million were shot in prison, and a majority of the others died in camp." These figures were also found in the papers of Politburo member Anastas Mikoyan.33

Robert Conquest, the distinguished specialist of Soviet history, recently summed up the grim record of Soviet "repression" of it own people:34

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the post-1934 death toll was well over ten million. To this should be added the victims of the 1930-1933 famine, the kulak deportations, and other anti-peasant campaigns, amounting to another ten million plus. The total is thus in the range of what the Russians now refer to as 'The Twenty Million'."

A few other scholars have given significantly higher estimates.35

The Tsarist Era in Retrospect

With the dramatic collapse of Soviet rule, many Russians are taking a new and more respectful look at their country's pre-Communist history, including the era of the last Romanov emperor. While the Soviets -- along with many in the West -- have stereotypically portrayed this era as little more than an age of arbitrary despotism, cruel suppression and mass poverty, the reality is rather different. While it is true that the power of the Tsar was absolute, that only a small minority had any significant political voice, and that the mass of the empire's citizens were peasants, it is worth noting that Russians during the reign of Nicholas II had freedom of press, religion, assembly and association, protection of private property, and free labor unions. Sworn enemies of the regime, such as Lenin, were treated with remarkable leniency.36

During the decades prior to the outbreak of the First World War, the Russian economy was booming. In fact, between 1890 and 1913, it was the fastest growing in the world. New rail lines were opened at an annual rate double that of the Soviet years. Between 1900 and 1913, iron production increased by 58 percent, while coal production more than doubled.37 Exported Russian grain fed all of Europe. Finally, the last decades of Tsarist Russia witnessed a magnificent flowering of cultural life.

Everything changed with the First World War, a catastrophe not only for Russia, but for the entire West.

Monarchist Sentiment

In spite of (or perhaps because of) the relentless official campaign during the entire Soviet era to stamp out every uncritical memory of the Romanovs and imperial Russia, a virtual cult of popular veneration for Nicholas II has been sweeping Russia in recent years.

People have been eagerly paying the equivalent of several hours' wages to purchase portraits of Nicholas from street vendors in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other Russian cities.

His portrait now hangs in countless Russian homes and apartments.

In late 1990, all 200,000 copies of a first printing of a 30-page pamphlet on the Romanovs quickly sold out.

Said one street vendor: "I personally sold four thousand copies in no time at all. It's like a nuclear explosion. People really want to know about their Tsar and his family." Grass roots pro-Tsarist and monarchist organizations have sprung up in many cities.

His portrait now hangs in countless Russian homes and apartments.

In late 1990, all 200,000 copies of a first printing of a 30-page pamphlet on the Romanovs quickly sold out.

Said one street vendor: "I personally sold four thousand copies in no time at all. It's like a nuclear explosion. People really want to know about their Tsar and his family." Grass roots pro-Tsarist and monarchist organizations have sprung up in many cities.

A public opinion poll conducted in 1990 found that three out of four Soviet citizens surveyed regard the killing of the Tsar and his family as a despicable crime.38 Many Russian Orthodox believers regard Nicholas as a martyr. The independent "Orthodox Church Abroad" canonized the imperial family in 1981, and the Moscow-based Russian Orthodox Church has been under popular pressure to take the same step, in spite of its long-standing reluctance to touch this official taboo. The Russian Orthodox Archbishop of Ekaterinburg announced plans in 1990 to build a grand church at the site of the killings. "The people loved Emperor Nicholas," he said. "His memory lives with the people, not as a saint but as someone executed without court verdict, unjustly, as a sufferer for his faith and for orthodoxy."39

On the 75th anniversary of the massacre (in July 1993), Russians recalled the life, death and legacy of their last Emperor. In Ekaterinburg, where a large white cross festooned with flowers now marks the spot where the family was killed, mourners wept as hymns were sung and prayers were said for the victims.40

Reflecting both popular sentiment and new social-political realities, the white, blue and red horizontal tricolor flag of Tsarist Russia was officially adopted in 1991, replacing the red Soviet banner. And in 1993, the imperial two-headed eagle was restored as the nation's official emblem, replacing the Soviet hammer and sickle. Cities that had been re-named to honor Communist figures -- such as Leningrad, Kuibyshev, Frunze, Kalinin, and Gorky -- have re-acquired their Tsarist-era names.

Ekaterinburg, which had been named Sverdlovsk by the Soviets in 1924 in honor of the Soviet-Jewish chief, in September 1991 restored its pre-Communist name, which honors Empress Catherine I.

Ekaterinburg, which had been named Sverdlovsk by the Soviets in 1924 in honor of the Soviet-Jewish chief, in September 1991 restored its pre-Communist name, which honors Empress Catherine I.

100 Years On: Bolshevik Scum Murdered

The Russian Tsar Nicholas II And His Family

Symbolic Meaning

In view of the millions that would be put to death by the Soviet rulers in the years to follow, the murder of the Romanov family might not seem of extraordinary importance. And yet, the event has deep symbolic meaning. In the apt words of Harvard University historian Richard Pipes:41

The manner in which the massacre was prepared and carried out, at first denied and then justified, has something uniquely odious about it, something that radically distinguishes it from previous acts of regicide and brands it as a prelude to twentieth-century mass murder.

Another historian, Ivor Benson, characterized the killing of the Romanov family as symbolic of the tragic fate of Russia and, indeed, of the entire West, in this century of unprecedented agony and conflict.

The murder of the Tsar and his family is all the more deplorable because, whatever his failings as a monarch, Nicholas II was, by all accounts, a personally decent, generous, humane and honorable man.

The Massacre's Place in History

The mass slaughter and chaos of the First World War, and the revolutionary upheavals that swept Europe in 1917-1918, brought an end not only to the ancient Romanov dynasty in Russia, but to an entire continental social order. Swept away as well was the Hohenzollern dynasty in Germany, with its stable constitutional monarchy, and the ancient Habsburg dynasty of Austria-Hungary with its multinational central European empire. Europe's leading states shared not only the same Christian and Western cultural foundations, but most of the continent's reigning monarchs were related by blood. England's King George was, through his mother, a first cousin of Tsar Nicholas, and, through his father, a first cousin of Empress Alexandra. Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm was a first cousin of the German-born Alexandra, and a distant cousin of Nicholas.

More than was the case with the monarchies of western Europe, Russia's Tsar personally symbolized his land and nation. Thus, the murder of the last emperor of a dynasty that had ruled Russia for three centuries not only symbolically presaged the Communist mass slaughter that would claim so many Russian lives in the decades that followed, but was symbolic of the Communist effort to kill the soul and spirit of Russia itself.

Notes

- Edvard Radzinksy, The Last Tsar (New York: Doubleday, 1992), pp. 327, 344-346.; Bill Keller, "Cult of the Last Czar," The New York Times, Nov. 21, 1990.

- From an April 1935 entry in "Trotsky's Diary in Exile." Quoted in: Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1990), pp. 770, 787.; Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra (New York: 1976), pp. 496-497.; E. Radzinksy, The Last Tsar (New York: Doubleday, 1992), pp. 325-326.; Ronald W. Clark, Lenin (New York: 1988), pp. 349-350.

- On Wilton and his career in Russia, see: Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976), pp. 141-142, 144-146, 151-152, 159, 162, 169, and, Anthony Summers and Tom Mangold, The File on the Tsar (New York: Harper and Row, 1976), pp. 102-104, 176.

- AP dispatch from Moscow, Toronto Star, Sept. 26, 1991, p. A2.; Similarly, a 1992 survey found that one-fourth of people in the republics of Belarus (White Russia) and Uzbekistan favored deporting all Jews to a special Jewish region in Russian Siberia. "Survey Finds Anti-Semitism on Rise in Ex-Soviet Lands," Los Angeles Times, June 12, 1992, p. A4.

- At the turn of the century, Jews made up 4.2 percent of the population of the Russian Empire. Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (New York: 1990), p. 55 (fn.).

By comparison, in the United States today, Jews make up less than three percent of the total population (according to the most authoritative estimates). - See individual entries in: H. Shukman, ed., The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution (Oxford: 1988), and in: G. Wigoder, ed., Dictionary of Jewish Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991).

The prominent Jewish role in Russia's pre-1914 revolutionary underground, and in the early Soviet regime, is likewise confirmed in: Stanley Rothman and S. Robert Lichter, Roots of Radicalism (New York: Oxford, 1982), pp. 92-94.

In 1918, the Bolshevik Party's Central Committee had 15 members. German scholar Herman Fehst -- citing published Soviet records -- reported in his useful 1934 study that of six of these 15 were Jews. Herman Fehst, Bolschewismus und Judentum: Das jüdische Element in der Führerschaft des Bolschewismus (Berlin: 1934), pp. 68-72.; Robert Wilton, though, reported that in 1918 the Central Committee of the Bolshevik party had twelve members, of whom nine were of Jewish origin and three were of Russian ancestry. R. Wilton, The Last Days of the Romanovs (IHR, 1993), p. 185. - After years of official suppression, this fact was acknowledged in 1991 in the Moscow weekly Ogonyok. See: Jewish Chronicle (London), July 16, 1991.; See also: Letter by L. Horwitz in The New York Times, Aug. 5, 1992, which cites information from the Russian journal "Native Land Archives."; "Lenin's Lineage?"'Jewish,' Claims Moscow News," Forward (New York City), Feb. 28, 1992, pp. 1, 3.; M. Checinski, Jerusalem Post (weekly international edition), Jan. 26, 1991, p. 9.

- Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1990), p. 352.

- Harrison E. Salisbury, Black Night, White Snow: Russia's Revolutions, 1905-1917 (Doubleday, 1978), p. 475.; William H. Chamberlin, The Russian Revolution (Princeton Univ. Press, 1987), vol. 1, pp. 291-292.; Herman Fehst, Bolschewismus und Judentum: Das jüdische Element in der Führerschaft des Bolschewismus (Berlin: 1934), pp. 42-43.; P. N. Pospelov, ed., Vladimir Ilyich Lenin: A Biography (Moscow: Progress, 1966), pp. 318-319.

This meeting was held on October 10 (old style, Julian calendar), and on October 23 (new style). The six Jews who took part were: Uritsky, Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Sverdlov and Soklonikov.

The Bolsheviks seized power in Petersburg on October 25 (old style) -- hence the reference to the "Great October Revolution" -- which is November 7 (new style). - William H. Chamberlin, The Russian Revolution (1987), vol. 1, p. 292.; H. E. Salisbury, Black Night, White Snow: Russia's Revolutions, 1905-1917 (1978), p. 475.

- W. H. Chamberlin, The Russian Revolution, vol. 1, pp. 274, 299, 302, 306.; Alan Moorehead, The Russian Revolution (New York: 1965), pp. 235, 238, 242, 243, 245.; H. Fehst, Bolschewismus und Judentum (Berlin: 1934), pp. 44, 45.

- H. E. Salisbury, Black Night, White Snow: Russia's Revolutions, 1905-1917 (1978), p. 479-480.; Dmitri Volkogonov, Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991), pp. 27-28, 32.; P. N. Pospelov, ed., Vladimir Ilyich Lenin: A Biography (Moscow: Progress, 1966), pp. 319-320.

- "Zionism versus Bolshevism: A struggle for the soul of the Jewish people," Illustrated Sunday Herald (London), February 8, 1920. Facsimile reprint in: William Grimstad, The Six Million Reconsidered (1979), p. 124. (At the time this essay was published, Churchill was serving as minister of war and air.)

- David R. Francis, Russia from the American Embassy (New York: 1921), p. 214.

- Foreign Relations of the United States -- 1918 -- Russia, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: 1931), pp. 678-679.

- American Hebrew (New York), Sept. 1920. Quoted in: Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot (Cambridge, Mass.: 1963), p. 268.

- C. Jacobson, "Jews in the USSR" in: American Review on the Soviet Union, August 1945, p. 52.; Avtandil Rukhadze, Jews in the USSR: Figures, Facts, Comment (Moscow: Novosti, 1978), pp. 10-11.

- T. Emmons and B. M. Patenaude, eds., War, Revolution and Peace in Russia: The Passages of Frank Golder, 1913-1927 (Stanford: Hoover Institution, 1992), pp. 320, 139, 317.

- Louis Rapoport, Stalin's War Against the Jews (New York: Free Press, 1990), pp. 30, 31, 37. See also pp. 43, 44, 45, 49, 50.

- Quoted in: Salo Baron, The Russian Jews Under Tsars and Soviets (New York: 1976), pp. 170, 392 (n. 4).

- The Atlantic, Sept. 1991, p. 14.;

In 1919, three-quarters of the Cheka staff in Kiev were Jews, who were careful to spare fellow Jews. By order, the Cheka took few Jewish hostages. R. Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), p. 824.; Israeli historian Louis Rapoport also confirms the dominant role played by Jews in the Soviet secret police throughout the 1920s and 1930s. L. Rapoport, Stalin's War Against the Jews (New York: 1990), pp. 30-31, 43-45, 49-50. - E. Radzinsky, The Last Tsar (1992), pp. 244, 303-304.; Bill Keller, "Cult of the Last Czar," The New York Times, Nov. 21, 1990.; See also: W. H. Chamberlin, The Russian Revolution, vol. 2, p. 90.

- Quoted in: The New Republic, Feb. 5, 1990, pp. 30 ff.; Because of the alleged anti-Semitism of Russophobia, in July 1992 Shafarevich was asked by the National Academy of Sciences (Washington, DC) to resign as an associate member of that prestigious body.

- R. Wilton, The Last Days of the Romanovs (1993), p. 148.

- Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), p. 787.; Robert K. Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra (New York: 1976), pp. 496-497.

- An article in a 1907 issue of the respected American journal National Geographic reported on the revolutionary situation brewing in Russia in the years before the First World War: " The revolutionary leaders nearly all belong to the Jewish race, and the most effective revolutionary agency is the Jewish Bund " W. E. Curtis, "The Revolution in Russia," The National Geographic Magazine, May 1907, pp. 313-314.

Piotr Stolypin, probably imperial Russia's greatest statesman, was murdered in 1911 by a Jewish assassin. In 1907, Jews made up about ten percent of Bolshevik party membership. In the Menshevik party, another faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, the Jewish proportion was twice as high. R. Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), p. 365.; See also: R. Wilton, The Last Days of the Romanovs (1993), pp. 185-186. - Martin Gilbert, Atlas of Jewish History (1977), pp. 71, 74.; In spite of the restrictive "Pale" policy, in 1897 about 315,000 Jews were living outside the Pale, most of them illegally. In 1900 more than 20,000 were living in the capital of St. Petersburg, and another 9,000 in Moscow.

- Sonja Margolina, Das Ende der Lügen: Russland und die Juden im 20. Jahrhundert (Berlin: 1992). Quoted in: "Ein ganz heisses Eisen angefasst," Deutsche National-Zeitung (Munich), July 21, 1992, p. 12.

- Krasnaia Gazetta ("Red Gazette"), September 1, 1918. Quoted in: Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), pp. 820, 912 (n. 88).

- Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (New York: 1990), p. 820.

- Contrary to what a number of western historians have for years suggested, Soviet terror and the Gulag camp system did not begin with Stalin. At the end of 1920, Soviet Russia already had 84 concentration camps with approximately 50,000 prisoners. By October 1923 the number had increased to 315 camps with 70,000 inmates. R. Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), p. 836.

- Cited by historian Robert Conquest in a review/ article in The New York Review of Books, Sept. 23, 1993, p. 27.

- The New York Review of Books, Sept. 23, 1993, p. 27.

- Review/article by Robert Conquest in The New York Review of Books, Sept. 23, 1993, p. 27.; In the "Great Terror" years of 1937-1938 alone, Conquest has calculated, approximately one million were shot by the Soviet secret police, and another two million perished in Soviet camps. R. Conquest, The Great Terror (New York: Oxford, 1990), pp. 485-486.;

Conquest has estimated that 13.5 to 14 million people perished in the collectivization ("dekulakization") campaign and forced famine of 1929-1933. R. Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow (New York: Oxford, 1986), pp. 301-307. - Russian professor Igor Bestuzhev-Lada, writing in a 1988 issue of the Moscow weekly Nedelya, suggested that during the Stalin era alone (1935-1953), as many as 50 million people were killed, condemned to camps from which they never emerged, or lost their lives as a direct result of the brutal "dekulakization" campaign against the peasantry. "Soviets admit Stalin killed 50 million," The Sunday Times, London, April 17, 1988.;

R. J. Rummel, a professor of political science at the University of Hawaii, has recently calculated that 61.9 million people were systematically killed by the Soviet Communist regime from 1917 to 1987. R. J. Rummel, Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917 (Transaction, 1990). - Because of his revolutionary activities, Lenin was sentenced in 1897 to three years exile in Siberia. During this period of "punishment," he got married, wrote some 30 works, made extensive use of a well-stocked local library, subscribed to numerous foreign periodicals, kept up a voluminous correspondence with supporters across Europe, and enjoyed numerous sport hunting and ice skating excursions, while all the time receiving a state stipend. See: Ronald W. Clark, Lenin (New York: 1988), pp. 42-57.; P. N. Pospelov, ed., Vladimir Ilyich Lenin: A Biography (Moscow: Progress, 1966), pp. 55-75.

- R. Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), pp. 187-188.;

- The Nation, June 24, 1991, p. 838.

- Bill Keller, "Cult of the Last Czar," The New York Times, Nov. 21, 1990.

- "Nostalgic for Nicholas, Russians Honor Their Last Czar," Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1993.; "Ceremony marks Russian czar's death," Orange County Register, July 17, 1993.

- R. Pipes, The Russian Revolution (1990), p. 787.

Source: Ihr.org

_____

How Rothschild, George V, & Wallstreet Murdered Czar Nicholas with Bolsheviks, & Stole all Russian Assets

1) They Murdered the Czar to steal all the gold, etc. of the richest man in world, all assets then sent to Rothschild/Rockefeller, Kuhn Loeb, etc. finance offices in London, Paris, New York City;

2) The Cold War was a complete Fraud so Wall Street---after they destroyed Russia, could control a thus destitute country;

3) And also so Defence Industries (heavily Rockefeller/Rothschild owned) could vastly profit from the vast funds spent by Federal Reserve with interest bearing currency---which, while owning the Federal Reserve, the govt/people must repay for a War Industry wholly unneeded.

see: murderingjane.com

greatgoldgrab.com

As Mullins states and seen essentially agreeable by Sutton, first thing is to arrest all directors of Federal and seize all its stolen assets and Profits.

_____

Execution of the Romanov family

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThe Russian Imperial Romanov family (Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Tsarina Alexandra and their five children:

Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei) and all those who chose to accompany them into imprisonment notably Eugene Botkin, Anna Demidova, Alexei Trupp and Ivan Kharitonov, according to the conclusion of the investigator Sokolov, were shot and bayoneted to death[1][2] in Yekaterinburg

on the night of 16–17 July 1918.[3]

According to the official state version in the USSR, former Tsar Nicholas Romanov, along with members of his family and retinue, was executed by firing squad, by order of the Ural Regional Soviet, due to the threat of the city being occupied by Whites (Czechoslovak Legion)[4][5].

By the assumption of a number of researchers, this was done according to instructions by Lenin, Yakov Sverdlov and Felix Dzerzhinsky. Their bodies were then taken to the Koptyaki forest where they were stripped and mutilated.[6][2]

Clockwise from top: The Romanov family, Ivan Kharitonov, Alexei Trupp, Anna Demidova, Eugene Botkin

In 1919, White Armyinvestigation (of Sokolov) failed to find the gravesite, concluding that the imperial family's remains had been cremated at the mineshaft called Ganina Yama, since evidence of fire was found.[7]. In 1979 and 2007, the remains of the bodies were found in two unmarkedgraves in a field called Porosenkov Log.[8]

on the night of 16–17 July 1918.[3]

According to the official state version in the USSR, former Tsar Nicholas Romanov, along with members of his family and retinue, was executed by firing squad, by order of the Ural Regional Soviet, due to the threat of the city being occupied by Whites (Czechoslovak Legion)[4][5].

By the assumption of a number of researchers, this was done according to instructions by Lenin, Yakov Sverdlov and Felix Dzerzhinsky. Their bodies were then taken to the Koptyaki forest where they were stripped and mutilated.[6][2]

Clockwise from top: The Romanov family, Ivan Kharitonov, Alexei Trupp, Anna Demidova, Eugene Botkin

In 1919, White Armyinvestigation (of Sokolov) failed to find the gravesite, concluding that the imperial family's remains had been cremated at the mineshaft called Ganina Yama, since evidence of fire was found.[7]. In 1979 and 2007, the remains of the bodies were found in two unmarkedgraves in a field called Porosenkov Log.[8]

Following the February Revolution, the Romanov family and their loyal servants were imprisoned in the Alexander Palace before being moved to Tobolsk and then Yekaterinburg, where they were killed, allegedly at the express command of Vladimir Lenin.[9] Despite being informed that "the entire family suffered the same fate as its head",[10] the Bolsheviks only announced Nicholas's death,[11][12] with the official press release that "Nicholas Romanov's wife and son have been sent to a secure place."[10] For over eight years,[13] the Soviet leadership maintained a systematic web of disinformation as to the fate of the family,[14] from claiming in September 1919 that they were murdered by left-wing revolutionaries[15] to denying outright in April 1922 that they were dead.[14]They acknowledged the murders in 1926 following the publication of an investigation by aWhite émigré, but maintained that the bodies were destroyed and that Lenin's Cabinetwas not responsible.[16] The Soviet cover-up of the murders fuelled rumours of survivors,[17] leading to the emergence of Romanov impostors that drew media attention away from Soviet Russia.[14] Discussion regarding the fate of the family was suppressed by Joseph Stalin from 1938.[18]

The burial site was discovered in 1979 by an amateur sleuth,[19] but the existence of the remains was not made public until 1989, during the glasnost period.[20] The identity of the remains was confirmed by forensic and DNA investigation. They were reburied in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in Saint Petersburg in 1998,[21] 80 years after they were killed, in a funeral that was not attended by key members of the Russian Orthodox Church, who disputed the authenticity of the remains.[22] A second, smaller grave containing the remains of two Romanov children missing from the larger grave was discovered by amateur archaeologists in 2007.[19] However, their remains are kept in a state repository pending further DNA tests.[23] In 2008, after considerable and protracted legal wrangling, the Russian Prosecutor General's office rehabilitated the Romanov family as "victims of political repressions".[24] A criminal case was opened by the post-Sovietgovernment in 1993, but nobody was prosecuted on the basis that the perpetrators were dead.[23]

Some historians attribute the order to the government in Moscow, specifically Sverdlov and Lenin who wished to prevent the rescue of the Imperial Family by the approaching Czechoslovak Legion (fighting with the White Army against the Bolsheviks) during the ongoing Russian Civil War.[25][26] This is supported by a passage in Leon Trotsky's diary.[27] An investigation led by Vladimir Solovyov concluded in 2011 that, despite the opening of state archives in the post-Soviet years, there is yet no written document found that indicates that either Lenin or Sverdlov instigated the orders; however, they did endorse the executions after they occurred.[28][29][30][31] Lenin had close control over the Romanovs although he ensured his name was not associated with their fate in any official documents.[32] President Boris Yeltsin described the killings as one of the most shameful pages in Russian history.[33][34]

Contents

Background

On 22 March 1917, Nicholas, no longer a monarch and addressed by the sentries as "Nicholas Romanov", was reunited with his family at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. He was placed under house arrest with his family by the Provisional Government, surrounded by guards and confined to their quarters.[35]

In August 1917, Alexander Kerensky's provisional government evacuated the Romanovs to Tobolsk, allegedly to protect them from the rising tide of revolution. There they lived in the former governor's mansion in considerable comfort. After the Bolsheviks came to power in October 1917, the conditions of their imprisonment grew stricter, and talk of putting Nicholas on trial grew more frequent. Nicholas was forbidden to wear epaulettes, and the sentries scrawled lewd drawings on the fence to offend his daughters. On 1 March 1918, the family was placed on soldier's rations, which meant parting with 10 devoted servants and giving up butter and coffee.[36]

As the Bolsheviks gathered strength, the government in April moved Nicholas, Alexandra, and their daughter Maria to Yekaterinburg under the direction of Vasily Yakovlev. Alexei, who had severe haemophilia, was too ill to accompany his parents and remained with his sisters Olga, Tatiana, and Anastasia, not leaving Tobolsk until May 1918. The family was imprisoned with a few remaining retainers in Yekaterinburg's Ipatiev House, which was designated The House of Special Purpose (Russian: Дом Особого Назначения).

As the Bolsheviks gathered strength, the government in April moved Nicholas, Alexandra, and their daughter Maria to Yekaterinburg under the direction of Vasily Yakovlev. Alexei, who had severe haemophilia, was too ill to accompany his parents and remained with his sisters Olga, Tatiana, and Anastasia, not leaving Tobolsk until May 1918. The family was imprisoned with a few remaining retainers in Yekaterinburg's Ipatiev House, which was designated The House of Special Purpose (Russian: Дом Особого Назначения).

The House of Special Purpose

The imperial family was kept in strict isolation at the Ipatiev House.[39] They were strictly forbidden to speak any language other than Russian.[40] They were not permitted access to their luggage, which was stored in an outhouse in the interior courtyard.[39] Their brownie cameras and photographic equipment were confiscated.[37] The servants were ordered to address the Romanovs only by their names andpatronymics.[41] The family was subjected to regular searches of their belongings, confiscation of their money for "safekeeping by the Ural Regional Soviet's treasurer",[42] and attempts to remove Alexandra's and her daughters' gold bracelets from their wrists.[43] The house was surrounded by a 4 metre (14 ft) high double palisade that obscured the streets from the house.[44] The initial fence enclosed the garden along Voznesensky Lane. On 5 June a second palisade was erected, higher and longer than the first, which completely enclosed the property.[45] One of the reasons for the construction of the latter was the discovery that onlookers outside could see Nicholas' legs over the palisade when he used the double swing in the garden.[46]

The windows in all the family's rooms were sealed shut and covered with newspapers (later painted withwhitewash on 15 May).[49] The family's only source of ventilation was a fortochka in the grand duchesses' bedroom, but peeking out of it was strictly forbidden; in May a sentry fired a shot at Anastasia when she peeked out.[50] After repeated requests, one of the two windows in the tsar and tsarina's corner bedroom was unsealed on 23 June 1918.[51] However, the guards were ordered to increase their surveillance accordingly and the prisoners were warned not to look out the window or attempt to signal anyone outside, on pain of being shot.[52] From this window, they could see only thespire of the Voznesensky Cathedral located across the road from the house.[52] An iron grille was installed on 11 July after Alexandra ignored repeated warnings from Yurovsky not to stand too close to the open window.[53]

The guard commandant and his senior aides had complete access at any time to all rooms occupied by the family.[54] The prisoners were required to ring a bell every time they wished to leave their rooms to use the bathroom and lavatory on the landing.[55] However, strict rationing of the water supply was enforced on the prisoners after the guards complained that it regularly ran out.[56] Recreation was only allowed twice daily in the garden for half an hour morning and afternoon. However, the prisoners were under strict instructions not to engage in conversation with any of the guards.[57] Rations were mostly tea and black bread for breakfast and cutlets or soup with meat for lunch; the prisoners were informed that "they were no longer permitted to live like tsars".[58] In mid-June, nuns from the Novo-Tikhvinsky Monastery also brought the family food on a daily basis, most of which was siphoned off on arrival by the captors.[58]

The family was not allowed visitors or to receive and send letters.[37] Princess Helen of Serbia visited the house in June but was refused entry at gunpoint by the guards,[59] while Dr Vladimir Derevenko's regular visits to treat Alexei were curtailed when Yurovsky became commandant. No excursions to Mass at the nearby church were permitted.[40] In early June, the family no longer received their daily newspapers.[37]

The family was not allowed visitors or to receive and send letters.[37] Princess Helen of Serbia visited the house in June but was refused entry at gunpoint by the guards,[59] while Dr Vladimir Derevenko's regular visits to treat Alexei were curtailed when Yurovsky became commandant. No excursions to Mass at the nearby church were permitted.[40] In early June, the family no longer received their daily newspapers.[37]

To maintain a sense of normality, the Bolsheviks assured the Romanovs on 13 July 1918 that two of their loyal servants,Klementy Nagorny (Alexei's sailor nanny)[61] and Ivan Sednev(OTMA's footman; Leonid Sednev's uncle),[62] "had been sent out of this government" (i.e. out of the jurisdiction of Yekaterinburg and Perm province). However, both men were already dead: after the Bolsheviks had removed them from the Ipatiev House in May, they had been shot by the Cheka with a group of other hostages on 6 July, in reprisal for the death of Ivan Malyshev, a local Bolshevik hero, killed by the Whites.[63] On 14 July, a priest and deacon conducted a liturgy for the Romanovs.[64] The following morning, four housemaids were hired to wash the floors of the Popov House and Ipatiev House; they were the last civilians to see the family alive. On both occasions, they were under strict instructions not to engage in conversation of any kind with the family.[65] Yurovsky always kept watch during the liturgy and while the housemaids were cleaning the bedrooms with the family.[66]

The 16 men of the internal guard slept in the basement, hallway and commandant's office during shifts. The external guard led by Pavel Medvedev numbered 56 and were accommodated in the Popov House opposite.[54] The guards were allowed to bring in women for sex and drinking sessions in the Popov House and basement rooms of the Ipatiev House.[66]

There were four machine gun emplacements: one in the bell tower of the Voznesensky Cathedral aimed toward the house; a second in the basement window of the Ipatiev House facing the street; a third monitored the balcony overlooking the garden at the back of the house;[52] and a fourth in the attic overlooking the intersection, directly above the tsar and tsarina's bedroom.[47] There were ten guard posts in and around the Ipatiev House, and the exterior was patrolled twice hourly day and night.[50] In early May, the guards deprived the prisoners of the piano in the dining room and moved it to the commandant's office located next door to the Romanovs' bedrooms. Here they took pleasure in humiliating them in the evenings by singing Russian revolutionary songs while drinking and smoking.[39] They also listened to the Romanovs' gramophone records on the confiscated phonograph.[39] The lavatory on the landing was also used by the guards who scribbled political slogans and crude graffiti on the walls.[39] The number of Ipatiev House guards totaled 300 when the imperial family was killed.[67]

There were four machine gun emplacements: one in the bell tower of the Voznesensky Cathedral aimed toward the house; a second in the basement window of the Ipatiev House facing the street; a third monitored the balcony overlooking the garden at the back of the house;[52] and a fourth in the attic overlooking the intersection, directly above the tsar and tsarina's bedroom.[47] There were ten guard posts in and around the Ipatiev House, and the exterior was patrolled twice hourly day and night.[50] In early May, the guards deprived the prisoners of the piano in the dining room and moved it to the commandant's office located next door to the Romanovs' bedrooms. Here they took pleasure in humiliating them in the evenings by singing Russian revolutionary songs while drinking and smoking.[39] They also listened to the Romanovs' gramophone records on the confiscated phonograph.[39] The lavatory on the landing was also used by the guards who scribbled political slogans and crude graffiti on the walls.[39] The number of Ipatiev House guards totaled 300 when the imperial family was killed.[67]

When Yurovsky replaced Aleksandr Avdeev as commandant on 4 July,[68] he moved the old internal guard members to the Popov House. The senior aides were retained but were designated to guard the hallway area and no longer had access to the Romanovs' rooms, a privilege granted only to Yurovsky's men. Replacements were chosen by the local Cheka from the volunteer battalions of the Verkh-Isetsk factory at Yurovsky's request. He wanted dedicated Bolsheviks who could be relied on to do whatever was asked of them. They were hired on the understanding that they would be prepared, if necessary, to kill the tsar, about which they were sworn to secrecy. Nothing at that stage was said about killing the family or servants. To prevent a repetition of the fraternization that had occurred under Avdeev, Yurovsky chose mainly foreigners. Nicholas noted in his diary on 8 July that "new Latvians are standing guard", describing them as Letts - a term commonly used in Russia to define someone of European, non-Russian origin. The leader of the new guards was led by Adolf Lepa, a Lithuanian.[69]

The Romanovs were being held by the Red Army in Yekaterinburg, since Bolsheviks initially wanted to put them on trial. As the civil war continued and the White Army (a loose alliance of anti-Communist forces) was threatening to capture the city, the fear was that the Romanovs would fall into White hands. This was unacceptable to the Bolsheviks for two reasons: first, the tsar or any of his family members could provide a beacon to rally support to the White cause; second, the tsar, or any of his family members if the tsar were dead, would be considered the legitimate ruler of Russia by the other European nations. This would have meant the ability to negotiate for greater foreign intervention on behalf of the Whites. Soon after the family was executed, the city fell to the White Army. In mid-July 1918, forces of the Czechoslovak Legion were closing on Yekaterinburg, to protect the Trans-Siberian Railway, of which they had control. According to historian David Bullock, the Bolsheviks, falsely believing that the Czechoslovaks were on a mission to rescue the family, panicked and executed their wards. The Legions arrived less than a week later and on 25 July captured the city.[70]

During the imperial family's imprisonment in late June, Pyotr Voykov and Alexander Beloborodov, president of the Ural Regional Soviet,[71]directed the smuggling of letters written in French to the Ipatiev House claiming to be a monarchist officer seeking to rescue them, composed at the behest of the Cheka.[72] These fabricated letters, along with the Romanov responses to them (written on either blank spaces or the envelopes),[73] provided the Central Executive Committee (CEC) in Moscow with further justification to 'liquidate' the imperial family.[74] Yurovsky later observed that by responding to the faked letters, Nicholas "had fallen into a hasty plan by us to trap him".[72] On 13 July, across the road from the Ipatiev House, a demonstration of Red Army soldiers, Socialist Revolutionaries, and anarchists was staged on Voznesensky Square, demanding the dismissal of the Yekaterinburg Soviet and the transfer of control of the city to them. This rebellion was violently suppressed by a detachment of Red Guards led by Peter Ermakov, which opened fire on the protesters, all within earshot of the tsar and tsarina's bedroom window. The authorities exploited the incident as a monarchist-led rebellion that threatened the security of the captives at the Ipatiev House.[75]

Planning for the execution

The Ural Regional Soviet agreed in a meeting on 29 June that the Romanov family should be executed. Filipp Goloshchyokin arrived in Moscow on 3 July with a message insisting on the Tsar's execution.[76] Only seven of the 23 members of the Central Executive Committee were in attendance, three of whom were Lenin, Sverdlov and Felix Dzerzhinsky.[71] It was agreed that the presidium of the Ural Regional Soviet should organize the practical details for the family's execution and decide the precise day on which it would take place when the military situation dictated it, contacting Moscow for final approval.[77]

The killing of the Tsar's wife and children was also discussed but had to be kept a state secret to avoid any political repercussions; German ambassador Wilhelm von Mirbach made repeated enquiries to the Bolsheviks concerning the family's well-being.[78] Another diplomat, British consul Thomas Preston, who lived near the Ipatiev House, was often pressured by Pierre Gilliard, Sydney Gibbes and Prince Vasily Dolgorukov to help the Romanovs,[59] the latter smuggling notes from his prison cell before he too was murdered by Grigory Nikulin, Yurovsky's assistant.[79] However, Preston's requests to be granted access to the family were consistently rejected.[80] As Trotsky would later explain, "The Tsar's family was a victim of the principle that form the very axis of monarchy: dynastic inheritance", for which their deaths were a necessity.[81] Goloshchyokin reported back to Yekaterinburg on 12 July with a summary of his discussion about the Romanovs with Moscow,[71] along with instructions that nothing relating to their deaths should be directly communicated to Lenin.[82]

On 14 July, Yurovsky was finalizing the disposal site and how to destroy as much evidence as possible at the same time.[83] He was frequently in consultation with Peter Ermakov, who was in charge of the disposal squad and claimed to know the outlying countryside, to which Yurovsky placed his trust in him.[84] Yurovsky wanted to gather the family and servants in a closely confined space from which they could not escape. The basement room chosen for this purpose had a barred window which was nailed shut to muffle the sound of shooting and in case of any screaming.[85] Shooting and stabbing them at night while they slept or killing them in the forest and then dumping them into the Iset pond with lumps of metal weighted to their bodies were ruled out.[86] Yurovsky's plan was to perform an efficient execution of all 11 prisoners simultaneously, though he also took into account that he would have to prevent those involved from raping the women or searching the bodies for jewels.[86] Having previously seized some jewellery, he suspected more was hidden in their clothes;[42] the bodies were stripped naked in order to obtain the rest (this, along with the mutilations were aimed at preventing investigators from identifying them).[6]

On 16 July, Yurovsky was informed by the Ural Soviets that Red Army contingents were retreating in all directions and the executions could not be delayed any longer. A coded telegram seeking final approval was sent by Goloshchyokin and Georgy Safarov at around 6:00pm to Lenin in Moscow.[87] There is no documentary record of an answer from Moscow, although Yurovsky insisted that an order from the CEC to go ahead had been passed on to him by Goloshchyokin at around 7:00pm.[88] This was consistent with a former Kremlin guard, Aleksey Akimov, who in the late 1960s claimed that Sverdlov personally instructed him to take a telegram to the telegraph office confirming the CEC's approval of the 'trial' (code for execution), but with strict instructions that both the written form and ticker tape should be brought back by him immediately after it had been sent.[88] At 8:00pm, Yurovsky sent his chauffeur to acquire a truck for transporting the bodies, bringing with it rolls of canvas to wrap them in. The intention was to park it as close to the basement entrance as possible, with its engine running to mask the noise of gunshots.[89]Yurovsky and Pavel Medvedev collected 14 handguns to use that night, comprising two Browning pistols (one M1900 and one M1906), two ColtM1911 pistols, two Mauser C96s, one Smith & Wesson and seven Belgian-made Nagants. The Nagant operated on old black gunpowder which produced a good deal of smoke and fumes; smokeless powder was only just being phased in.[90]

In the commandant's office, Yurovsky assigned victims to each killer before distributing the handguns. He took a Mauser and Colt while Ermakov armed himself with three Nagants, one Mauser and a bayonet; he was the only one assigned to kill two prisoners, Alexandra and Botkin. Yurovsky instructed his men to "shoot straight at the heart to avoid an excessive quantity of blood and get it over quickly."[91] At least two of the Letts, an Austro-Hungarian prisoner of war named Andras Verhas and Adolf Lepa, himself in charge of the Lett contingent, refused to shoot the women. Yurovsky sent them to the Popov House for failing "at that important moment in their revolutionary duty".[92] Neither Yurovsky nor any of the killers went into the logistics of how to efficiently destroy eleven bodies.[82] He was under pressure of ensuring that no remains would later be found by monarchists who would exploit them to rally anti-communist support.[93]

Execution

While the Romanovs were having dinner on 16 July 1918, Yurovsky entered the sitting room and informed them that the kitchen boy Leonid Sednev was leaving to meet his uncle Ivan Sednev, who had returned to the city asking to see him; Ivan had already been shot by the Cheka.[94] The family was very upset as Leonid was Alexei's only playmate and he was the fifth member of the imperial entourage to be taken from them, but they were assured by Yurovsky that he would be back soon. Alexandra did not trust him, writing in her final diary entry just hours before her death, "whether its [sic] true & we shall see the boy back again!" Leonid was in fact kept in the Popov House that night.[89] Yurovsky saw no reason to kill him and wanted him removed before the execution took place.[87]

Around midnight on 17 July, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of The House of Special Purpose, ordered the Romanovs' physician, Dr. Eugene Botkin, to awaken the sleeping family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Yekaterinburg.[95] The Romanovs were then ordered into a 6 m × 5 m (20 ft × 16 ft) semi-basement room. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat.[96] Yurovsky's assistant Grigory Nikulin remarked to him that the "heir wanted to die in a chair.[97] Very well then, let him have one."[85] The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given to him by the Ural Executive Committee:

Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said "What? What?"[99] Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised. The Empress and Grand Duchess Olga, according to a guard's reminiscence, had tried to bless themselves, but failed amid the shooting. Yurovsky reportedly raised his Colt gun at Nicholas's torso and fired; Nicholas fell dead, pierced with at least three bullets in his upper chest. The intoxicated Peter Ermakov, the military commissar for Verkh-Isetsk, shot and killed Alexandra with a bullet wound to the head. He then shot at Maria, who ran for the double doors, hitting her in the thigh.[100] The remaining executioners shot chaotically and over each other's shoulders until the room was so filled with smoke and dust that no one could see anything at all in the darkness nor hear any commands amid the noise.

Alexey Kabanov, who ran out onto the street to check the noise levels, heard dogs barking from the Romanovs' quarters and the sound of gunshots loud and clear despite the noise from the Fiat's engine. Kabanov then hurried downstairs and told the men to stop firing and kill the family and their dogs with their gun butts and bayonets.[101] Within minutes, Yurovsky was forced to stop the shooting because of the caustic smoke of burned gunpowder, dust from the plaster ceiling caused by the reverberation of bullets, and the deafening gunshots. When they stopped, the doors were then opened to scatter the smoke.[99] While waiting for the smoke to abate, the killers could hear moans and whimpers inside the room.[102] As it cleared, it became evident that although several of the family's retainers had been killed, all of the Imperial children were alive and furthermore, only Maria was even injured.[99][103]

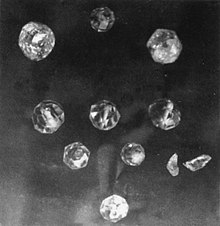

The noise of the guns had been heard by households all around, and had awakened many people. The executioners were ordered to proceed with their bayonets, a technique which proved ineffective and meant that the children had to be dispatched by still more gunshots, this time aimed more precisely at their heads. The Tsarevich was the first of the children to be executed. Yurovsky watched in disbelief as Nikulin spent an entire magazine from his Browning gun on Alexei, who was still seated transfixed in his chair; he also had jewels sewn into his undergarment and forage cap.[104] Ermakov shot and stabbed him, and when he failed, Yurovsky shoved him aside and killed the boy with a gunshot to the head.[100]The last to die were Tatiana, Anastasia, and Maria, who were carrying a few pounds (over 1.3 kilograms) of diamonds sewn into their clothing, which had given them a degree of protection from the firing.[105]However, they were speared with bayonets as well. Olga sustained a gunshot wound to the head. Maria and Anastasia were said to have crouched up against a wall covering their heads in terror until they were shot down. Yurovsky himself killed Tatiana and Alexei. Tatiana died from a single bullet through the back of her head.[106] Alexei received two bullets to the head, right behind the ear.[107] Anna Demidova, Alexandra's maid, survived the initial onslaught but was quickly stabbed to death against the back wall while trying to defend herself with a small pillow which she had carried that was filled with precious gems and jewels.[108] While the bodies were being placed on stretchers, one of the girls cried out and covered her face with her arm.[109] Ermakov grabbed Alexander Strekotin's rifle and bayoneted her in the chest,[109] but when it failed to penetrate he pulled out his revolver and shot her in the head.[110][111]

While Yurovsky was checking the victims for pulses, Ermakov went back and forth in the room, flailing the bodies with his bayonet. The execution lasted about 20 minutes, Yurovsky later admitting to Nikulin's "poor mastery of his weapon and inevitable nerves".[112] Future investigations calculated that a possible 70 bullets were fired, roughly seven bullets per shooter, of which 57 were found in the basement and at all three subsequent gravesites.[101] Some of Pavel Medvedev's stretcher bearers began frisking the bodies for valuables. Yurovsky saw this and demanded that they surrender any looted items or be shot. The attempted looting, coupled with Ermakov's incompetence and drunken state, convinced Yurovsky to oversee the disposal of the bodies himself.[111] Only Alexei's spaniel, Joy, survived to be rescued by a British officer of the Allied Intervention Force,[113] living out his final days in Windsor, Berkshire.[114]

Alexandre Beloborodov sent a coded telegram to Lenin's secretary, Nikolai Gorbunov. It was found by White investigator Nikolai Sokolov and reads:[115]

Aleksandr Lisitsyn of the Cheka, an essential witness on behalf of Moscow, was designated to promptly dispatch to Sverdlov soon after the executions of Nicholas and Alexandra's politically valuable diaries and letters, which would be published in Russia as soon as possible.[117]Beloborodov and Nikulin oversaw the ransacking of the Romanov quarters, seizing all the family's personal items, the most valuable piled up in Yurovsky's office whilst things considered inconsequential and of no value were stuffed into the stoves and burned. Everything was packed into the Romanovs' own trunks for dispatch to Moscow under escort by commissars.[118] On 19 July, the Bolsheviks nationalized all confiscated Romanov properties,[63] the same day Sverdlov announced the tsar's execution to the Council of People's Commissars.[119]

Disposal

The bodies of the Romanovs and their servants were loaded onto a Fiat truck equipped with a 60-hp engine,[111] with a cargo area 6 × 10 feet in size.[109] Heavily laden, the vehicle struggled for nine miles on boggy road to reach the Koptyaki forest. Yurovsky was furious when he discovered that the drunken Ermakov had brought only one shovel for the burial.[120] About half a mile further on, near crossing no. 185 on the line serving the Verkh-Isetsk works, 25 men working for Ermakov were waiting with horses and light carts. These men were all intoxicated and they were outraged that the prisoners were not brought to them alive. They expected to be part of the lynch mob[121] and were hoping to abuse the women before killing them.[122] Yurovsky maintained control of the situation with great difficulty, eventually getting Ermakov's men to shift some of the bodies from the truck onto the carts.[121] A few of Ermakov's men pawed the female bodies for diamonds hidden in their undergarments, two of whom lifted up Alexandra's skirt and fingered her genitals.[122][121] Yurovsky ordered them at gunpoint to back off, dismissing the two who had groped the tsarina's corpse and any others he had caught looting.[122] One of the men sniggered that he could "die in peace",[121] having touched the "royal cunt".[122]

The truck was bogged down in an area of marshy ground near the Gorno-Uralsk railway line, during which all the bodies were unloaded onto carts and taken to the disposal site.[121] The sun was up by the time the carts came within sight of the disused mine, which was a large clearing at a place called the 'Four Brothers'.[123] Yurovsky's men first gobbled on hardboiled eggs supplied by the local nuns (food that was meant for the imperial family), while the remainder of Ermakov's men were ordered back to the city as Yurovsky did not trust them and was displeased with their drunkenness.[6]

Yurovsky and five other men laid out the bodies on the grass and undressed them, the clothes piled up and burned while Yurovsky took inventory of their jewellery. Only Maria's undergarments contained no jewels, which to Yurovsky was proof that the family had ceased to trust her ever since she became too friendly with one of the guards back in May.[6][124]

Once the bodies were "completely naked" they were dumped into a mineshaft and sprinkled with sulphuric acid to disfigure them beyond recognition. Only then did Yurovsky discover that the pit was less than 3 metres (9 feet) deep and the muddy water below did not fully submerge the corpses as he had expected.

He unsuccessfully tried to collapse the mine with hand grenades, after which his men covered it with loose earth and branches.[125] Yurovsky left three men to guard the site while he returned to Yekaterinburg with a bag filled with 18 lb of looted diamonds, to report back to Beloborodov and Goloshchyokin. It was decided that the pit was too shallow.[126]

Once the bodies were "completely naked" they were dumped into a mineshaft and sprinkled with sulphuric acid to disfigure them beyond recognition. Only then did Yurovsky discover that the pit was less than 3 metres (9 feet) deep and the muddy water below did not fully submerge the corpses as he had expected.

He unsuccessfully tried to collapse the mine with hand grenades, after which his men covered it with loose earth and branches.[125] Yurovsky left three men to guard the site while he returned to Yekaterinburg with a bag filled with 18 lb of looted diamonds, to report back to Beloborodov and Goloshchyokin. It was decided that the pit was too shallow.[126]

Sergey Chutskaev of the local Soviet told Yurovsky of some deeper copper mines west of Yekaterinburg, the area remote and swampy and a grave there less likely to be discovered.[82] He inspected the site on the evening of 17 July and reported back to the Cheka at the Amerikanskaya Hotel. He ordered additional trucks to be sent out to Koptyaki whilst assigning Pyotr Voykov to obtain barrels of petrol, kerosene and sulphuric acid, and plenty of dry firewood. Yurovsky also seized several horse-drawn carts to be used in the removal of the bodies to the new site.[127] Yurovsky and Goloshchyokin, along with several Cheka agents, returned to the mineshaft at about 4:00am on the morning of 18 July.

The sodden corpses were hauled out one by one using ropes tied to their mangled limbs and laid under a tarpaulin.[126] Yurovsky, worried that he might not have enough time to take the bodies to the deeper mine, ordered his men to dig another burial pit then and there, but the ground was too hard. He returned to the Amerikanskaya Hotel to confer with the Cheka. He seized a truck which he had loaded with blocks of concrete for attaching to the bodies before submerging them in the new mineshaft. A second truck carried a detachment of Cheka agents to help move the bodies. Yurovsky returned to the forest at 10:00pm on 18 July. The bodies were again loaded onto the Fiat truck, which by then had been extricated from the mud.[128]

The sodden corpses were hauled out one by one using ropes tied to their mangled limbs and laid under a tarpaulin.[126] Yurovsky, worried that he might not have enough time to take the bodies to the deeper mine, ordered his men to dig another burial pit then and there, but the ground was too hard. He returned to the Amerikanskaya Hotel to confer with the Cheka. He seized a truck which he had loaded with blocks of concrete for attaching to the bodies before submerging them in the new mineshaft. A second truck carried a detachment of Cheka agents to help move the bodies. Yurovsky returned to the forest at 10:00pm on 18 July. The bodies were again loaded onto the Fiat truck, which by then had been extricated from the mud.[128]