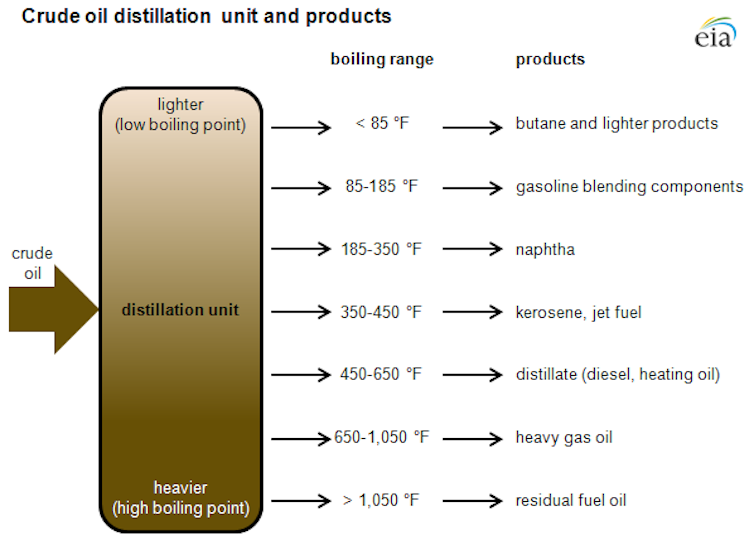

- Although Americans will soon be getting more stolen gasoline, it costs a lot more at the pump than the legal stuff. Venezuelan crude is heavy and sour, meaning it is extremely dense and contains a high percentage of sulfur.

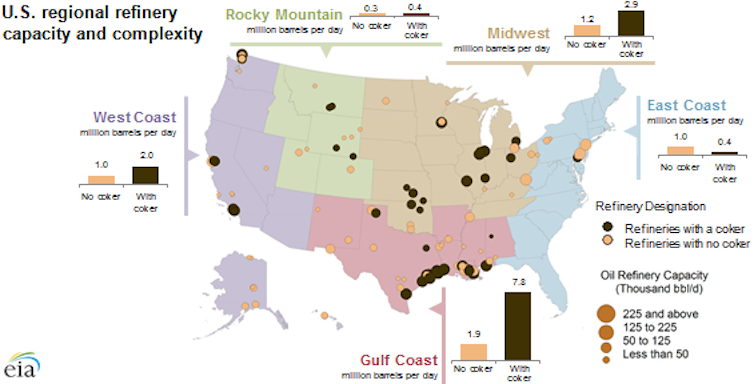

- Only specialized “complex” refineries can handle the dense petroleum produced in Venezuela and remove its unwanted sulfur.

- More than half of U.S. refinery capacity is ‘complex,’ meaning it requires at least some heavy crude oil to operate properly.

- The U.S. refineries that can do this are mainly located along the Gulf Coast, in the Midwest and in California.

T=1765759119 / Human Date and time (GMT): Mon, 15th Dec. 2025, 00.38.

____

Pirates wearing FBI badges boarded a tanker off Venezuela - VIDEOS

- What an utter shame - the Americans have been stealing oil from Iraq for years, as well as about 80% of Syria's oil production.

- Now the morale of the greedy thieves has completely collapsed.

- They are stealing oil from the poor people of the communist country at gunpoint.

- The Venezuelan 'Merey crude' tanker, 'Skipper', is being taken to Texas and the oil is being re-labeled 'West Texas Intermediate crude'.

- Total 1.1. million barrels 'for free'.

- Profit before refining into gasoline, (WTI crude): $58.04/bbl x 1.1 million bbl = $63,844,000.

- Trump SACKS US Admiral Before US-Venezuela War? BIG BLOW As US BOMBS Drug Boats, Kills Civilians.

https://graviolateam.blogspot.com/2025/12/pirates-wearing-fbi-badges-boarded.html

___

The tanker seized by the Americans near Venezuela had a crew of Russians on board.

Russian blogger, analyst, television commentator, and activist Oleg Tsarev drew attention to the lawless incident on his blog on December 14, citing the details he had learned. Citing a subscriber's information, he reported that the information about the Russian crew of the hijacked tanker had been confirmed

According to his data, the tanker is managed by Aquamarine Ship Management. Some of the crew, including the captain, mechanics, and several motor mechanics, arrived in Venezuela from Moscow via Istanbul on October 30, 2025. The crew consists of Russians, Ukrainians, and other Slavs. They swear at each other. political Topics are strictly prohibited. The video shows footage of a new crew arriving on the tanker on November 1, 2025.

- wrote the Tsarev.

– summed up Tsarev.

SOURCE

https://en.topcor.ru/66920-na-zahvachennom-amerikancami-tankere-vozle-venesujely-okazalsja-jekipazh-s-rossijanami.html

___

Maritime News

High-risk rated VLCC Skipper seized by US following pattern of AIS spoofing, dark STS and false reflagging

Last updated on 12 Dec, 06:50

Published 11 Dec, 14:28

Last updated on 12 Dec, 06:50

Published 11 Dec, 14:28

Senior Risk & Compliance Analyst

Contributing authors: Ana Subasic, Trade Risk Analyst at Kpler (asubasic@kpler.com) and Yuan Li, Junior Risk & Compliance Analyst at Kpler (yli@kpler.com)

Market & trading calls:

- Increased near-term flows disruption risk: Venezuelan STS operations now carry materially higher exposure.

- Direct enforcement risk: associated high-risk vessels increasingly face targeted intervention.

- Trade-route monitoring: tracking pressure will intensify in relevant regions including off coast Malaysia for China-bound crude volumes.

US forces seized the OFAC sanctioned oil tanker VLCC Skipper on 10 December after satellite imagery confirmed undisclosed loading of Merey crude at Venezuela’s José terminal in mid-November. This development reflects escalating geopolitical risk in the region and renewed scrutiny of maritime activity linked to sanctioned trade flows.

Kpler Risk and Compliance had previously rated Skipper as high risk based on a consistent pattern of deceptive behavior, including false reflagging, AIS spoofing, and a 6 December ship-to-ship transfer with Neptune 6 - one of the highest-risk vessels flagged by Kpler´s predictive scoring method based on repeated patterns of deceptive shipping practices. These indicators collectively signaled elevated enforcement likelihood ahead of the US action.

Use of a false Guyana flag triggered heightened behavioral scrutiny

The issues identified with Skipper’s registry were not administrative mistakes but deliberate steps to create a temporary appearance of legitimacy. In sanctions-evasion patterns, false-flagging is an important functional tactic: it obscures ownership, weakens the reliability of vessel identity data, and introduces uncertainty that can slow enforcement. In practical terms, once a vessel is operating under an unstable or rapidly changing flag, the credibility of all other reported data - including ownership, routing, and commercial purpose -is also scrutinized.

From a risk-methodology standpoint, the vessel showed a clear mismatch between its digital and physical signatures in the weeks before the seizure. Skipper broadcast AIS positions near Guyana’s offshore blocks while satellite imagery placed it at Venezuela’s José Terminal. This indicates deliberate AIS manipulation, not technical error. Digital–physical divergence is a high-confidence indicator because it removes the ambiguity of AIS-only analysis and demonstrates that concealment is an active operational choice.

The vessel’s history reinforces this assessment. Skipper previously recorded an 83-day AIS gap on an Iran-linked voyage and engaged in multiple spoofing events designed to mimic normal commercial traffic. These are not isolated incidents but a consistent behavioral pattern. That pattern is a key predictor of enforcement risk, signaling that the vessel is operating as part of an illicit logistics network rather than acting opportunistically.

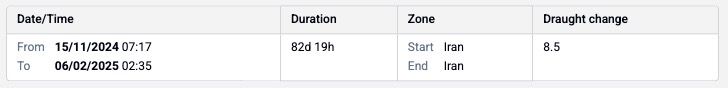

83-day AIS gap during a previous Iran-linked voyage with a change of draught during that period of time - Kpler.

83-day AIS gap during a previous Iran-linked voyage with a change of draught during that period of time - Kpler.

Furthermore, Skipper displayed a clear convergence of high-risk indicators: prolonged dark periods, sanctioned crude loadings, ship-to-ship transfers involving restricted cargo, and repeated calls at high-risk port facilities including Venezuela’s José Terminal, Iran’s Kharg Island, and Syria’s Banias Port.

Voyages that Skipper declared through her AIS data since 1st of June 2025 - Kpler.

Voyages that Skipper declared through her AIS data since 1st of June 2025 - Kpler.

The final trigger occurred days before US interception, when Skipper completed a Merey crude loading and initiated another STS operation, indicating imminent onward movement of illicit cargo.

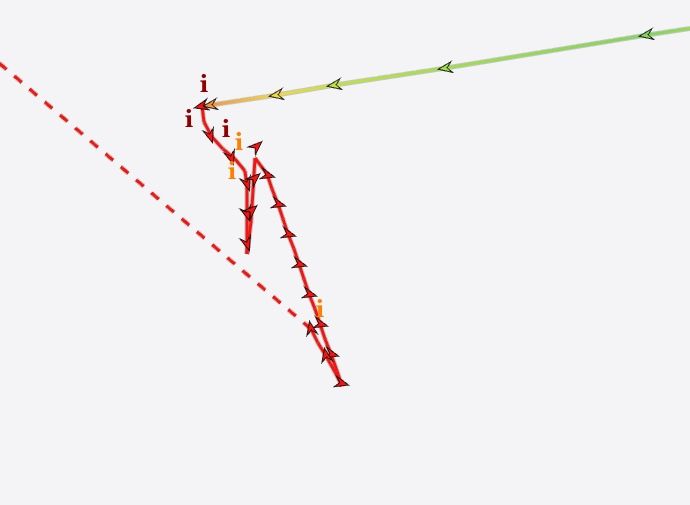

Skipper showed a zig-zag movement pattern - typical for spoofing - between 28 October and 7 November, right before the AIS signal disappeared - Kpler AIS.

Skipper showed a zig-zag movement pattern - typical for spoofing - between 28 October and 7 November, right before the AIS signal disappeared - Kpler AIS.

Imagery confirming Skipper’s STS transfer with Neptune 6 in the Caribbean on 7 December - conducted during an AIS gap and involving Venezuelan crude- further reinforced this pattern. At that point, the vessel’s concealment framework had fully unraveled: the false flag lacked credibility, its AIS narrative had been discredited, and the historical evidence signaled a high-certainty compliance breach.

STS transfer of SKIPPER with NEPTUNE 6 at Caribbean Sea with Venezuelan crude oil on between 6-7 December 2025 during an AIS gap - European Union Copernicus Sentinel and Kpler.

For real-time insights on vessel activity and sanctions compliance risk, access Kpler’s proprietary dark activity tracker and flagged vessel alerts.

Keep Reading in Risk and Compliance

U.S. sanctions against Venezuela’s state-owned oil and gas company, along with some government officials and executives, are intended to put pressure on the government headed by Nicolás Maduro.

As the interim director of the Tulane Energy Institute, which tracks energy markets and provides forecasts, and someone with 35 years of oil industry experience, I’m certain that they will also reverberate in this country too – especially in Louisiana, where the oil and gas industry is among the state’s biggest employers.

Economic dysfunction

Despite having the world’s biggest petroleum reserves, Venezuela is now functionally bankrupt and wracked by hyperinflation. Even before the sanctions against Petróleos de Venezuela, the state-owned company known as PDVSA, its crude production was rapidly declining.

Since the late president Hugo Chávez’s election in 1998, followed by Maduro’s rise to power in 2013, the Venezuelan government has effectively destroyed the country’s political institutions, as well as its petroleum-based economy. Oil production has declined by two-thirds, dropping from about 3 million barrels per day in 2000 to around 1.2 million barrels per day in January 2019.

During this long decline, Venezuela collected payments in advance from some of its biggest customers, and therefore cannot collect the revenue now that it would otherwise be obtaining from oil production. Thanks to this practice, it actually doesn’t earn any hard currency from much of the crude that it does export.

Instead, these export earnings actually pay off cash advances from China, Russia and Repsol, the Spanish energy company.

Refineries located along the U.S. Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Texas were just about Venezuela’s last source of hard currency. That came to a halt when the Trump administration slapped sanctions on PDVSA in late January 2019.

Crude quality

You might think that Venezuela could just find new markets for its oil, but that is harder than it may sound.

Venezuelan crude is heavy and sour, meaning it is extremely dense and contains a high percentage of sulfur. Globally, most refineries process light sweet crude into gasoline, jet fuel, diesel and other fuels and products. Only specialized “complex” refineries can handle the dense petroleum produced in Venezuela and remove its unwanted sulfur.

The U.S. refineries that can do this are mainly located along the Gulf Coast, in the Midwest and in California. Most of the rest are located in China and India.

Complex refineries cost about 50 percent more to build. They are also more expensive to operate. They can compete, however, because they use crude from sources like Venezuela that costs less than most crude oil.

Complex refineries

Although U.S. oil production is rising, the domestic industry still needs to import heavy crude to keep the complex refineries operating efficiently. As of early 2019, 90 percent of U.S. imports were heavy crude. Countries that export this heavy petroleum include Mexico, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria and Iran.

Based on their proximity, Canada and Mexico should be good sources for U.S. refiners. However, due to delays in the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline and other pipelines that may eventually run from the northern border to the Gulf Coast, there’s no easy way to replace the blocked shipments from Venezuela.

While Canada is shipping more heavy crude by rail, this approach is much more expensive. It costs about $20 per barrel to ship heavy crude from Canada by rail, versus an estimated $12.50 per barrel via pipelines.

Mexico’s challenge is different. Its heavy crude production has been declining for years. Mexico now imports light crude, as well as gasoline and other refined products from the U.S..

Russia and Saudi Arabia

Another factor is that Saudi Arabia and Russia are cutting their oil production, especially heavy sour crude, as part of an effort to shore up crude prices. Canada is curtailing heavy oil production as well.

It may sound reasonable for the U.S. to simply substitute its own light sweet crude for imported heavy sour crude. But the crude distillation units at complex refineries like those in Louisiana were not designed to use ever higher percentages of light sweet crude.

These refineries require approximately 30 percent heavy crude to operate optimally. At a minimum, the Gulf Coast region needs something like 3.1 million barrels of heavy sour crude per day.

The 563,000 of barrels per day the U.S. was buying from Venezuela in November 2018 only represented 2.8 percent of the roughly 20 million barrels of crude it consumed. But those imports represented a bigger share of the heavy oil the U.S. used: 17 percent, according to my calculations.

Without that supply, Gulf Coast refineries can only reduce throughput and shut down much of their idle sulfur removal capacity.

High stakes for some states

Shutting off heavy crude from Venezuela to Gulf Coast refineries would reduce the production of heavier distillates, such as heating oil, marine fuel oil and diesel.

Jet fuel and gasoline won’t be as affected because these products can be produced from any refinery capable of processing abundant domestic light sweet crude.

I would expect U.S. exports of diesel and heavier distillates to decline as a result, particularly shipments to Latin America and to Europe. After that, domestic supplies to the states supplied by Gulf Coast refineries could be hit as well.

Prices for diesel and fuel oil are likely to rise once supplies are constrained, which could occur quickly because U.S. refineries have little capacity to spare.

Even if U.S. refineries do eventually replace Venezuelan oil, the odds are that crude will come from farther away and cost more. That would, in turn, make diesel cost more, increasing the cost to consumers for everything from food to furniture and flat-screen TVs.

This would happen not just in Louisiana, but in communities far away, as long as the delivery trucks, rail cars and vessels involved have diesel engines. The disruption would illustrate the way that U.S. sanctions intended to apply pressure on other countries can also take a toll on Americans.

- Exports

- Venezuela

- Sanctions

- Mississippi

- Tar sands

- Texas

- Louisiana

- Imports

- heavy oil

- oil refinery

- PDVSA

- Venezuela oil

___

SKIPPER Crude Oil Tanker IMO: 9304667

https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:411444

Latest AIS information

| Navigational status | Underway using Engine |

|---|---|

| Position received | 1 d 4 h 56 mins ago Vessel is Out-of-Range |

| Vessel's local time | 2025-12-13 15:25 (UTC-4) |

| Latitude/Longitude | Upgrade to unlock |

| Speed | 5.6 kn |

| Course | 327 ° |

__

eof

Ei kommentteja:

Lähetä kommentti

You are welcome to show your opinion here!