- The Terrible Tragedy that Befell the People of Our Golden City

- The Metropolis of the Golden Gate, and the Death and Ruin Dealt Many Adjacent Cities and Surrounding Country.

- Destroying Earthquake Comes Without Warning, in the Early Hours of the Morning.

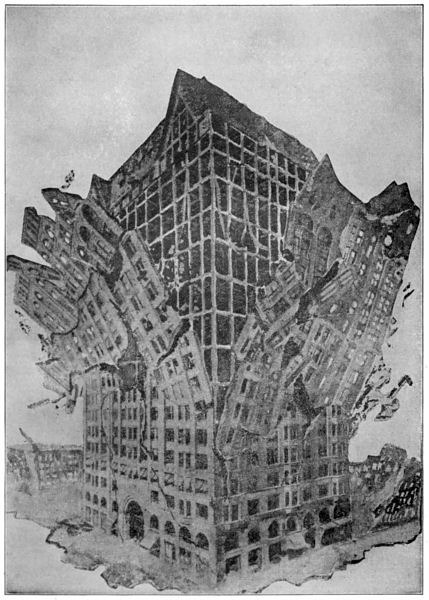

- Immense Structures Topple and Crumble.

- Great Leland Stanford University Succumbs.

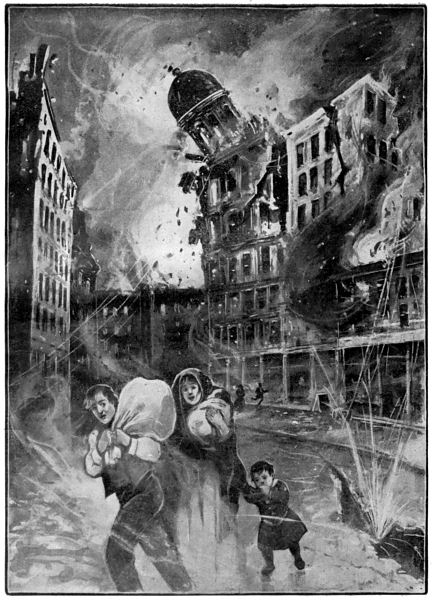

- Water Mains Demolished and Fire Completes Devastation.

- Fighting Fire With Dynamite.

- Thousands Killed, Maimed, or Unaccounted For.

- Tens of Thousands Without Food or Shelter; Martial Law Declared.

- Property Loss Hundreds of Millions.

- Appalling Stories by Eye Witnesses and Survivors.

- The Disaster as Viewed by Scientists, etc.

COMPLETE STORY OF THE

|

SCENES OF DEATH AND TERROR

|

Thousands Killed, Maimed, or Unaccounted For; Tens of Thousands Without Food

or Shelter; Martial Law Declared; Millions Donated for Relief; Congress Makes an Appropriation; Sympathetic Citizens Throughout the Land Untie Their Purse-Strings to Aid the Suffering and Destitute; Property Loss Hundreds of Millions; Appalling Stories by Eye Witnesses and Survivors; The Disaster as Viewed by Scientists, etc. |

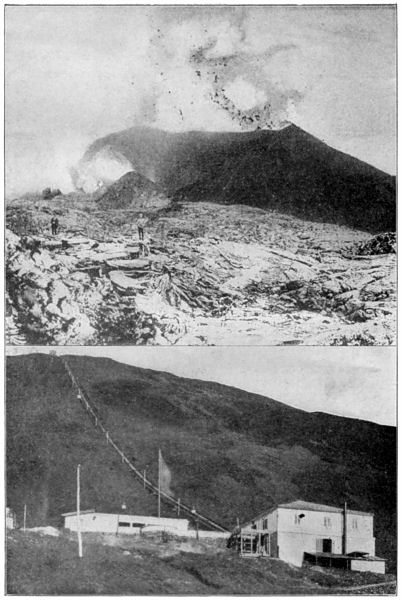

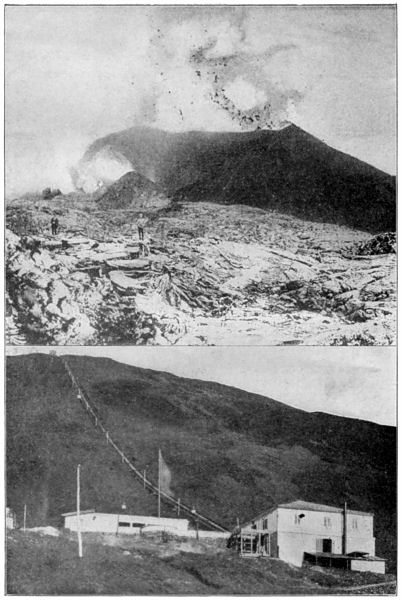

Comprising Also a Vivid Portrayal of the Recent Death-Dealing

ERUPTION OF MT. VESUVIUS

BY RICHARD LINTHICUM

of the Editorial Staff of the Chicago Chronicle. |

Together with twelve descriptive chapters giving a graphic and detailed account of the most interesting

and historic disasters of the past from ancient times to the present day.

BY TRUMBULL WHITE

Historian, Traveler and Geographer.

Profusely Illustrated with Photographic Scenes of the Great Disasters and Views

of the Devastated Cities and Their People. |

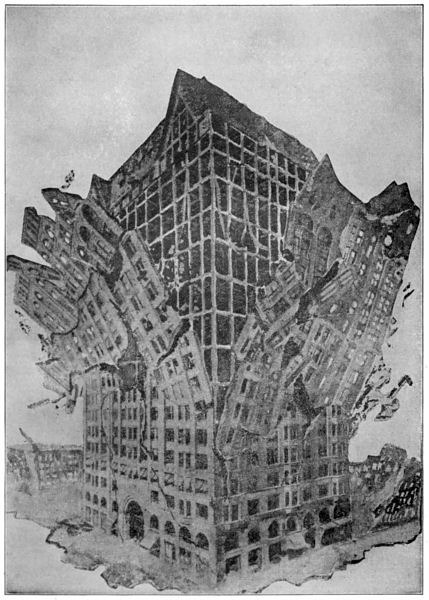

THE AWFUL HORROR OF AN EARTHQUAKE.

Lives, homes and property lost in a few seconds.

CHAPTER XVII.

MISCELLANEOUS FACTS AND INCIDENTS.

Many Babies Born in Refuge Camps—Expressions of Sympathy from Foreign Nations—San Francisco’s Famous Restaurants—Plight of Newspaper and Telegraph Offices.

IN the refugee camps a number of babies were born under the most distressing and pathetic circumstances, the mothers in many cases being unattended by either husbands or relatives. In Golden Gate Park alone fifteen babies were born in one night, it was reported. The excitement and agony of the situation brought the little ones prematurely into the world. And equally remarkable was the fact that when all danger was over all of the mothers and the children of the catastrophe were reported to have withstood the untoward conditions and continued to improve and grow strong as if the conditions which surrounded them had been normal. This, undoubtedly, was in great part due to the care and kindness of the physicians and surgeons in the camps whose efforts were untiring and self-sacrificing for all who had been so suddenly surrendered to their care.

In an express wagon bumping over the brick piles and broken streets was a mother who gave birth to triplets in the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park a week later. All the triplets were living and apparently doing well. In this narrow park strip where the triplets were born fifteen other babies came into the world on the same fateful night, and, strange as it seems, every one of the mothers and every one of the infants had been reported as doing well.

[Pg 215]The following night thirteen more babies were born in the park Panhandle, and these, so far as the reports show, fared as well as those born the first night. In fact, the doctors and nurses reported that there had been no fatality among the earthquake babies or their unfortunate mothers. One trained nurse who accompanied a prominent doctor on his rounds the first night after the shock attended eight cases in which both mothers and children thrived. One baby was born in a wheelbarrow as the mother was being trundled to the park by her husband.

Expressions of sympathy and condolence on account of the great disaster were sent to the President of the United States from all over the world. Among the messages received within about 24 hours after the catastrophe were the following:

From the President of Guatemala—I am deeply grieved by the catastrophe at San Francisco. The president of Guatemala sends to the people of the United States through your eminence his expression of the most sincere grief, with the confidence that in such a lamentable misfortune the indomitable spirit of your people will newly manifest itself—that spirit which, if great in prosperity, is equally great in time of trial.

President of Mexico—Will your excellency be so kind as to accept the expression of my profound and deep sympathy with the American people on account of the disaster at San Francisco, which has so affected the American people.

President of Brazil—I do myself the honor of sending to you the expression of the profound grief with which the government and people of the United States of Brazil have read the news of the great misfortune which has occurred at San Francisco.

Emperor of Japan—With assurances of the deepest and heartiest sympathy for the sufferers by the terrible earthquake.

King Leopold of Belgium—I must express to you the deep sympathy which I feel in the mourning which the terrible disaster at San Francisco is causing the whole American people.

[Pg 216]President of Cuba—In the name of the government and people of Cuba, I assure you of the deep grief and sympathy with which they have heard of the great misfortune which has overtaken San Francisco.

Kirkpatrick, acting premier of New Zealand—South Australia deplores the appalling disaster which has befallen the state of California and extends heartfelt sympathy to sufferers.

Viceroy of India—My deepest sympathy with you and people of United States in terrible catastrophe at San Francisco.

Governor Talbot of Victoria, Australia—On behalf of the people of Victoria, I beg to offer our heartfelt sympathy with the United States on the terrible calamity at San Francisco.

President of Switzerland—The federal council is profoundly affected by the terrible catastrophe which has visited San Francisco and other California cities, and I beg you to receive the sincere expressions of its regret and the sympathy of the Swiss people as a whole, who join in the mourning of a sister republic.

Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria—I beg to assure you, Mr. President, of my most sincere sympathy with your land in its sorrow because of the terrible earthquake at San Francisco, and I beg to offer you personally, Mr. President, my heartfelt condolences.

Prince Henry of Prussia—Remembering American hospitality, which is still so fresh in my memory, I hereby wish to express my deepest sympathy on behalf of the terrible catastrophe which has befallen the thriving city of San Francisco and which has destroyed so many valuable lives therein. Still hope that news is greatly exaggerated.

Premier Bent of South Wales—New South Wales and Victoria sympathize with California suffering disaster.

Count Witte—The Russian members of the Portsmouth conference, profoundly moved by the sad tidings of the calamity that has befallen the American people, whose hospitality they recently enjoyed, beg your excellency to accept and to transmit to citizens [Pg 217]of United States the expression of their profound and heartfelt sympathy.

The cathedral of San Francisco with the residences attached, together with the residence of the archbishop, were saved. Sacred Heart College and Mercy Hospital, together with the various schools attached, were destroyed.

The churches damaged by the earthquake are:

St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo park.

St. James’ church.

St. Bridget’s church.

St. Dominick’s church.

Church of the Holy Cross.

St. Patrick’s church at San Jose.

Those destroyed by fire were:

Churches of SS. Ignatius, Boniface, Joseph, Patrick, Brendan, Rose, Francis, Mission Dolores, French church, Slavonian church and the old Cathedral of St. Mary’s.

The Custom House with its records was saved. It was in one of the little islands which the fire passed by. All the city records which were in the vaults of the city hall were saved. The city hall fell, but the ruins did not burn. By this bit of luck the city escapes great confusion in property claims and adjustments.

Millet’s famous picture, “The Man with the Hoe,” was saved with other paintings and tapestries in the collection of William H. Crocker.

Mr. Crocker, who was in New York, said about the rescue of the paintings (Head is Mr. Crocker’s butler):

“I am much gratified at the devotion Head displayed in saving my pictures and tapestries at such a time. Besides the ‘Man with the Hoe,’ I have pictures by Tenniel, Troyon, Paul Potter, Corot, Monet, Renoir, Puvis de Chavannes, Pissaro, and Constable. The tapestries consisted of six Flemish pieces dating from the sixteenth century, of which the finest is a ‘Resurrection.’ [Pg 218]It is a splendid example of tissue d’or work, and was once the property of the duc d’Albe.”

On April 20 Bishop Coadjutor Greer of the Protestant Episcopal church of New York announced that this prayer had been authorized to be used in the churches of that diocese for victims of the earthquake:

“O Father of Mercy and God of all comfort, our only help in time of need, look down from heaven, we humbly beseech thee, behold, visit and relieve thy servants to whom such great and grievous loss and suffering have come through the earthquake and the fire.

“In thy wisdom thou hast seen fit to visit them with trouble and to bring distress upon them. Remember, O Lord, in mercy and imbue their souls with patience under this affliction.

“Though they be perplexed and troubled on every side, save them from despair and suffer not their faith and trust in thee to fail.

“In this our hour of darkness, when thou hast made the earth to tremble and the mountains thereof to shake, be thou, O God, their refuge and their strength and their present help in trouble.

“And for as much as thou alone canst bring light out of darkness and good out of evil, let the light of thy loving countenance shine upon them through the cloud; let the angel of thy presence be with them in their sorrow, to comfort and support them, giving strength to the weak, courage to the faint and consolation to the dying.

“We ask it in the name of him who in all our afflictions is afflicted with us, thy son, our Saviour, Jesus Christ. Amen!”

Mrs. A. G. Pritchard, wife of a San Francisco manufacturer, who, with her husband, was on her way home from Europe to San Francisco, became suddenly insane at the Union Station in Pittsburgh Pa., when she alighted to get some fresh air.

The Pritchards were hurrying to San Francisco with the [Pg 219]expectation of finding their three children dead in the ruins of their home.

Landing in New York April 24, the Pritchards learned that their home had been destroyed before any of the occupants had had an opportunity to get out.

Mr. Pritchard said that his information was that the governess was dying in a hospital, and from what he has heard, he had no hope of seeing his children alive.

At Philadelphia a physician told Mr. Pritchard that his wife was bordering on insanity. At the station Mrs. Pritchard shrieked and moaned until she was put into the car, where a physician passenger volunteered to care for the case.

On the afternoon of the fire the police broke open every saloon and corner grocery in the saved district and poured all malt and spirituous liquors into the gutters.

San Francisco was famous for the excellence of its restaurants. Many of these were known wherever the traveler discussed good living. Among them were the “Pup” and Marschand’s in Stockton street; the “Poodle Dog,” one of the most ornate distinctive restaurant buildings in the United States; Zinkand’s and the Fiesta, in Market street; the famous Palace grill in the Palace hotel; and scores of bohemian resorts in the old part of San Francisco. They are no more.

Down near the railroad tracks at what used to be Townsend street, food was mined from the ruins as a result of a fortuitous discovery made by Ben Campbell, a negro. While in search of possible treasure he located the ruins of a grocery warehouse, which turned out to be a veritable oven of plenty. People gathered to this place and picked up oysters, canned asparagus, beans, and fruit all done to a turn and ready for serving.

For a time there was marked indignation in San Francisco caused by the report that the San Franciscans, in their deep-grounded prejudice, had discriminated against the Chinamen in the relief work. This report was groundless. The six Chinese [Pg 220]companies, or Tongs, representing enormous wealth, had done such good work that but little had been necessary from the general relief committee, and, besides, the Chinese needed less. No Chinaman was treated as other than a citizen entitled to all rights, which cannot be said under normal conditions on the Pacific coast. Gee Sing, a Chinese member of the Salvation Army, had been particularly efficient in caring for his countrymen.

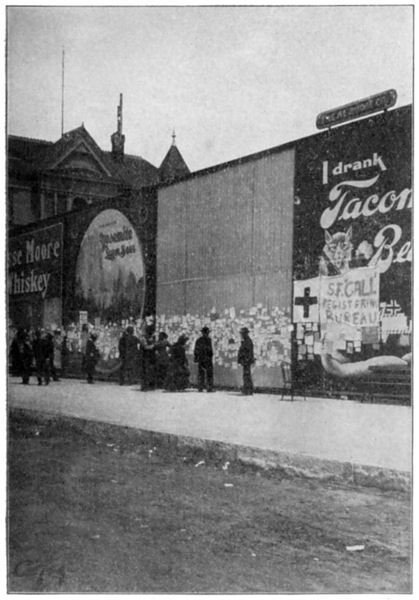

The San Francisco daily newspapers, all of which were burned out, were prompt in getting in shape to serve their subscribers. On Thursday morning, the day after the fire, the best showing the morning journals could make was a small combination sheet bearing the unique heading, “Call-Chronicle-Examiner.” It was set up and printed in the office of the Oakland Tribune, gave a brief account of the great disaster, and took an optimistic view of the future of the stricken city. The day after the papers, though still printed in Oakland, appeared under their own headings and with a few illustrations, showing scenes in the streets of San Francisco.

S. M. Pencovic, a San Francisco druggist, on arriving in Chicago from Paris, said he had a premonition of disaster, which impelled him to hasten home, several days before the earthquake. He left for San Francisco to search for his father and mother, who are among the missing.

“For several days I felt as if something awful was about to happen,” said he. “So completely did the feeling take possession of me that I could not sleep at night. At last I could stand it no longer, and I left Paris April 14, four days before the upheaval.

“I embarked on La Savoie at Havre. I tried to send a wireless message, but could receive no answer.

“The day after the catastrophe the captain of the ship called me to his cabin and told me he had just received a wireless message that San Francisco had been destroyed by an earthquake. I was not surprised.”

[Pg 221]At the Presidio, where probably 50,000 people were camped, affairs were conducted with military precision. Here those who are fortunate enough to be numbered among the campers were able now and then to obtain a little water with which to moisten their parched lips, while rations, owing to the limited supply, were being dealt out in the smallest quantities that all may share a bit. The refugees stood patiently in line and the marvelous thing about it all was that not a murmur was heard. This characteristic is observable all over the city. The people were brave and patient and the wonderful order preserved by them had been of great assistance. Though homeless and starving they were facing the awful calamity with resigned fortitude.

In Oakland the day after the quake messages were stacked yards high in all the telegraph offices waiting to be sent throughout the world. Conditions warranted utter despair and panic, but through it all the people were trying to be brave and falter not.

Oakland temporarily took the place of San Francisco as the metropolis of the Pacific coast, and there the finance kings, the bankers and merchants of the San Francisco of yesterday were gathering and conferring and getting into shape the first plans for the rebuilding of the burned city and preventing a widespread financial panic that in the first part of the awful catastrophe seemed certain.

Resting on a brick pile in Howard street was a young Swedish woman, whose entire family had perished and who had succeeded in saving from the ruins of her home only the picture of her mother. This she clutched tightly as she struggled on to the ferry landing—the gateway to new hope for the refugees. A little farther along sat a man with his wife and child. He had had a good home and business. Wrapped in a newspaper he held six hand-painted dinner plates. They were all he could dig out of the debris of his home, and by accident they had escaped breakage.

[Pg 222]“This is what I start life over again with,” he said, and his wife tried to smile as she took her child’s hand to continue the journey. Thousands of these instances are to be found.

Owing to the energetic efforts of General Funston and the officials of the Spring Valley Water Company the sufferers in all parts of the city were spared at least the horrors of a water famine. As soon as it was learned that some few mercenaries who were fortunate enough to have fresh water stored in tanks in manufacturing districts were selling it at 50 cents per glass, the authorities took prompt action and hastened their efforts to repair the mains that had been damaged by the earthquake shocks.

John Singleton, a Los Angeles millionaire, his wife and her sister, were staying at the Palace Hotel when the earthquake shock occurred.

Mr. Singleton gave the following account of his experience: “The shock wrecked the rooms in which we were sleeping. We managed to get our clothes on and get out immediately. We had been at the hotel only two days and left probably $3,000 worth of personal effects in the room.

“After leaving the Palace we secured an express wagon for $25 to take us to the Casino near Golden Gate Park, where we stayed Wednesday night. On Thursday morning we managed to get a conveyance at enormous cost and spent the entire day in getting to the Palace. We paid $1 apiece for eggs and $2 for a loaf of bread. On these and a little ham we had to be satisfied.”

Copyright 1906 by Tom M. Phillips.

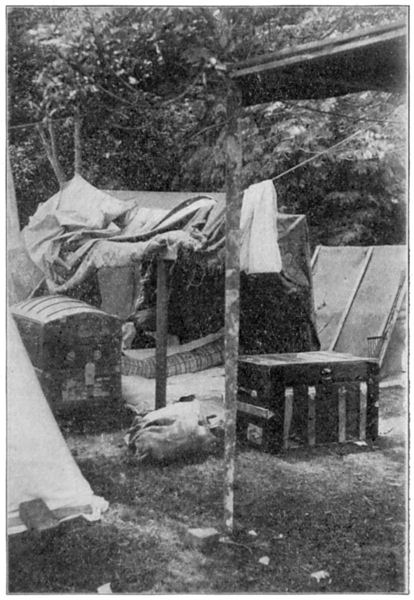

RANDOLPH STORAGE.

Walls shaken down by the earthquake.

Copyright 1906 by Tom M. Phillips.

DESTROYED SWITCHBOARD.

The electric lighting company.

Copyright 1906 by Tom M. Phillips.

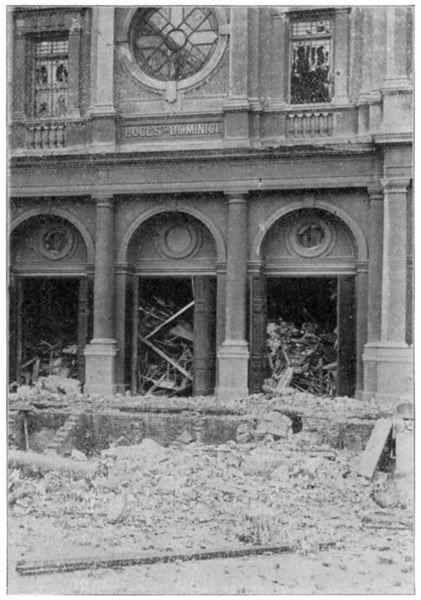

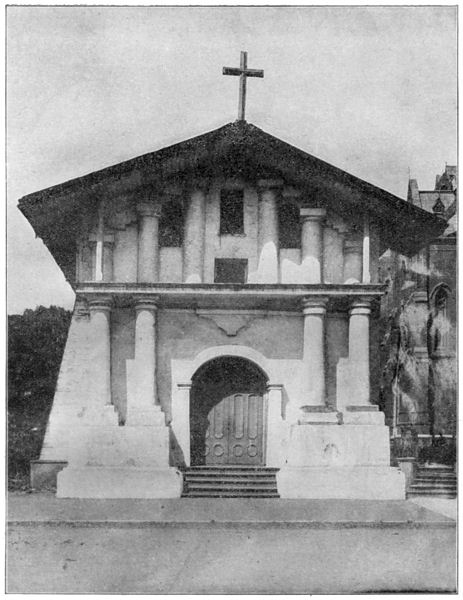

ST. DOMINICI CHURCH.

A part of the steeple shaken out by the earthquake.

Copyright 1906 by Tom M. Phillips.

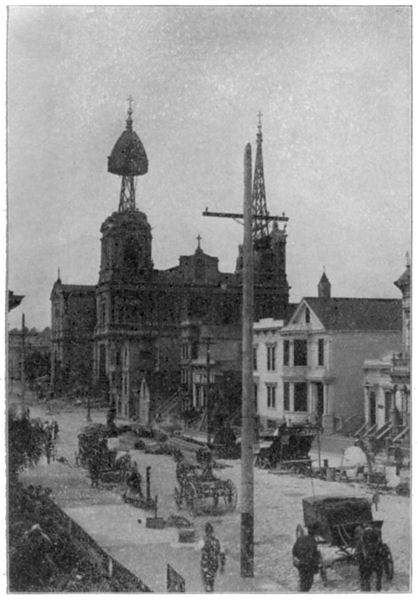

ST. DOMINICI CHURCH.

A view of the wreck which tells its own story.

John A. Floyd, a Pullman conductor on the Northwestern railroad, living in Chicago, gave a lengthy and vivid description of the quake and its effects.

“If I live a thousand lifetimes I will never forget that night,” he said. “Words are too feeble, entirely too inadequate, to portray the fear that clutched the human breast. The most graphic pen could not faithfully portray the sickening horror of that night.

“Plaster falling from the walls in my room in the fourth floor [Pg 225]of the Terminal Hotel in Market street aroused me from a sound sleep about 5 o’clock in the morning. I sat up in bed, and got out onto the floor. The building was shaking like a reed in a storm, literally rocking like a hammock. It was impossible for me to stand. Another shock threw me heavily to the floor. I remained there for what seemed hours to me. Then I crawled on hands and knees to the door, and succeeded in unlocking it with much difficulty. I was in my night clothes, and without waiting to even pull on a pair of shoes I made my way down those swaying stairs as rapidly as I could.

“When I reached the street it was filled with half mad unclothed men, women, and children, running this way and that, hugging and fighting each other in their frenzy.

“The loud detonations under the earth enhanced the horror. The ground kept swaying from side to side, then roaring like the waves of the ocean, then jolting in every conceivable direction.

“Buildings were parting on all sides like egg shells, the stone and brick and iron raining down on the undressed hundreds in the streets, killing many of them outright and pinning others down to die slowly of torture or be roasted alive by the flames that sprang up everywhere around us.

“When things had quieted somewhat, I went back to the hotel to dress, and discovered that the entire wall of my room had fallen out.

“I succeeded in finding most of my clothes, and after donning them hastily went back to the work of rescue. When I got back to the street from the hotel the entire district seemed to be in flames. Fire seemed to break out of the very earth on all sides of Market street, eating up buildings as if they were so many buildings of paper. A big wholesale drug house on Seventh street exploded, throwing sparking and burning embers high into the air. These fiery pieces descended on the half-clad people in the streets, causing them to run madly for places of safety, almost crazy with the pain.

[Pg 226]“Soon the improvised hearses began to arrive. Out of every building bodies were taken like carcasses out of a slaughter pen. Automobiles, carriages, express wagons, private equipages, and vehicles of all kinds were pressed into service and piled high with the bodies. Everywhere these wagon loads of dead bodies were being dragged through the streets, offering a spectacle to turn the most stout-hearted sick.

“With three or four sailors I went up to Seventh street to assist a number of men, women and children who had become entombed under the debris of a flat building.

“They were so tightly wedged in that we were unable to offer them any help and had to stand by and hear their cries as they were slowly roasted to death by the ever increasing flames. I can hear the cries of one of those women ringing in my ears yet—I guess I always will.

“I guess pretty nearly every bone in her body was broken. As we stood by helplessly she cried over and over again:

“‘Don’t let me die like this. Don’t let me roast. I’m cooking, cooking alive. Kill me! Shoot me—anything! For God’s sake have mercy!’

“Others joined her in the cry and begged piteously to be quickly killed before the flames reached them.

“By this time the street level had become so irregular that it was almost impossible to drag the dead wagons over them.

“Dynamite was then brought into use and the buildings were blown up like firecrackers. Flying debris was everywhere in the air, and another mad rush for safety was made, the almost naked people falling over each other in their frantic efforts to get out of the danger.

“While this excitement was at its height a man dressed only in his underclothing made his appearance among the people in a light gasoline runabout. At top speed he ran into a crowd of women, knocking them down and injuring at least a dozen. [Pg 227]Then he turned back and charged them again. He had gone mad as a result of the scenes of death and destruction.

“Some one called for a gun, hoping that they might stop the fellow by shooting him. None was to be had, and after a desperate fight with sailors who succeeded in getting into the machine he was overpowered and turned loose.

“Everybody in the crowd, I believe, was temporarily crazy. Men and women ran helter-skelter in nothing but their night gowns, and many of them did not have on that much.”

Mrs. J. B. Conaty, of Los Angeles, was in Oakland at the time of the shock and felt the vibrations. “The suddenness with which it came upon the people,” she said, “was the most appalling thing. When I looked across the bay at ’Frisco from the Oakland shore the city seemed peacefully at sleep, like a tired baby beside its mother. With my next glance at the city I was turned almost sick.

“The ground was shaking beneath me and I thought that the end of the world was at hand. Buildings were falling to the right and left. The earth was groaning and rocking, and flames were shooting high into the sky. Soon the sound of the dynamiting reached us and buildings began to fly in the air like fireworks.

“The sea lashed itself into a fury and beat upon the shores as if it too sought to escape nature’s wrath. Over across the bay all was disorder. In the glare of the blood red flames reflected against sky and sea, white robed, half naked men and women could be seen wildly running about.

“Some of them ran to the water’s edge and threw themselves in and others less frantic had to battle with them to haul them out.

“It seemed as if every man, woman and child in ’Frisco was running toward the ferry docks. When the boat arrived on our side of the shore it was packed with men and women, none of whom seemed to be in their right senses. Many of them jumped from the boat as soon as it was made fast and ran at top speed [Pg 228]through the streets of Oakland until forced to fall through sheer exhaustion.

“One woman in the crowd had nothing on but a night gown. In her arms she carried a 3-year-old girl who was hanging tightly to a rag doll and seemed to be the only one in the vast crowd that was unafraid. Where all these people went to I have no idea.

“I stood on the Oakland side watching ’Frisco devoured. In a space of time so short that it all seems to me like a dream now the whole city, slumbering peacefully but a moment before, presented a perdition beside which Dante’s inferno seems to pale into insignificance.”

The looters early began operations in the stricken city. The vandal thinking that law and order had gone in the general crash filled his pockets as he fled.

It was the relic hunter who opened the door to the looter. The spirit which sends the tourist tapping about the ruins of the Parthenon, awoke in San Francisco. Idle and curious men swarmed into the city, poking about in the ruins in the hope of finding something worth carrying away as a souvenir of the greatest calamity of modern times.

Scores of men and women were seen digging in the ruins of one store. They were disinterring bits of crockery, china and glassware. Strangely enough, a great deal of this sort of ware had been protected by a wall which stood through quake and fire. One woman came toiling out over a pile of brick, covered with ashes and dust, her hair dishevelled and hands grimy, but she was perfectly happy.

“See,” said she, “I found half a dozen cups and saucers as good as new. They are fine china and they will be worth more than ever now.”

I asked her if she needed them.

“Oh, dear no!” said she, laughing. “I live over in Oakland. I just wanted them to keep as souvenirs!”

Some hard-hearted jokers were abroad also. Humor dies [Pg 229]hard, and perhaps it is just as well that it does, for the six men who started the bogus bread lines would have needed much of it if the soldiers had caught them.

The people of San Francisco had become accustomed to eating out of the hand. They put in long hours every day standing in line waiting for something to be given out. Many of them did not know what was being distributed, but they knew it would be good, so they fell into line and waited.

There were thousands of people in San Francisco who fell into a line every time they saw one. They had the bread line habit.

This impressed itself on these six men, for they went about the town and every time they found a promising spot they lined up and looked expectant. Men came and fell in behind. Women with baskets joined the brigade and in ten minutes these sidewalk comedians had a string a block long behind them and more coming every minute. Then the six jokers slipped away and left the confiding ones to wait. It was a mean trick.

The stranger and the wayfarer was made to feel at home anywhere in Oakland and the luxury of sleeping within four walls was not denied to any one. Only a few hardy men who were willing to sacrifice themselves for the good of the weaklings went without covering. The people stripped the portieres and hangings from their walls, tore up their carpets and brought in every spare piece of cloth which would do for a night’s covering. The women and children who preferred to stay indoors and on hard floors were taken care of in the public halls, the school buildings, and the basements of the churches. Beds were improvised of sheets and hay and the weaker refugees, who were beginning to go down under the strain, slept comfortably. Oakland did nobly. People shared their beds with absolute strangers, and while the newcomers in the park camps were dead to the world, those who came the day before cheered up considerably. One camp of young men got out a banjo and sang for the entertainment of the crowd.

CHAPTER XVIII.

DISASTER AS VIEWED BY SCIENTISTS.

Scientists are Divided Upon the Theories Concerning the Shock That Wrought Havoc in the Golden Gate City—May Have Originated Miles Under the Ocean—Growth of the Sierra Madre Mountains May Have Been the Cause.

THE subterranean movement that caused the earthquake at San Francisco was felt in greater or less degree at many distant places on the earth’s surface. The scientists in the government bureaus at Washington believe that the subterranean land slide may have taken place in the earthquake belt in the South American region or under the bed of the Pacific Ocean. San Francisco got the result of the wave as it struck the continent, and almost simultaneously the instruments in Washington reported a decided tremor of the earth, and the oscillations of the needle continued until about noon.

At the weather bureau the needle was taken from the pivot and had to be replaced before the record could be continued. Other government stations throughout the country also noted the earthquake shock, and they agree in a general way that the disturbance began according to the record of the seismograph at nineteen minutes and twenty seconds after 8 o’clock. This would be the same number of minutes and seconds after 5 o’clock at San Francisco, which accords entirely with the time of the disaster on the Pacific Coast.

There seems to be no reason to believe the earthquake shock in San Francisco had any direct connection with the eruption of Vesuvius. That eruption had been recorded from day to day [Pg 231]on the delicate instruments established by the weather bureau at the lofty station on Mount Weather, high up in the Virginia hills. This eruption of Vesuvius did not disturb the seismograph even at the period of great activity, but apparently Vesuvius and Mount Weather were like the lofty poles of two wireless telegraph stations, and between them there passed electrical magnetic waves encircling the earth. The records made at Mount Weather were of the most distinct character, but they showed disturbances in the air of a magnetic type and did not indicate any earthquake.

In explaining the San Francisco trembling, C. W. Hays, the director of geology in the geological survey, explained that earthquakes are, according to modern scientific theory, caused by subterranean land slides, the result of a readjustment as between the solid and the molten parts of the earth’s interior.

“The earth,” he said, “is in a condition of unstable equilibrium so far as its insides are concerned. The outer crust is solid, but after you get down sixty or seventy miles the rocks are nearly in a fluid condition owing to great pressure upon them. They flow to adjust themselves to changed conditions, but as the crust cools it condenses, hardens, and cracks, and occasionally the tremendous energy inside is manifested on the surface.

“When the semi-fluid rocks in the interior change their position there is a readjustment of the surface like the breaking up of ice in a river, and the grinding causes the earthquake shocks which are familiar in various parts of the world. The earthquake at San Francisco was probably local, although the center of the disturbance may have been thousands of miles away from that city.”

Prof. Willis L. Moore, the chief of the weather bureau, in talking of the records of the earthquake in his department, said:

“We have a perfect record of this earthquake, although we are thousands of miles away from the actual tremor itself. There were premonitory tremblings, which began at 8:19 and continued [Pg 232]until 8:23 or thereabout. Then there was severe shock which threw the pen off the cylinder.

“According to our observations here there was a to and fro motion of the earth in the vicinity of Washington amounting to about four-tenths of an inch at the time of its greatest oscillation. These movements kept up in a constantly decreasing ratio until nearly half an hour after noon.

“San Francisco may have been a long way away from the real earthquake and merely have been within the radius of severe action so as to produce disastrous results. It is quite likely, in fact, that the greatest disturbance may have taken place beneath the bed of the Pacific Ocean.

“If it resulted in an oscillation of the earth of only a few inches there would be no likelihood of a great tidal wave. If, however, there was produced a radical depression in the bed of the ocean, the sinking of an island, or some other extraordinary disturbance, a tidal wave along the Pacific Coast would almost certainly be one of the events of this great disaster.

“There are apparently three distinct weak spots in the United States, which are peculiarly subject to earthquake shocks, and we are likely sooner or later to hear from all of them in connection with the shock at San Francisco. There is one weak area along the southern Atlantic coast in the vicinity of Charleston, another is in Missouri, and the third includes the Pacific Coast from a point north of San Francisco down to and beyond San Diego.”

In describing the instruments at the weather bureau which make the record of earthquakes, even when the movement is so small that the ordinary person does not recognize it, Prof. Moore said:

“The apparatus we have is a pen drawing a continuous line on a cylinder which revolves once every hour and is worked continuously by clockwork in an exact record of time. It moves in a straight line when there is no disturbance, and it jumps from right to left and back again when there are serious oscillations [Pg 233]of the earth. The extent of these movements of the pen measures the grade of the oscillation. You may think it is a fantastic statement, but this seismographic pen is adjusted so delicately that it will register your step in its vicinity.

“The instrument is mounted on a solid stone foundation and what it registers is the effect of your weight pressing upon the earth. It is easy to see, therefore, that the record we have obtained of this earthquake shows a few preliminary tremblings, which seem to be premonitions, for about four minutes, then a great crash which threw the pen off the cylinder and finally a period of nearly four hours, during which there were slight tremblings of the earth, this latter period marking the readjustment after the actual shock.”

Most of the scientists were inclined to believe that the boiling process in the interior of the earth, although it goes on continuously, is subject to periods of greater or less activity. This activity may be, however, purely local, according to the scientific theory, for otherwise there would be eruptions in all the active volcanoes of the earth at the same time, and there would be earthquakes in every one of the areas where there is liability to seismic disturbances.

One government scientist in discussing the San Francisco earthquake said: “If we could have been right here in the vicinity of Washington a few hundreds of thousands of millions of years ago, we should have seen earthquakes that were earthquakes. The Alleghanies were broken up by great convulsions of the earth, and it is probable that this North American continent of ours was rocked a foot or two at a time, causing a tremendous crash of matter and the reorganization of the world itself.

“The crust, while not necessarily thinner, is not so solid. In cooling it has cracked and left fissures or caverns or jumbled strata of softer material between harder rocks, so that it is peculiarly subject to earthquakes.”

Maj. Clarence E. Dutton, U. S. A., retired, the most famous [Pg 234]American expert on seismic disturbances, said it was probably the greatest earthquake that has occurred in this country since 1868. He declared that it undoubtedly would be followed by disturbances of less intensity in the same quarter. He stated most emphatically that the eruption of Vesuvius had no bearing whatsoever on the disturbance on the Pacific Coast.

J. Paul Goode, a professor in geology in the University of Chicago, attributes the cause of the Frisco earthquake to the Sierra Madre mountains, but not in a volcanic way, for he also claims that lava had nothing to do with the California shock. The shocks, he showed, can be attributed to mountains without volcanoes in their midst. The Sierra Madres are growing, he said, and for this reason they have shaken the city of San Francisco. He says that the gradual growing of mountains causes the underlying blocks of the earth’s crust to slip up and down and shape the top of the earth in their vicinity when they fall any great distance.

His ideas upon the subject are: “I figure that the earthquake which caused so much damage in San Francisco came from what we call the focus of disturbance. This focus at San Francisco is seven miles below the surface of the earth. As the Sierra Madre mountains grow, a phenomenon which is constantly going on, the blocks of earth below change positions; as a large block falls a series of shocks travels, up and down much the same way as the rings in the water travel out from the point at which a pebble strikes. When the vibration reaches the surface crust a severe shaking of the country adjacent is the result.

“From the actions of the earth in April of 1892, when such a severe shock was felt in San Francisco, I have no doubt but that a second earthquake will follow closely upon the one of yesterday, as the second followed the first in 1892. In that year the first came upon the 19th of April and the second upon the 21st.”

Of 948 earthquake shocks that have been recorded in California previous to 1887, 417 were most active in San Francisco. [Pg 235]The seismographs which record the merest tremors and determine the place of the shock show that 344 have occurred since 1888. Half of the sum total have occurred in the vicinity of the gate city and for this reason it is believed that the severe shock of April 18 was the final fall of a crust of the earth which has been gradually slipping for centuries, causing from time to time the slight shocks.

The seismic physics of San Francisco and its immediate neighborhood have engaged the careful study of physical geographers. The commonly accepted opinion is one which was formulated by Prof. John Le Conte, professor of geology in the University of California, and one of the world’s geological authorities. His explanation is based upon the mountain contours of the coast of California from the Santa Barbara channel northward to the Golden Gate. In this region are represented two peninsulas, one visible, the other to be discovered through examination of the altitudes upon the map corresponding to existing geological features. This second and greater peninsula comprises the Monte Diablo and Coast ranges, separated from the Sierra elevation by the alluvial soil of the low-lying valley of the San Joaquin. This valley is contoured by the level of 100 feet and lower for a considerable portion of its length, and practically all of it lies below the level of 500 feet. The partition thereby accomplished between the Sierra mountain mass and the coastal mountains is sufficiently pronounced to indicate what was at no remote period an extensive peninsula.

This valley of the San Joaquin lies above the line of a geological fault, at a depth which can only be estimated as somewhere about a mile. The artesian well borings which have been abundantly prosecuted in the counties of Merced, Fresno, Kings and Kern afford evidence looking toward such a determination of bedrock depth. On the ocean side the continental shelf is extremely narrow. The great peninsula presents a most precipitous [Pg 236]aspect toward the ocean basin. It is interrupted at intervals by deep submarine gorges extending close to the shore.

The oceanic basin of the Pacific is throughout a region of volcanic upheaval and seismic disturbance.

Conditioned on the one side by the known fault of the San Joaquin Valley and on the other by the volcanic activity of the Pacific basin, the greater peninsula of San Francisco in particular has always been subject, so far as the memory of white settlers can go, to frequent shocks of earthquake. In the last score or more of years seismographic observatories have been maintained at several points about San Francisco bay, and the records have been sufficiently studied to afford data for comprehension of the varied earth waves which have made themselves felt either to the perception of the citizens of the Golden Gate or to the sensitive instruments. Such observations have been conducted by Prof. George Davidson, for many years in charge of the Coast and Geodetic Survey upon the Pacific Coast; by Prof. Charles Burckhalter, of the Chabot Observatory, in Oakland, and by the staff of the Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton.

Careful inspection of these records shows that two systems of earthquake disturbances act upon San Francisco. Those of the lighter series show a wave movement beginning in one of the easterly quadrants and more commonly in the southeastern. This series of light shocks is attributed to the slip along the line of the San Joaquin fault. While they may occur at any season of the year, they are more frequently observed when the San Joaquin river is running bank high under the influence of the melting snows in the foothills of the Sierra. That such a condition has recently existed is made clear by the report within less than a month of floods in the interior valleys of the State. Assuming, as the geologists do, that the fault in the valley lies near the roots of the Monte Diablo range, on the western edge of the alluvial plain, it will be seen that the physical factors involving the slip are very simple. There is a wide, flat plain bounded on the [Pg 237]west by a line of weakness in the rock supports. When this plain is carrying an abnormal weight of water the tendency is to break downward at the line of the fault. This tendency will produce a jar in the mountain mass which will be rapidly communicated to its farthest extremity.

The earthquakes which have their origin in the disturbances to which the oceanic basin is subject always approach San Francisco from the direction of the southwest quadrant. These have been uniformly more violent than those whose origin is attributed to the San Joaquin fault. While the records of San Francisco earthquakes up to the present have exhibited a mild type, the damage to property having hitherto been slight, it would appear from the extent and violence of the present temblor that both causes had for once united.

The possibility of such simultaneous action of the two known seismic factors of the greater peninsula had been foreseen by Prof. Le Conte. He stated that if at any time an earthquake wave of only moderate violence should come in from the oceanic basin in sufficient strength to jar the coastal mountain masses at a period when the San Joaquin Valley was bearing its maximum weight of water the conditions would be ripe for simultaneous shocks from the southwest and from the southeast. In such a condition, while neither of the shocks by itself would be capable of doing any great amount of damage to buildings in San Francisco, the combination of two distinct sets of waves might prove too much for any work of man to withstand.

In spite of the declarations of some scientists that there can be no possible connection between the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the earthquake of San Francisco, others are inclined to view certain facts in regard to recent seismic and volcanic activity as, to say the least, suggestive.

There is one very remarkable circumstance in regard to all this activity. All the places mentioned—Formosa, Southern Italy, Caucasia and the Canary Islands—lie within a belt bounded by [Pg 238]lines a little north of the fortieth parallel and a little south of the thirtieth parallel. San Francisco is just south of the fortieth parallel, while Naples is just north of it. The latitude of Calabria, where the terrible earthquakes occurred last year, is the same as that of the territory affected by yesterday’s earthquake in the United States.

There is another coincidence, which may be only a coincidence, but which is also suggestive. The last previous great eruption of Vesuvius was in 1872, and the same year saw the last previous earthquake in California which caused loss of life.

Camille Flammarion expressed the opinion that the earthquake at San Francisco and the eruption at Vesuvius are directly connected. He also sees a connection between the renewed activity of Popocatepetl, Mexico’s well-known volcano, and the disturbance on the Western coast. He says that, though the surface of the earth is apparently calm, “there is no real equilibrium in the strata of the earth,” and that the extreme lateral pressure which is still forming mountains and volcanoes along the Western coast brought about an explosion of gases and the movement of superheated steam several miles below San Francisco, resulting in an earthquake.

Another theory is that the earth in revolving is flattening at the poles and swelling at the equator, and the strata beneath the surface are shifting and sliding in an effort to accommodate themselves to the new position. Other scientists scout this idea, saying that earthquakes are not caused by the adjustment of the surface of the earth, but by jar and strain as the earth makes an effort to regain its true axis.

As regards the possible connection between volcanoes and earthquakes, it is known that a violent earthquake, whose shocks lasted several days, accompanied the eruption of Vesuvius in the year 79, when Pompeii and Herculaneum were destroyed. In 1755 thousands upon thousands of people lost their lives in the memorable earthquake at Lisbon, in Portugal. At the same time [Pg 239]the warm springs of Teplitz, Bohemia, disappeared, later spouting forth again. In the same year an Iceland volcano broke forth, followed by an uprising and subsidence of the water of Loch Lomond in Scotland. The eruption of Vesuvius in 1872 was followed soon after by a serious earthquake in California.

Coming to the present year, it is noticed that the earthquake in the island of Formosa, in which 1,000 people lost their lives, was followed by the eruption of Vesuvius on April 8. Soon after came the second great shock in Formosa, in which there was an even greater loss of life.

Later there were two earthquake shocks in Caucasia. At the same time the news of this appeared there was a report of renewed activity on the part of a volcano in the Canary Isles, which had long been dormant. In the United States two volcanoes which have been regarded as extinct for more than a century—Mount Tacoma and Mount Rainier—began to emit smoke. In regard to Tacoma, Dr. W. J. Holland, head of the Carnegie Institute at Pittsburg, says: “There is no doubt that there has been a breakdown and shifting of strata, perhaps at a very great depth, in the region of San Francisco. There certainly is great connection between this earthquake and recent private reports which have come to me of intense volcanic activity on the part of Mount Tacoma.”

On the other hand, leading scientists contend that these instances are mere coincidences. “If there is any connection between Vesuvius and the Caucasus and Canary Isles earthquakes other places would have suffered too; New York, for instance, is on the same parallel,” says Prof. J. F. Kemp, of Columbia University.

Although each of these scientists has the most absolute faith in his theory, he really knows no more about the facts than any boy on the street. No one has ever descended into the interior of the earth and investigated the heart of a volcano but Jules Verne, and he only in his mind. What is needed now is exact [Pg 240]information. The San Francisco catastrophe will teach many lessons, and among them the necessity for the close study of both volcanoes and earthquakes. There is no reason why earthquakes and other internal disturbances cannot be observed just as closely as the weather. In fact, it is entirely probable that the time will come when a seismological bureau will exist for the study of earthquakes, just as there is a Weather Bureau for observation of the weather, and it will be the business of its officials to prophesy and warn of approaching internal disturbances of the earth, just as the weather men announce the approach of bad weather. Government observation stations will be established, exact records will be kept, and in the course of time we shall learn exactly what earthquakes are and what are their causes.

Among other lessons that the disaster has taught is that the much-maligned skyscraper is about the safest building there is. Its steel-cage structure, with steel rods binding the stone to its wall, has stood the test and has not been found wanting. Of all the mighty buildings in San Francisco those of the most modern structure alone survived. Their safety in the midst of collapsing buildings of mortar and brick argues well for like structures in other cities.

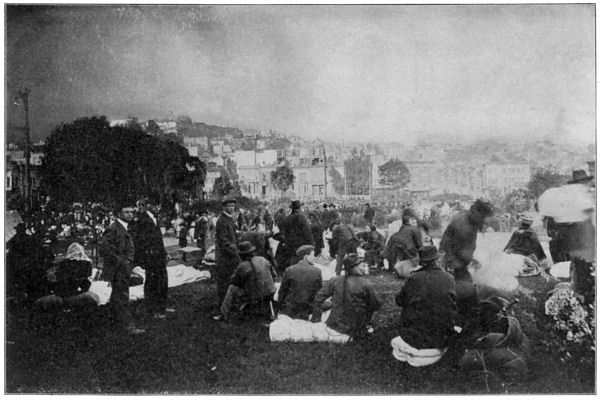

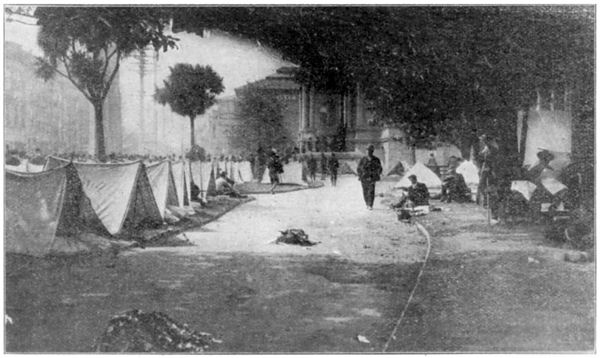

Copyright by R. L. Forrest 1906.

CHINESE REFUGEES IN WASHINGTON SQUARE PARK.

It was estimated that as many as 10,000 Chinese were in this park at the time this photograph was taken.

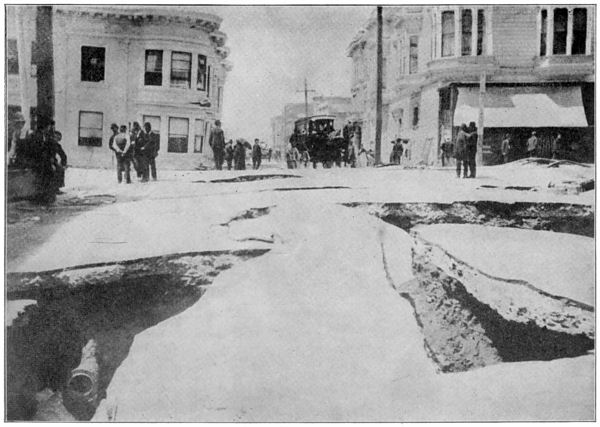

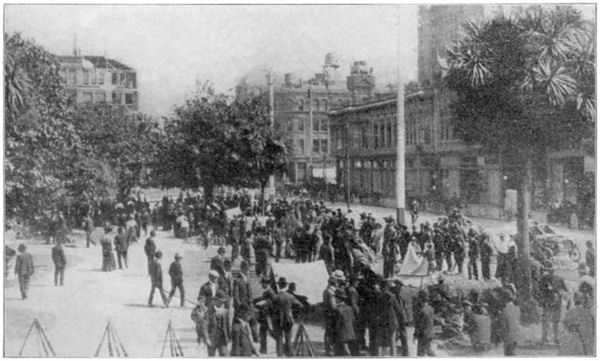

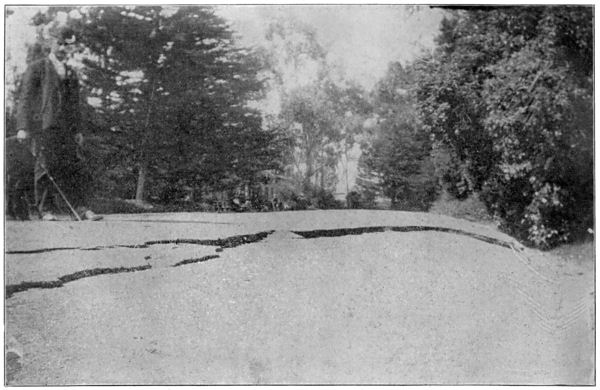

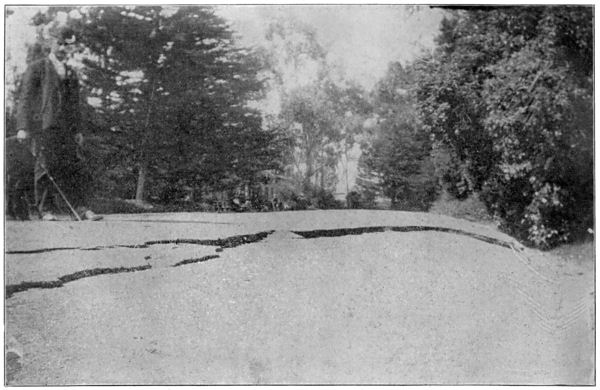

FLAT BUILDING SUNK INTO EARTH.

A view of the great fissures in earth caused by earthquake. One story of the flat building on corner sunk into the ground. The water main was broken, which cut off the water supply. No water to fight the fire or quench the thirst.

Mr. Otis Ashmore declared that the regions lying along the Pacific coast contain several of the moving strata which cause earthquakes. He said:

“While much concerning the origin of earthquakes is still a matter of doubt in the minds of scientific men, it is now generally conceded that the real cause is the sudden slipping and readjustment of the strata of rocks with the crest of the earth. As the earth is slowly cooling a very slow contraction of the earth’s crust is constantly going on, and as this crust consists very largely of stratified layers of rock, the enormous forces arising from this contraction are resisted by the solid rock.

“Notwithstanding the apparent irresistible nature of these layers of rock, they slowly yield to the enormous lateral pressure [Pg 243]of contraction and gradually huge folds are pushed up in long mountain ranges. Usually this process goes on so slowly and gradually that the yielding of the rock masses takes place without noticeable jar, but occasionally a sudden slip occurs under the gigantic forces, and an earthquake is the result. This slip is usually only a few inches, but when two continents fall together for only a few inches enormous energy is developed.

“Such slips usually occur along the line of an old fissure previously formed, and the depth below the surface of the earth varies from one to twelve miles. Thus places situated near these old internal fissures are more likely to experience earthquakes than those farther away. It is a well known geological fact that the Pacific coast in California contains several of these fissures and earthquakes are more common there. The entire western part of the United States has been slowly rising for many centuries, and the shifting of soil due to erosion and transportation doubtless contributes to produce these seismic disturbances.

“Earthquakes are more common than most persons think. Modern instruments for detecting slight tremors within the earth’s crust show that there is scarcely an hour in the day free from these shocks. In mountain regions, and especially in the highest and youngest mountains, erosion is most rapid, and on the sea bottom, along the margin of the continents sedimentation is greatest. In these regions, therefore subterranean temperature and pressure changes are most rapid and earthquakes most frequent.

“A study of earthquakes develop these general facts. The origin is seldom more than twelve miles below the surface; the size of the shaken region bears a certain relation to the depth of the origin or focus, the smaller shaken region indicating a relatively shallow origin; the energy of the shock is approximately indicated by the area of the shaken region; the origin is seldom a point, but generally a line many miles in length; the subterranean stress is not relieved by a single movement, but rather by a quick succession of movements causing a series of jars.

[Pg 244]“The transmission of an earthquake shock through the earth takes place with wonderful rapidity. The elastic wave varies in velocity from 800 to 1,000 feet per second in sand or clay to three miles per second in solid granite.

“Sometimes these vibrations are of such a character as to be imparted to the air, and their transmission through the air outstrips the transmission through the earth and the ear detects the low rumbling sounds before the shock is felt.

“If the origin of the shock is under the sea near the coast any upheaval of the bottom of the ocean that frequently accompanies an earthquake, gives rise to a great tidal wave that frequently inundates the neighboring coast with much damage.

“While the phenomena of earthquakes and volcanoes are usually associated in the same region, one cannot fairly be said to be the cause of the other. Both are rather effects of a common cause, or rather of common causes, the chief of which is the shrinking and readjustment of the rocky strata within the earth. The suggestion that there is some physical connection between the recent eruptions of Vesuvius and the earthquake at San Francisco does not accord with the generally accepted views of geologists concerning these phenomena.

“It is probably true that a critical condition of stress between two gigantic and contending forces may be touched off, as it were, by any feeble force originating at a distance. Thus a distant volcanic eruption or earthquake shock may determine the climax of stress in a given portion of the earth, which will produce an earthquake. Observations show that more earthquakes occur near the full and the new moon than at other times. This is probably due to the fact that at these times the gravitation of the sun and moon are combined, and their effect upon the earth is greater. We can see this effect in the higher tides at new and full moon. But these forces, it will be seen, are the occasions, and not the causes of earthquakes.

“The probable recurrence of the San Francisco earthquake is [Pg 245]a matter of great uncertainty. In general, whenever the internal stress of the forces that give rise to earthquakes is relieved there is usually a long period of quiescence in the strata of the earth, but in the course of time, especially in regions of recent and rapid geological changes, such as is the case on the Pacific coast, there is almost certain to be recurrences of earthquake shocks from time to time.

“The geological forces may, however, gradually adjust themselves, and it may be many centuries before such a dynamic crisis will arise as that which has just convulsed a continent.”

California has had a number of great earthquakes. The records go back to the earthquake at Santa Ana in 1769. Not very much is known of this earthquake, though a church was built there and dedicated as Jesus de los Temblores.

Another one occurred at Santa Barbara in 1806, and still another in 1812. The Old Mission, about the only building there at that time, on both occasions practically had to be rebuilt.

Hittell’s History of California says that “slight shocks of earthquakes are not infrequent, but none of really violent or dangerous character has been known to occur. An old or badly constructed building has occasionally been thrown down, and a few people have been killed by falling roofs or walls. But there has been nothing in the experience of the oldest inhabitants to occasion or justify fear or dread. The first one of which there is any full record occurred on October 11, 1800, and consisted of six consecutive shocks, and it tumbled down the habitations of San Juan Bautista.

“The most disastrous shock occurred in December, 1812, when the church of San Juan Capistrano was thrown down and forty Indians killed by its fall. The same shock extended northwestward and damaged the churches of San Gabriel, San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Inez and Purisima. In 1818 the church of Santa Clara was damaged, and in 1830 the church of San Luis Obispo.”

CHAPTER XIX.

CHINATOWN, A PLAGUE SPOT BLOTTED OUT.

An Oriental Hell within an American City—Foreign in its Stores, Gambling Dens and Inhabitants—The Mecca of all San Francisco Sight Seers—Secret Passages, Opium Joints and Slave Trade its Chief Features.

TO a visitor unacquainted with oriental customs and manners the most picturesque and mysterious spot in the region of the Golden Gate was Chinatown, now blotted out, which laid in the heart of San Francisco, halfway up the hillside from the bay and was two blocks wide by two blocks long. In this circumscribed area an Oriental city within an American city, more than 24,000 Chinese lived, one-half of whom ate and slept below the level of the streets. The buildings they occupied were among the finest that were built in the early days of the gold fever. What was at one time the leading hotel of the city was as full of Chinese as a hive is full of bees, for they crowd in together in much the same way. As the gold fever attracted the Chinese to the Pacific coast, San Francisco was made a headquarters and the Orientals soon established themselves in a building on the side hill. As they continued to swarm over, gradually the American tenants were crowded out until a certain section was set apart for the Chinese residents and Chinatown became as distinct a section of the city as the Bowery in New York used to be, “where they do such things and say such things.” The time to see Chinatown was after dark, from ten at night to four in the morning, and a day and a night spent in the district would give you a very fair idea of Chinatown as it was.

[Pg 247]The streets were narrow and steep, paved with rough cobblestone. The fronts of the buildings had been changed to conform with the Chinese idea of architecture. Wide balconies and gratings and fretwork of iron painted in gaudy colors gave an Oriental touch. The fronts were a riot of color. The fronts of the joss houses and the restaurants were brightened with many colored lanterns, quaint carved gilded woodwork, potted plants and dwarf trees. Up and down these narrow streets every hour in the twenty-four you could hear the gentle tattoo, for he seemed never to sleep, never to be in a hurry and always moving. Stop on any corner five minutes and the sight was like a moving picture show. It was hard to make yourself believe that you were not in China, for as near as is possible Chinatown had been converted into a typical Chinese community. You heard no other language spoken on the streets or in the stores except by tourists, “seeing the sights.” Chinese characters adorned the windows and store fronts, the merchants in the stores were reading Chinese newspapers, the children playing on the streets jabbered in an unknown tongue, and every man you met had a pigtail hanging down his back. The streets were full of people, but there were no crowds and neither in the day nor night could you see a drunken Chinaman.

The first floor of nearly every building in Chinatown was occupied by a store or market. Most of the goods sold were imported from China. In every store there was but one clerk who could talk fair English but the bookkeeping was done in Chinese and money was counted in Chinese fashion. In the botanic stores dried snakes and toads were sold for use in compounding potions to drive away evil spirits and baskets of ginseng roots were displayed in the windows. The clothing stores handled Chinese goods exclusively and in the shoe stores beautifully embroidered sandals with felt soles an inch thick were sold for a dollar a pair. Occasionally in one of the jewelry stores a workman welded a solid gold bracelet to the arm of a Chinaman, [Pg 248]who, afraid of being robbed of his gold, had it made into a bracelet and welded to his wrist. In the markets you found an endless display of fish, poultry and vegetables. The chickens were sold alive. The dried fish came from China. All the vegetables sold in Chinatown were raised in gardens on the outskirts of the city from seed sent over from China and some of the specimens were odd looking enough. The Chinese vegetables thrive better in the soil of California than in China and Chinese vegetables raised in the San Francisco district were sent to all the mining camps in the Rockies and as far away as Denver. Some of the Chinese squashes are four feet long. Everything that can be imported from China at a profit was shipped over and the rule among the Chinese was to trade as little as possible with foreigners.

The Chinaman is thrifty and if it were not for gambling and one or two other vices they would all be rich, for they are industrious.

The Chinaman does not go much on strong drink and in many ways is a good citizen, but he does love to smoke opium and to gamble. It was easy to gain access to an opium den if you had a guide with you. The guides, many of whom are Chinese, speak English, and the English guides speak Chinese. The guides got a dollar apiece from the party of visitors they piloted about and a percentage from all moneys spent by the party in the stores, saloons, restaurants, theaters and the dives. In return they paid for the opium that was smoked in the dens for the edification of the visitors and dropped a tip here and there as they went from place to place. Most of the opium dens were underground.

The majority of the people of Chinatown lived in what were little better than rat holes, dark, poorly ventilated little cells on the side of narrow passages in basements. The rich merchants and importers lived well, but the middle and poorer classes lived in the basements where rent was cheap. Of the 24,000 Chinese population only about 900 were women so Chinatown was a bachelor’s town by a large majority, though some of the residents had [Pg 249]wives in China to whom they expected to return some day. The rule in the basements was for ten men to sleep in a room six by ten feet and do their cooking over a little charcoal fire in one corner of the room. The beds they slept in were simply bunks. The population of Chinatown had somewhat decreased since the Exclusion act was passed. Few Chinamen came over and many, having saved up a little fortune, had gone back to China to stay. Of the entire population of Chinatown there were about 1,000 who voted; they constituted the native born element. The men and women dress much alike.

One of the sights which the inquisitive traveller to the Pacific coast rarely missed was the Chinese theater. Entrance was gained through the rear from an alley by the payment of 50 cents for a ticket. After walking down a narrow passageway, climbing up two flights of stairs and down three ladders one reached the green room in the rear of the stage where one saw the actors in all the glory of Oriental costume. No foreigners, as Americans were regarded, were allowed in any part of the theater except on the stage where half a dozen chairs were reserved on one side for visitors who came in the back way. There was no drop curtain in front of the stage and the orchestra was located in the rear of the stage. The orchestra would attract attention anywhere. The music was a cross between the noise made by a boiler shop during working hours and a horse fiddle at a country serenade.

As one walked along the streets of Chinatown he noticed on many doorways a sign which read something like this: “Merchants’ Social Club. None But Members Admitted.” There would be a little iron wicket on one side of the door through which the password goes and some Chinese characters on the walls. There were dozens of these clubs in Chinatown, all incorporated and protected by law. But they were simply gambling joints into which men of other nationalities were not admitted, and where members could gamble without fear of [Pg 250]interruption by the police. Chinamen are born gamblers and will wager their last dollar on the turn of a card. Perhaps if 25,000 Americans or Englishmen or Russians were located in the heart of a Chinese city without any of the restraining influences of home life, they would seek to while away their idle hours at draw poker or as many other forms of gambling as John Chinaman indulges in. The Chinamen have little faith in one another so far as honesty goes. In many of the clubs the funds of the club are kept in a big safe which in addition to having a time lock, has four padlocks, one for each of the principal officers, and the safe can only be opened when all four are present. Often when the police raided a den that was not incorporated they found that the chips and cards had disappeared as if by magic and the players were sitting about as unconcerned as though a poker game had never been thought of. An advance tip had been sent in by a confederate on the private Chinese grapevine telegraph.

The troubles that arise between members of a Chinese secret society are settled within the society, but when trouble arises between the members of rival secret societies then it means death to somebody. For instance, a Chinaman caught cheating at cards is killed. The society to which the dead man belongs makes a demand on the society to which the man who killed him belongs for a heavy indemnity in cash. If it is not paid on a certain date, a certain number of members of the society, usually the Highbinder or hoodlum element, is detailed to kill a member of the other society. A price is fixed for the killing and is paid as soon as the job is done. The favorite weapon of the Highbinder is a long knife made of a file, with a brass knob and heavy handle. The other weapon in common use is a 45-calibre Colt’s revolver. The first one of the detail that meets the victim selected slips up behind him and shoots or stabs him in the back. It may be in a dark alley at midnight, in an opium den, at the entrance to a theater, or in the victim’s bed. If the assassin is arrested the society furnishes witness to prove an alibi and money [Pg 251]to retain a lawyer. Another favorite pastime of the Highbinder who is usually a loafer, is to levy blackmail on a wealthy Chinaman. If the sum demanded is not paid the victim’s life is not worth 30 cents. One of the famous victims of the Highbinders in recent years in San Francisco was “Little Pete,” a Chinaman who was worth $150,000 and owned a gambling palace. He refused to be held by blackmailers and lost his life in consequence.

The police of San Francisco took no stock in a Chinaman’s oath as administered in American courts. A Chinaman don’t believe in the Bible and therefore does not regard an oath as binding. In one instance it is asserted the chief had been approached by a member of one of the strongest secret societies and asked what attorney was to prosecute a certain Highbinder under arrest. Asked why he wished to know, he stated frankly that another man was about to be assassinated and he desired to retain a certain lawyer in advance to defend him if he was not already employed by the commonwealth. It is no easy matter for the police to secure the conviction of a Chinaman charged with any crime, let alone that of murder. There is only one place where a policeman will believe a Chinaman. That is in a cemetery, while a chicken’s head is being cut off. If asked any questions at that time, after certain Chinese words have been repeated, a Chinaman will tell the truth, so the police believe. Although all Chinaman are smooth faced and have their heads shaved they do not “look alike” to the policemen, who have no trouble in telling them apart. This, of course, applied only to the policemen detailed to look after Chinatown. If it were not that the Chinamen kill only men of their own race and let alone all other men, the citizens of San Francisco would have sacked and burned Chinatown. Once the Highbinders were rooted out of the city, and before the catastrophe they were going to do so again.

Some time ago a Chinese shrimp fisherman incurred the displeasure of the members of another society and he was kidnapped in the night and taken to a lonely, uninhabited island some miles [Pg 252]from San Francisco, tied hand and foot and fastened tight to stakes driven in the ground and left to die. Two days later he was found by friends, purely by accident and released, famished and worn out, but he refused to tell who his captors were, and again become a victim of the terrible Highbinders, the curse of the Pacific coast.

Incidents of the above characters nearly always ending in murder, were so common that the wealthy and powerful Chinese Six Companies, the big merchants of the race, held years ago meetings with the purpose of bringing the societies to peace and while they often succeeded the truce between them was only temporary.

Of all the dark, secretive and lawless Chinese villages that dot the wayward Pacific slope, the one that looks down on the arm of San Francisco Bay, just this side of San Pedro Point, is the most mysterious and lawless. The village hasn’t even a name to identify it, but “No Sabe” would be the most characteristic title for the settlement, because that is the only expression chance visitors and the officers of the law can get out of its sullen, stubborn, suspicious inhabitants.

They don’t deride the laws of this land. They simply ignore them.

They are a law unto themselves, have their own tribunals, officers, fines and punishments and woe betide the member who doesn’t submit. He might cry out for the white man’s law to protect him, but long before his cry could reach the white man’s ear it would be lost in that lonely, secretive village and the first officer that reached the place would be greeted by the usual stoical, “No sabe.”

Police and other investigations showed that for years past the slavery of girls and women in Chinatown was at all times deplorable and something horrible. At an investigation, a few years ago, instituted at the instance of the Methodist Mission, [Pg 253]some terrible facts were elicited, the following indicating the nature of nearly all:

The first girl examined testified that her parents sold her into slavery while she was only fifteen years of age. The price paid was $1,980, of which she personally saw $300 paid down as a deposit. Before the final payment was made she escaped to the mission.

The second, an older girl, lived in a house of ill fame for several years before she made her escape. She testified that she was sold for $2,200 by her stepmother. The transaction occurred in this city. She talked at length of the conditions surrounding the girls, including the infamous rule that they must earn a certain sum each day, and the punishments that follow failure. This girl said she knew from other girls of her acquaintance that many white men were in the habit of visiting the Chinese houses.

The third girl who testified said she was sold at a time when slaves were scarcer and higher in price than they are now, and brought $2,800 at the age of fifteen. She, too, was positive that white men visited the Chinese houses of ill fame.

One of the women of the mission showed the committee three little girls, mere babies, who had been rescued by the mission. Two of them were sold by their parents while they were still in arms. The first brought $105 when three months old and another was sold at about the same age for $150. All three were taken from the keepers of houses of ill fame and were living regularly in the houses when rescued.

But there was also a better side to Chinatown. The joss house was an interesting place. It was but a large room without seats. A profusion of very costly grill work and lanterns adorned the ceilings and walls; instruments of war were distributed around the room, and many fierce looking josses peered out from under silken canopies on the shrines. In one corner was a miniature wooden warrior, frantically riding a fiery steed toward a joss who stood in his doorway awaiting the rider’s coming. A teapot of [Pg 254]unique design, filled with fresh tea every day, and a very small cup and saucer were always ready for the warrior. This represented a man killed in battle, whose noble steed, missing his master, refused to eat and so pined away and died. A welcome was assured to them in the better land if the work of man can accomplish it. The horse and rider were to them (the Chinese) what the images of saints are to Christians. In another corner was a tiny bowl of water; the gods occasionally come down and wash. At certain times of the year, direct questions were written on slips of paper and put into the hands of one of the greatest josses. These disappear and then the joss either nodded or shook his head in answer. On the altar, or altars, were several brass and copper vessels in which the worshiper left a sandalwood punk burning in such a position that the ashes would fall on the fine sand in the vessel. When one of these became full it was emptied into an immense bronze vase on the balcony, and this, in turn, was emptied into the ocean. The Chinese take good care of their living and never forget their dead. Once a year, the fourteenth day of the seventh month, they have a solemn ceremony by which they send gold and silver and cloth to the great army of the departed.

A furnace is a necessity in a joss house. It is lighted on ceremonial days and paper representing cloth, gold and silver is burned, the ashes of the materials being, in their minds, useful in spirit land. Private families send to their relatives and friends whatever they want by throwing the gold, the silver and the cloth paper, also fruits, into a fire built in the street in front of their houses. The days of worship come on the first and fifteenth of each month.

Of the deaths in Chinatown by the earthquake and fire no reliable list has been possible but in estimating the victims the construction of the district should be regarded as an inconsiderable factor.

CHAPTER XX.

THE NEW SAN FRANCISCO.

A Modern City of Steel on the Ruins of the City that Was—A Beautiful Vista of Boulevards, Parks and Open Spaces Flanked by the Massive Structures of Commerce and the Palaces of Wealth and Fashion.

WITH superb courage and optimism that characterize the American people, San Francisco lifted her head from the ashes, and, as Kipling says, “turned her face home to the instant need of things.”

Scorched and warped by days and nights of fire, the indomitable spirit of the Golden Gate metropolis rose on pinions of hope, unsubdued and unafraid.

Old San Francisco was an ash heap. From out the wreck and ruin there should arise a new San Francisco that would at once be the pride of the Pacific coast and the American nation and a proud monument to the city that was.

Temporarily the commerce of the city was transferred to Oakland, with its magnificent harbor across the bay, and at once a spirit of friendly rivalry sprung up in the latter city. Oakland had been the first haven of refuge for the fleeing thousands, but in the face of the overwhelming disaster the sister city saw a grand opportunity to enhance its own commercial importance.

But the spirit of San Francisco would brook no successful rivalry and its leading men were united in a determination to rebuild a city beautiful on the ashen site and to regain and re-establish its commercial supremacy on the Pacific coast.

With the fire quenched, the hungry fed, some sort of shelter provided, the next step was to prepare for the resumption of business and the reconstruction of the city. Within ten days [Pg 256]from the first outbreak of flames the soldiers had begun to impress the passer-by into the service of throwing bricks and other debris out of the street in order to remove the stuff from the path of travel.

Some important personages were unceremoniously put to work by the unbiased guards, among them being Secretary of State Charles Curry of Sacramento.

The people of San Francisco turned their eyes to a new and greater city. Visitors were overwhelmed with terror of the shaking of the earth, they quailed at the thought of the fire. But the men who crossed the arid plains, who went thirsty and hungry and braved the Indian and faced hardships unflinchingly in their quest for gold over two-thirds of a century ago had left behind them descendants who were not cowards. Smoke was still rising from the debris of one building while the owner was planning the erection of another and still better one.

The disaster had made common cause, and the laboring man who before was seeking to gouge from his employer and the employer who was scheming to turn the tables on his employes felt the need of co-operation and cast aside their differences, and worked for the common cause, a new and a greater San Francisco.

Fire could not stop them, nor the earthquake daunt. They talked of beautiful boulevards, of lofty and solid steel and concrete buildings and of the sweeping away of the slums. They talked of many things and they were enthusiastic. They said that the old Chinatown would be driven away to Hunter’s Point in the southeastern portion of the city near the slaughter-houses. They said the business district should be given a chance to go over there where it belonged, by right of commanding and convenient position. They talked of magnificent palaces to take the place of those that had fallen before the earthquake, fire and dynamite. Courage conquers. We are proud of the American spirit which arises above all difficulties.

[Pg 257]But there are some things which could not be replaced. There could not be another Chinatown like the old one, with all its quaint nooks and alleys. All this was gone and a new Chinatown must seem like a sham. There were no more quaint buildings in the Latin quarter, with their old world atmosphere.