- The Terrible Tragedy that Befell the People of Our Golden City

- The Metropolis of the Golden Gate, and the Death and Ruin Dealt Many

Adjacent Cities and Surrounding Country.

- Destroying Earthquake Comes Without Warning, in the Early Hours

of the Morning.

- Immense Structures Topple and Crumble.

- Great Leland Stanford University Succumbs.

- Water Mains Demolished and Fire Completes Devastation.

- Fighting Fire With Dynamite.

- Thousands Killed, Maimed, or Unaccounted For.

- Tens of Thousands Without Food or Shelter; Martial Law Declared.

- Property Loss Hundreds of Millions.

- Appalling Stories by Eye Witnesses and Survivors.

- The Disaster as Viewed by Scientists, etc.

Transcriber's Note

Chapters 27 and 33 both end abruptly in the middle of a sentence. There are no omitted page numbers, so it is likely that this was an error made by the publisher when the book was in preparation.

There are some instances where sections of text are repeated, and these are preserved as printed. It may be that this book was published very hurriedly following the earthquake, and that these repetitions were simply missed.

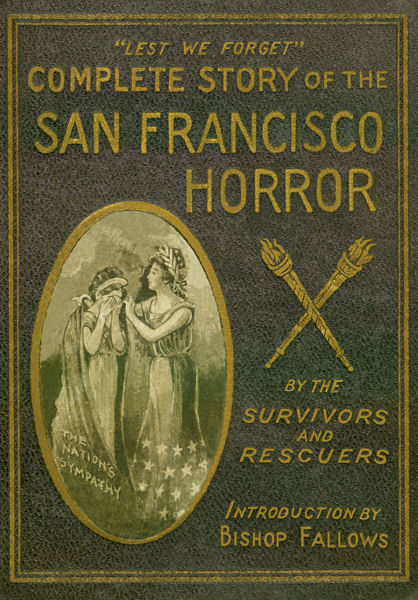

COMPLETE STORY OF THE

|

SCENES OF DEATH AND TERROR

|

Thousands Killed, Maimed, or Unaccounted For; Tens of Thousands Without Food

or Shelter; Martial Law Declared; Millions Donated for Relief; Congress Makes an Appropriation; Sympathetic Citizens Throughout the Land Untie Their Purse-Strings to Aid the Suffering and Destitute; Property Loss Hundreds of Millions; Appalling Stories by Eye Witnesses and Survivors; The Disaster as Viewed by Scientists, etc. |

Comprising Also a Vivid Portrayal of the Recent Death-Dealing

ERUPTION OF MT. VESUVIUS

BY RICHARD LINTHICUM

of the Editorial Staff of the Chicago Chronicle. |

Together with twelve descriptive chapters giving a graphic and detailed account of the most interesting

and historic disasters of the past from ancient times to the present day.

BY TRUMBULL WHITE

Historian, Traveler and Geographer.

Profusely Illustrated with Photographic Scenes of the Great Disasters and Views

of the Devastated Cities and Their People. |

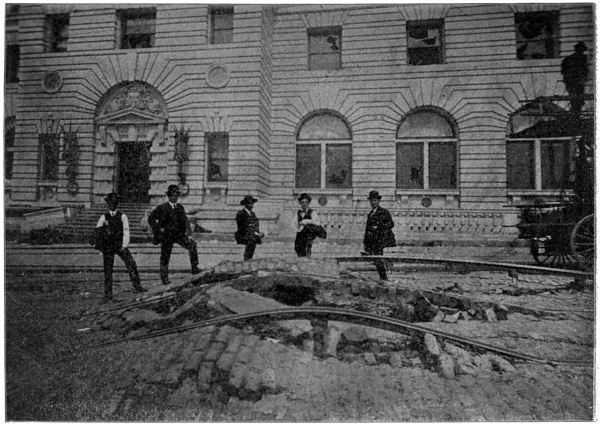

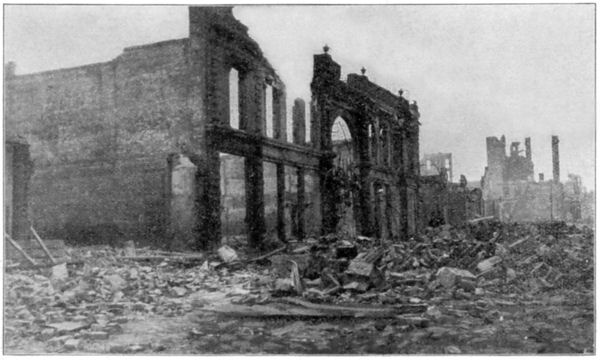

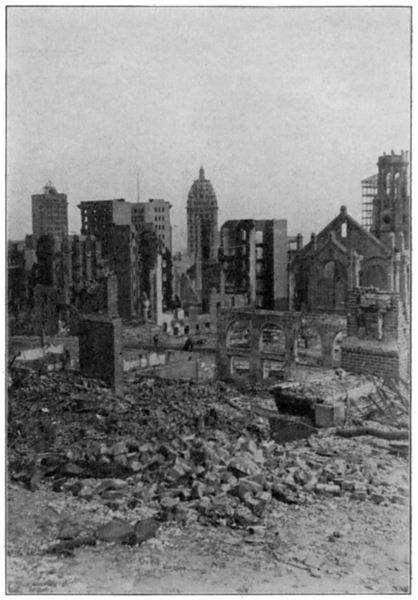

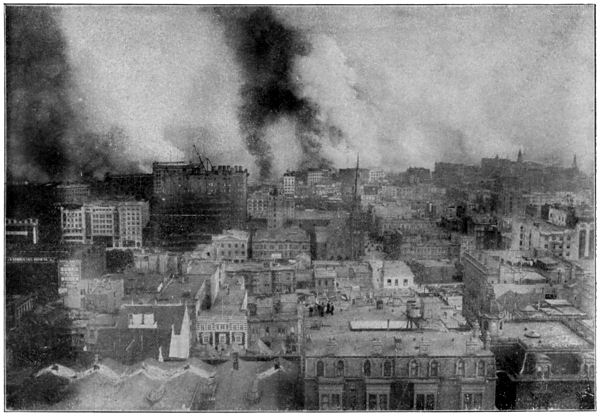

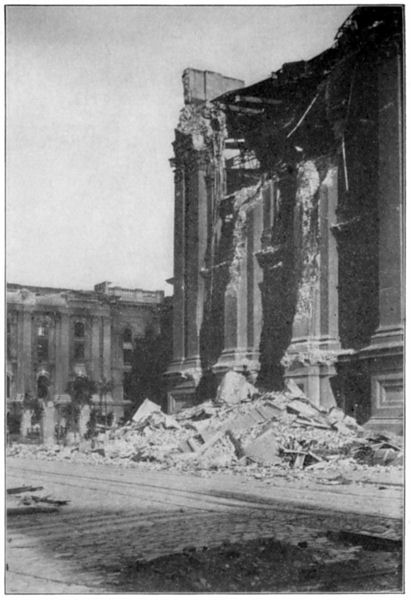

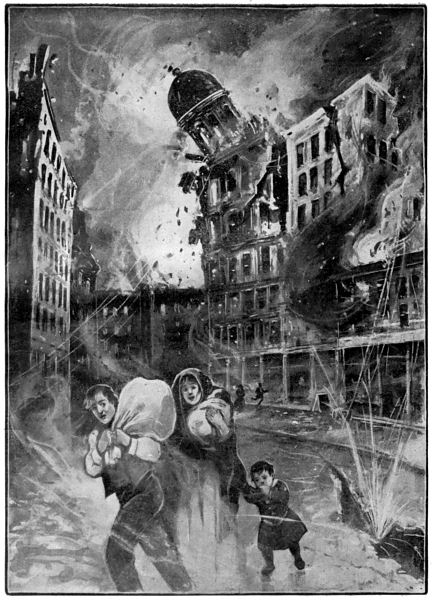

THE AWFUL HORROR OF AN EARTHQUAKE.

Lives, homes and property lost in a few seconds.

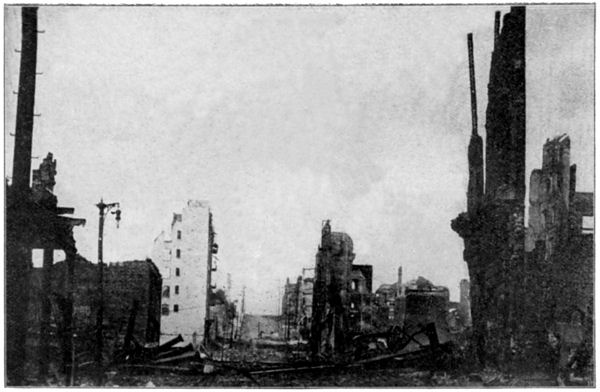

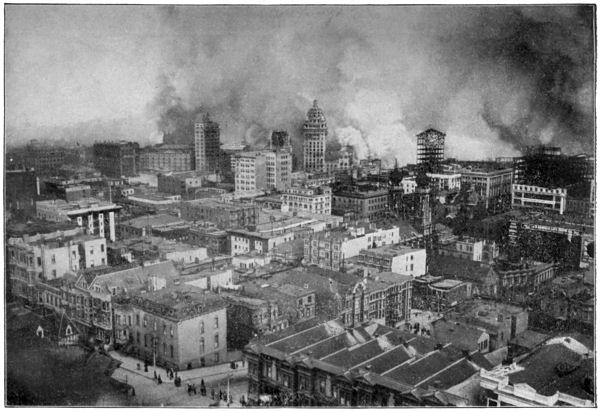

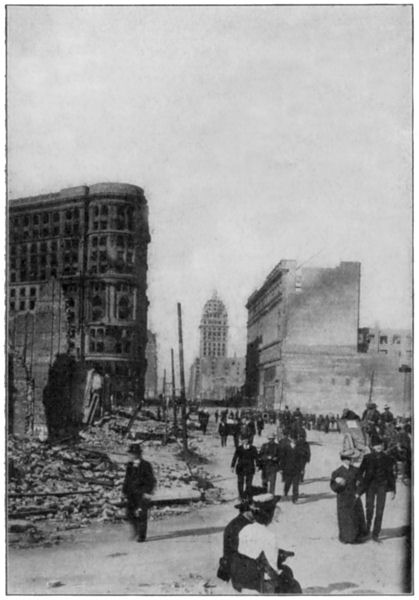

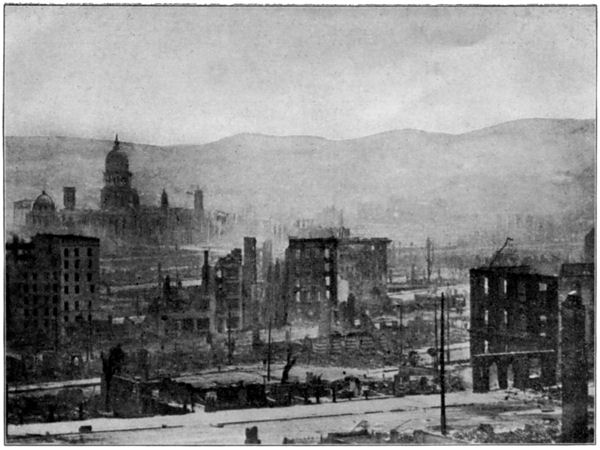

A PANORAMA OF THE RUINS.

Photographed from Nob Hill—City Hall at the left.

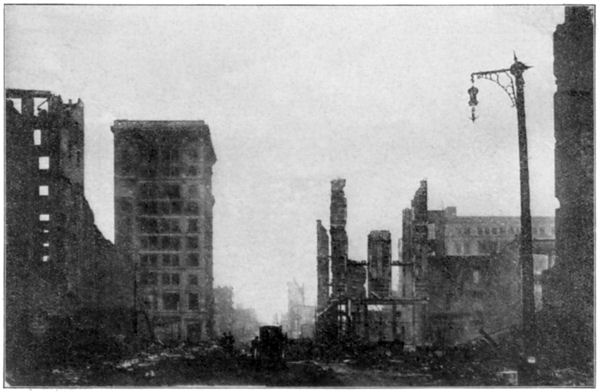

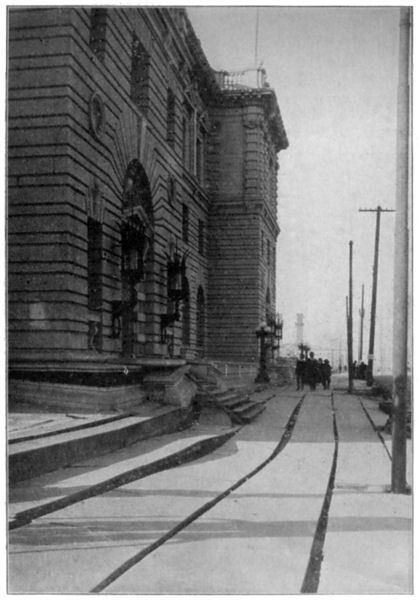

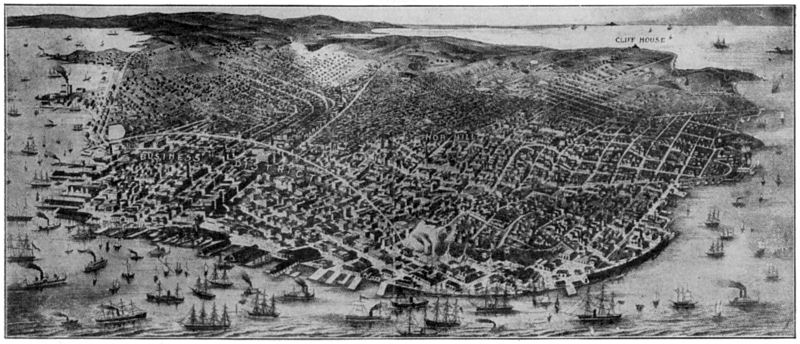

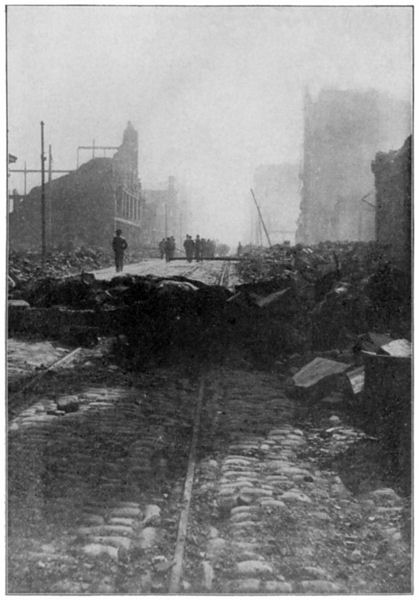

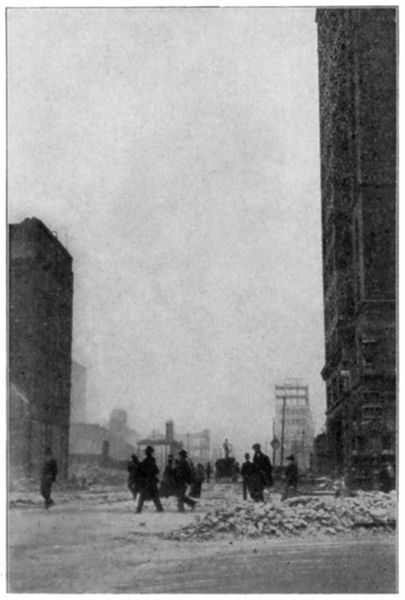

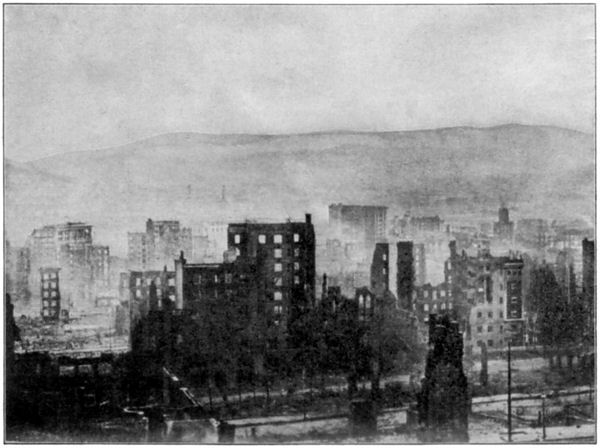

BUSINESS DISTRICT IN SAN FRANCISCO.

View from Nob Hill.

—————

Copyright 1906

BY

HUBERT D. RUSSELL

—————

PREFACE

IN PRESENTING this history of the San Francisco Earthquake Horror and Conflagration to the public, the publishers can assure the reader that it is the most complete and authentic history of the great disaster published.

The publishers set out with the determination to produce a work that would leave no room for any other history on this subject, a task for which they had the best facilities and the most perfect equipment.

The question of cost was not taken into consideration. The publishers wanted the best writers, the best illustrations, the best paper, printing and binding and proceeded immediately to get them. The services of the two best historical writers in the United States were secured within an hour after the first news of the catastrophe was received. The names and historical works of Richard Linthicum and Trumbull White are known in every household in the United States where current history is read. They are the authors of many standard works, including histories of recent wars and books of permanent reference, and rank among the world’s greatest descriptive writers.

A large staff of photographers have supplied illustrations for this great historical work depicting every phase of the catastrophe from the first shock of earthquake to the final work of relief. These illustrations have special interest and value because they are made from actual photographs taken by trained and skilled photographers. This history of the most recent of the world’s great disasters is beyond all comparison the most sumptuously and completely illustrated of any publication on this subject. So [Pg 8]numerous are the illustrations and so accurately do they portray every detail of the quake and fire that they constitute in themselves a complete, graphic and comprehensive pictorial history of the great catastrophe.

The story as told by the authors, however, is one of absorbing interest that thrills the reader with emotion and depicts the scenes of terror, destruction, misery and suffering as vividly as if the reader were an eye-witness to all the details of the stupendous disaster.

The history of the Earthquake and Fire Horror is told consecutively and systematically from beginning to end.

“The Doomed City” is a pen picture of San Francisco while its destruction was impending.

The four days of the conflagration are described each in separate chapters in such a way that the reader can follow the progress of the fire from the time of the first alarm until it was conquered by the dynamite squad of heroes.

A great amount of space has been devoted to “Thrilling Personal Experiences” and “Scenes of Death and Terror,” so that the reader has a thousand and one phases of the horror as witnessed by those who passed through the awful experience of the earthquake shock and the ordeal of the conflagration.

For purposes of comparison a chapter has been devoted to a magnificent description of San Francisco before the fire, “The City of a Hundred Hills,” the Mecca of sight-seers and pleasure loving travelers.

The descriptions of the Refuge Camps established in Golden Gate Park, the Presidio and other open spaces depict the sorrow and the suffering of the stricken people in words that appeal to the heart.

The magnificent manner in which the whole nation responded with aid and the conduct of the relief work are told in a way that brings a thrill of pride to every American heart.

“Fighting the Fire with Dynamite” is a thrilling chapter of [Pg 9]personal bravery and heroism, and the work of the “Boys in Blue” who patrolled the city and guarded life and property is adequately narrated.

Chinatown in San Francisco was one of the sights of the world and was visited by practically every tourist that passed through the Golden Gate. That odd corner of Cathay which was converted into a roaring furnace and completely consumed is described with breathless interest.

The “Ruin and Havoc in Other Coast Cities” describes the destruction of the great Leland Stanford, Jr., University, the scenes of horror and death at the State Asylum which collapsed, and in other ruined cities of the Pacific coast.

“The Earthquake as Viewed by Scientists” is a valuable addition to the seismology of the world—a science that is too little known, but which possesses tremendous interest for everyone.

The threatened destruction of Naples by the volcano of Vesuvius preceding the San Francisco disaster is fully described. The chapters on Vesuvius are especially valuable and interesting, by reason of the scientific belief that the two disasters are intimately related.

Altogether this volume is the best and most complete history of all the great disasters of the world and one that should be in the hands of every intelligent citizen, both as a historical and reference volume.

THE PUBLISHERS.

CONTENTS

| Preface | 7 |

| Introduction | 21 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE DOOMED CITY. | |

| Earthquake Begins the Wreck of San Francisco and a Conflagration without Parallel Completes the Work of Destruction—Tremendous Loss of Life in Quake and Fire—Property Loss $200,000,000 | 33 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| SAN FRANCISCO A ROARING FURNACE. | |

| Flames Spread in a Hundred Directions and the Fire Becomes the Greatest Conflagration of Modern Times—Entire Business Section and Fairest Part of Residence District Wiped Off the Map—Palaces of Millionaires Vanish in Flames or are Blown Up by Dynamite—The Worst Day of the Catastrophe | 46 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THIRD DAY ADDS TO HORROR. | |

| Fire Spreads North and South Attended by Many Spectacular Features—Heroic Work of Soldiers Under General Funston—Explosions of Gas Add to General Terror | 57 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| TWENTY SQUARE MILES OF WRECK AND RUIN. | |

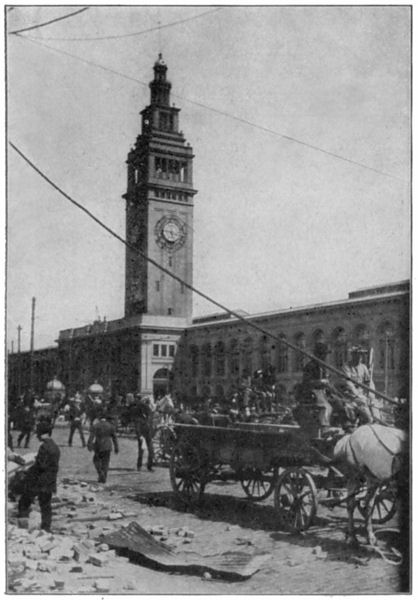

| Fierce Battle to Save the Famous Ferry Station, the Chief Inlet to and Egress from San Francisco—Fire Tugs and Vessels in the Bay Aid in Heroic Fight—Fort Mason, General Funston’s Temporary Headquarters, has Narrow Escape—A Survey of the Scene of Desolation | 69 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE CITY OF A HUNDRED HILLS. | |

| A Description of San Francisco, the Metropolis of the Pacific Coast, Before the Fire—One of the Most Beautiful and Picturesque Cities in America—Home of the California Bonanza Kings | 78 |

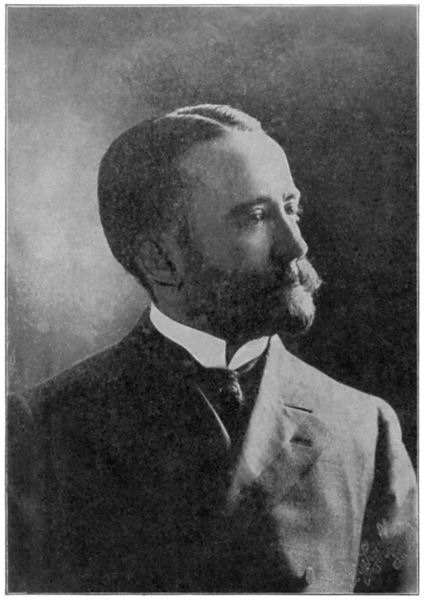

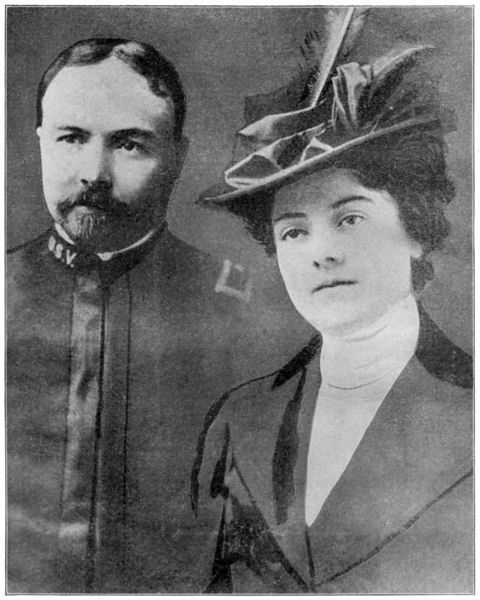

JAMES D. PHELAN.

Former Mayor of San Francisco, and who gave $1,000,000 for the relief of the sufferers. Largest sum given by an individual.

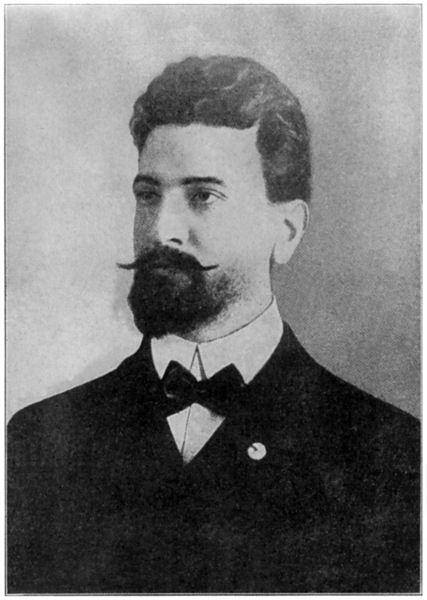

EUGENE E. SCHMITZ.

Mayor of San Francisco and who rendered great assistance in bringing order out of chaos.

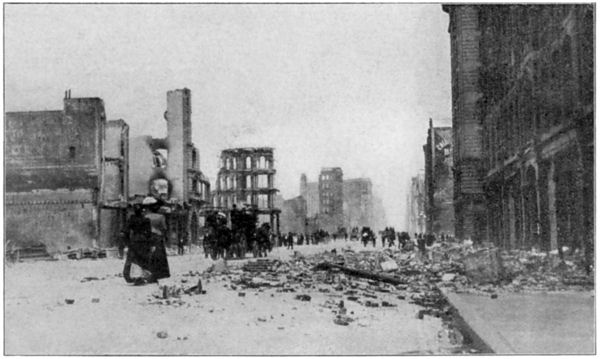

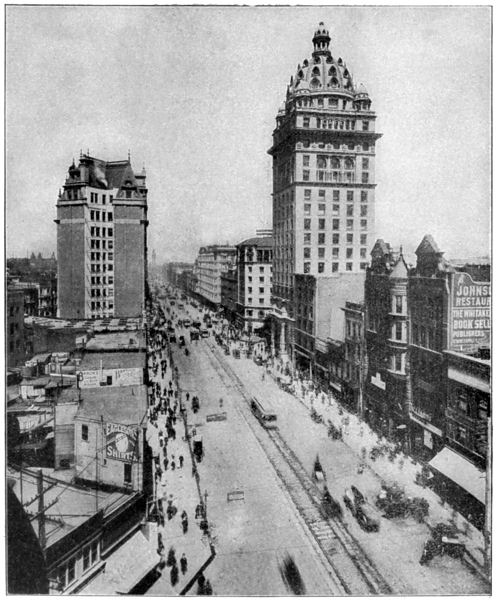

LOOKING EAST ON MARKET STREET.

VIEW FROM FIFTH AND MARKET STREETS.

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| SCENES OF TERROR, DEATH AND HEROISM. | |

| Thrilling Escapes and Deeds of Daring—Sublime Bravery and Self-Sacrifice by Men and Women—How the United States Mint and the Treasuries Were Saved and Protected by Devoted Employes and Soldiers—Pathetic Street Incidents—Soldiers and Police Compel Fashionably Attired to Assist in Cleaning Streets—Italians Drench Homes with Wine | 103 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THRILLING PERSONAL EXPERIENCES. | |

| Scenes of Horror and Panic Described by Victims of the Quake Who Escaped—How Helpless People Were Crushed to Death by Falling Buildings and Debris—Some Marvelous Escapes | 119 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THRILLING PERSONAL EXPERIENCES—CONTINUED. | |

| Hairbreadth Escapes from the Hotels Whose Walls Crumbled—Frantic Mothers Seek Children from Whom They Were Torn by the Quake—Reckless Use of Firearms by Cadet Militia—Tales of Heroism and Suffering | 132 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THROUGH LANES OF MISERY. | |

| A Graphic Pen Picture of San Francisco in Flames and in Ruins—Scenes and Stories of Human Interest where Millionaires and Paupers Mingled in a Common Brotherhood—A Harrowing Trip in an Automobile | 141 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| WHOLE NATION RESPONDS WITH AID. | |

| Government Appropriates Millions and Chicago Leads All Other Cities with a Round Million of Dollars—People in All Ranks of Life from President Roosevelt to the Humblest Wage Earner Give Promptly and Freely | 157 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| ALL CO-OPERATE IN RELIEF WORK. | |

| Citizens’ Committee Takes Charge of the Distribution of Supplies, Aided by the Red Cross Society and the Army—Nearly Three-Fourths of the Entire Population Fed and Sheltered in Refuge Camps | 162 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| OUR BOYS IN BLUE PROVE HEROISM. | |

| United States Troops at the Presidio and Fort Mason Under Command of General [Pg 14]Funston Bring Order Out of Chaos and Save City from Pestilence—San Francisco Said “Thank God for the Boys in Blue”—Stricken City Patrolled by Soldiers | 171 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

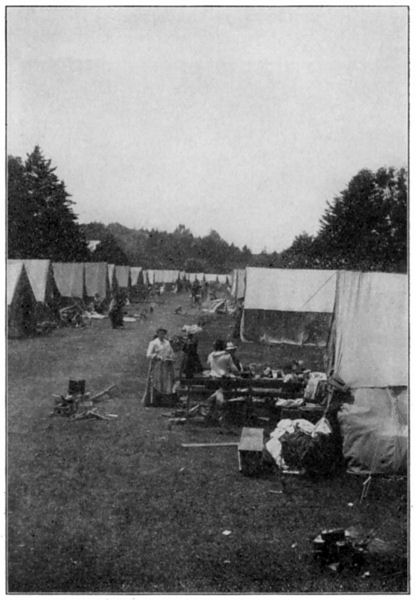

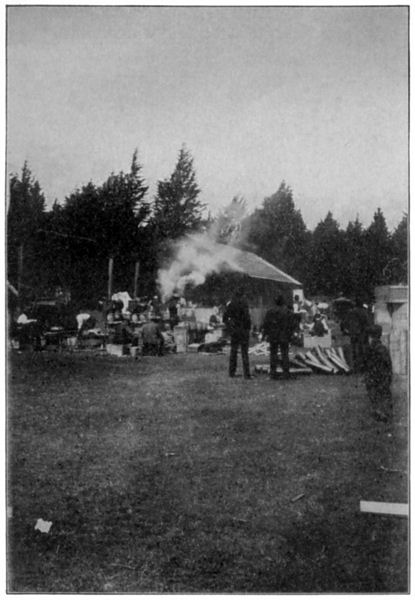

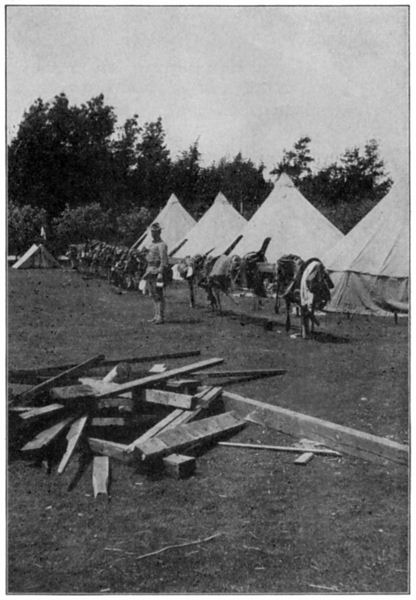

| IN THE REFUGE CAMPS. | |

| Scenes of Destitution in the Parks Where the Homeless Were Gathered—Rich and Poor Share Food and Bed Alike—All Distinctions of Wealth and Social Position Wiped Out by the Great Calamity | 178 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| RUINS AND HAVOC IN COAST CITIES. | |

| San Jose, the Prettiest Place in the State, Wrecked by Quake—State Insane Asylum Collapsed and Buried Many Patients Beneath the Crumbled Walls—Enormous Damage at Santa Rosa | 189 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

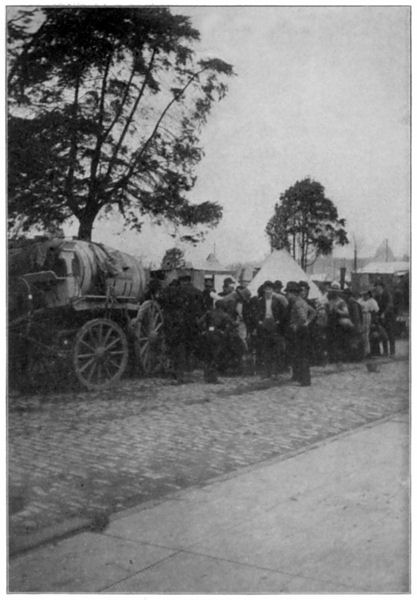

| DESTRUCTION OF GREAT STANFORD UNIVERSITY. | |

| California’s Magnificent Educational Institution, the Pride of the State, Wrecked by Quake—Founded by the Late Senator Leland Stanford as a Memorial to His Son and Namesake—Loss $3,000,000 | 198 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| FIGHTING FIRE WITH DYNAMITE. | |

| San Francisco Conflagration Eventually Checked by the Use of Explosives—Lesson of Baltimore Needed in Coast City—Western Remnant of City in Residence Section Saved by Blowing Up Beautiful Homes of the Rich | 208 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| MISCELLANEOUS FACTS AND INCIDENTS. | |

| Many Babies Born in Refuge Camps—Expressions of Sympathy from Foreign Nations—San Francisco’s Famous Restaurants—Plight of Newspaper and Telegraph Offices | 214 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| DISASTER AS VIEWED BY SCIENTISTS. | |

| Scientists are Divided Upon the Theories Concerning the Shock That Wrought Havoc in the Golden Gate City—May Have Originated Miles Under the Ocean—Growth of the Sierra Madre Mountains May Have Been the Cause | 230 |

| [Pg 15]CHAPTER XIX. | |

| CHINATOWN, A PLAGUE SPOT BLOTTED OUT. | |

| An Oriental Hell within an American City—Foreign in Its Stores, Gambling Dens and Inhabitants—The Mecca of All San Francisco Sight Seers—Secret Passages, Opium Joints and Slave Trade Its Chief Features | 246 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| THE NEW SAN FRANCISCO. | |

| A Modern City of Steel on the Ruins of the City that Was—A Beautiful Vista of Boulevards, Parks and Open Spaces Flanked by the Massive Structures of Commerce and the Palaces of Wealth and Fashion | 255 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| VESUVIUS THREATENS NAPLES. | |

| Beautiful Italian City on the Mediterranean Almost Engulfed in Ashes and Lava from the Terrible Volcano—Worst Eruption Since the Days of Pompeii and Herculaneum—Buildings Crushed and Thousands Rendered Homeless | 267 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| SCENES IN FRIGHTENED NAPLES. | |

| Blistering Showers of Hot Ashes—The People Frantic—Cry Everywhere “When Will It End?”—Atmosphere Charged with Electricity and Poisonous Fumes | 279 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| VOLCANOES AND EARTHQUAKES EXPLAINED. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| The Theories of Science on Seismic Convulsions—Volcanoes Likened to Boils on the Human Body, Through Which the Fires and Impurities of the Blood Manifest Themselves—Seepage of Ocean Waters Through Crevices in the Rocks Reaches the Internal Fires of the Earth—Steam Is Generated and an Explosion Follows—Geysers and Steam Boilers as Illustrations—Views of the World’s Most Eminent Scientists Concerning the Causes of the Eruptions of Mount Pelee and La Soufriere | 285 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| TERRIBLE VOLCANIC DISASTERS OF THE PAST. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Destruction of Sodom, Gomorrah and the Other Cities of the Plain—The Bible Account a Graphic Description of the Event—Ancient Writers Tell of Earthquakes and Volcanoes of Antiquity—Discovery of Buried Cities of Which No Records Remain—Formation of the Dead Sea—The Valley of the Jordan and Its Physical Characteristics | 303 |

| [Pg 16]CHAPTER XXV. | |

| VESUVIUS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF POMPEII. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Most Famous Volcanic Eruption in History—Roman Cities Overwhelmed—Scenes of Horror Described by Pliny, the Great Classic Writer, an Eye-Witness of the Disaster—Buried in Ashes and Lava—The Stricken Towns Preserved for Centuries Excavated in Modern Times as a Wonderful Museum of the Life of 1,800 Years Ago | 309 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| MOUNT ÆTNA AND THE SICILIAN HORRORS. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| A Volcano with a Record of Twenty-five Centuries—Seventy-eight Recorded Eruptions—Three Hundred Thousand Inhabitants Dwelling on the Slopes of the Mountain and in the Valleys at Its Base—Stories of Earthquake Shocks and Lava Flows—Tales of Destruction—Described by Ancient and Modern Writers and Eye-Witnesses | 321 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| LISBON EARTHQUAKE SCOURGED. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Sixty Thousand Lives Lost in a Few Moments—An Opulent and Populous Capital Destroyed—Graphic Account by an English Merchant Who Resided in the Stricken City—Tidal Waves Drown Thousands in the City Streets—Ships Engulfed in the Harbor—Criminals Rob and Burn—Terrible Desolation and Suffering | 334 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| JAPAN AND ITS DISASTROUS EARTHQUAKES AND VOLCANOES. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| The Island Empire Subject to Convulsions of Nature—Legends of Ancient Disturbances—Famous Volcano of Fuji-yama Formed in One Night—More Than One Hundred Volcanoes in Japan—Two Hundred and Thirty-two Eruptions Recorded—Devastation of Thriving Towns and Busy Cities—The Capital a Sufferer—Scenes of Desolation after the Most Recent Great Earthquakes | 344 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| KRAKATOA, THE GREATEST OF VOLCANIC EXPLOSIONS. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| East Indian Catastrophes—The Volcano that Blew Its Own Head Off—The Terrific Crash Heard Three Thousand Miles—Atmospheric Waves Travel Seven Times Around the Earth—A Pillar of Dust Seventeen Miles High—Islands of the Malay Archipelago Blotted Out of Existence—Native Villages Annihilated—Other Disastrous Upheavals in the East Indies | 353 |

| [Pg 17]CHAPTER XXX. | |

| OUR GREAT HAWAIIAN AND ALASKAN VOLCANOES. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Greatest Volcanoes in the World Are Under the American Flag—Huge Craters in Our Pacific Islands—Native Worship of the Gods of the Flaming Mountains—Eruptions of the Past—Heroic Defiance of Pele, the Goddess of Volcanoes by a Brave Hawaiian Queen—The Spell of Superstition Broken—Volcanic Peaks in Alaska, Our Northern Territory—Aleutian Islands Report Eruptions | 363 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| SOUTH AMERICAN CITIES DESTROYED. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Earthquakes Ravage the Coast Cities of Peru and the Neighboring Countries—Spanish Capitals in the New World Frequent Sufferers—Lima, Callao and Caracas Devastated—Tidal Waves Accompany the Earthquakes—Juan Fernandez Island Shaken—Fissures Engulf Men and Animals—Peculiar Effects Observed | 373 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| EARTHQUAKES AND VOLCANOES IN CENTRAL AMERICA AND MEXICO. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| A Region Frequently Disturbed by Subterranean Forces—Guatemala a Fated City—A Lake Eruption in Honduras Described by a Great Painter—City of San Jose Destroyed—Inhabitants Leave the Vicinity to Wander as Beggars—Disturbances on the Route of the Proposed Nicaragua Canal—San Salvador Is Shaken—Mexican Cities Suffer | 382 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| CHARLESTON, GALVESTON, JOHNSTOWN—OUR AMERICAN DISASTERS. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Earthquake Shock in South Carolina—Many Lives Lost in the Riven City—Galveston Smitten by Tidal Wave and Hurricane—Thousands Die in Flood and Shattered Buildings—The Gulf Coast Desolated—Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Swept by Water from a Bursting Reservoir—Scenes of Horror | 389 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| ST. PIERRE, MARTINIQUE, ANNIHILATED BY A VOLCANO. | |

| BY TRUMBULL WHITE. | |

| Fifty Thousand Men, Women and Children Slain in an Instant—Molten Fire and Suffocating Gases Rob Multitudes of Life—Death Reigns in the Streets of the Stricken City—The Governor and Foreign Consuls Die at Their Posts of Duty—No Escape for the Hapless Residents in the Fated Town—Scenes of Suffering Described—Desolation Over All—Few Left to Tell the Tale of the Morning of Disaster | 397 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The Awful Horror of an Earthquake | Frontispiece |

| A Panorama of the Ruins | Frontispiece |

| Business District of San Francisco | Frontispiece |

| Former Mayor James D. Phelan | 11 |

| Mayor Eugene E. Schmitz | 11 |

| Looking East on Market Street | 12 |

| View from Fifth and Market Streets | 12 |

| Market Street, Scene of Ruins | 31 |

| United States Guards in Charge of Dead | 32 |

| Street Torn Up by Earthquake | 41 |

| Stockton Street | 42 |

| Grant Avenue | 42 |

| Mission Street | 43 |

| O’Farrell Street | 43 |

| Looking North from Sixth and Market Streets | 44 |

| The Orpheum Theatre | 44 |

| San Francisco on Fire | 53 |

| Destroyed Wholesale Houses | 54 |

| Cracks in Earth | 63 |

| Ruins of Emporium Building | 63 |

| Map—Bird’s-Eye View of San Francisco | 64 |

| Ruins of Hall of Justice | 65 |

| Looking Down Market Toward Call Building | 66 |

| From California Street Toward Call Building | 66 |

| Market Street Before the Disaster | 75 |

| The Devouring Flames | 76 |

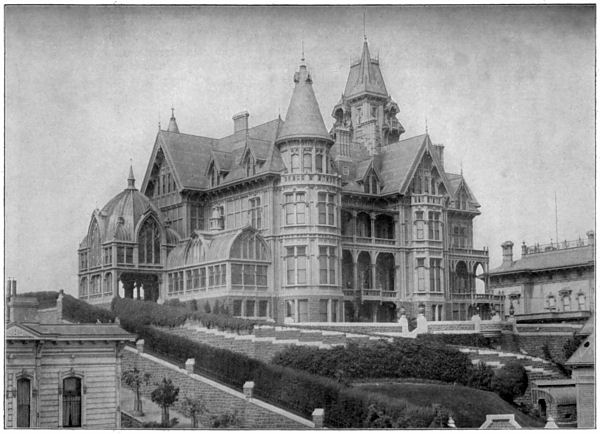

| Mark Hopkins Institute, Nob Hill | 85 |

| United States Mint | 86 |

| New Postoffice Building | 87 |

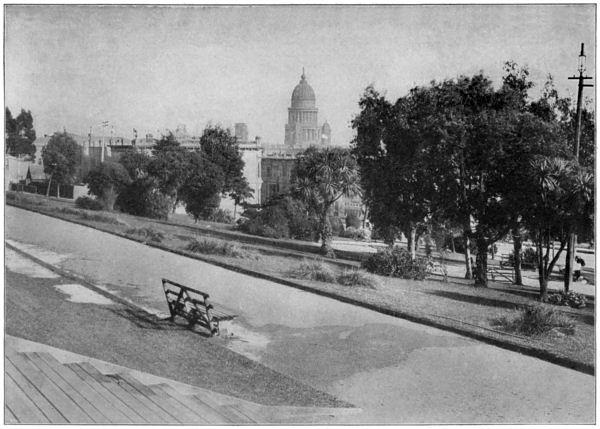

| Jefferson Square | 88 |

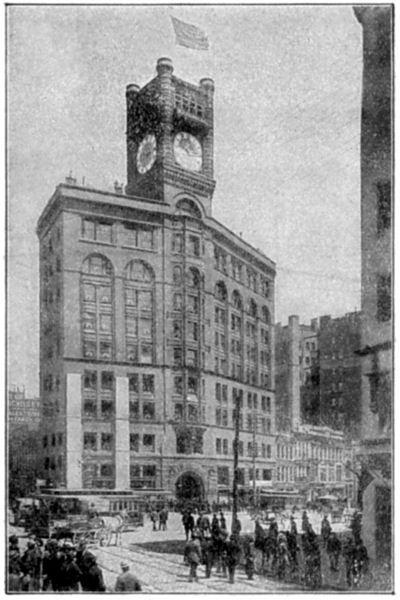

| Chronicle Building | 97 |

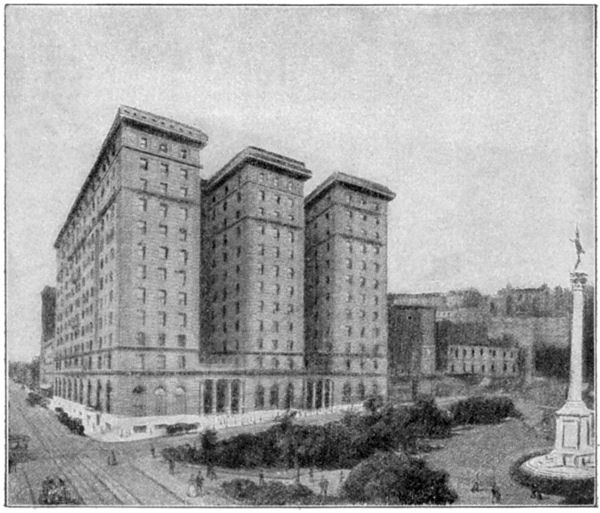

| St. Francis Hotel (Before the Earthquake) | 97 |

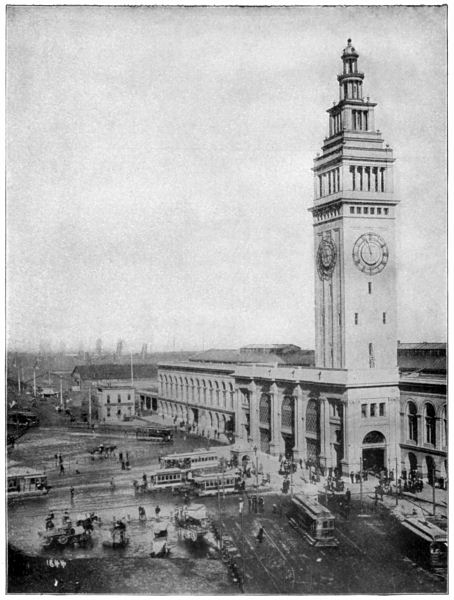

| Ferry House | 98 |

| Free Water | 115 |

| Distributing Clothes | 115 |

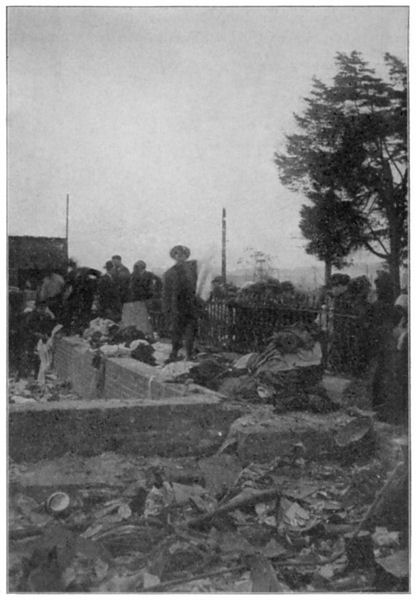

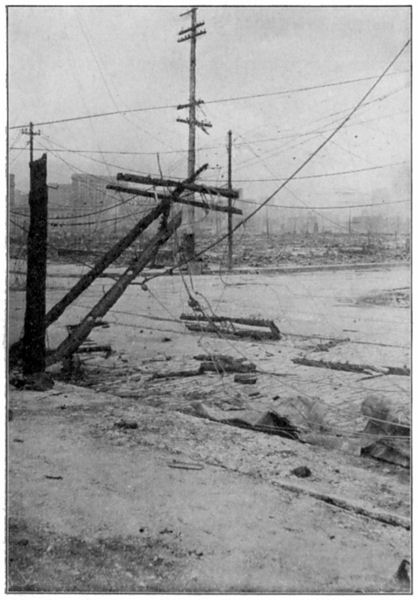

| [Pg 19]Wires Destroyed | 116 |

| Military Camp | 116 |

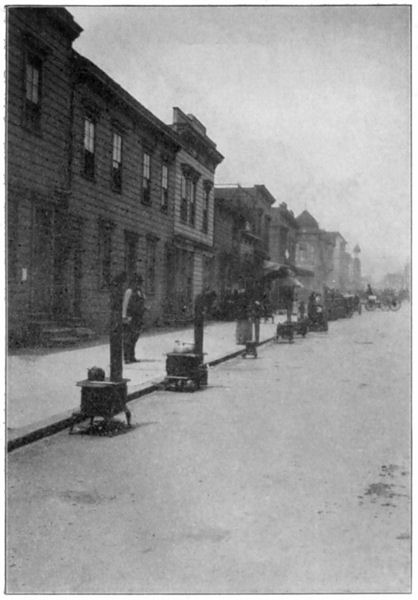

| Kitchens in the Street | 133 |

| Wing of City Hall, Crumbled | 133 |

| Cattle Killed | 134 |

| St. John’s Church, Ruined | 134 |

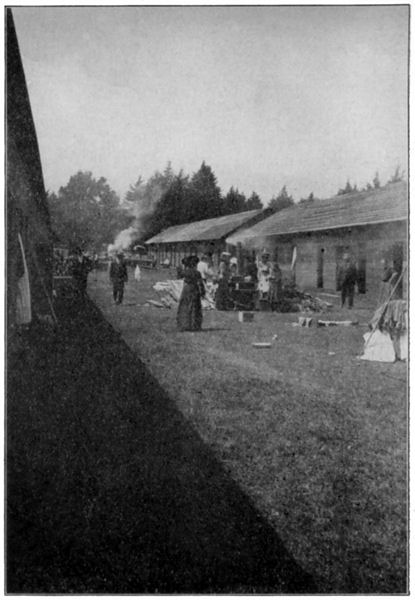

| Camp Kitchen in Ball Park | 151 |

| Shacks in Golden Gate Park | 151 |

| Governor Pardee | 152 |

| Major General Adolphus Greely | 152 |

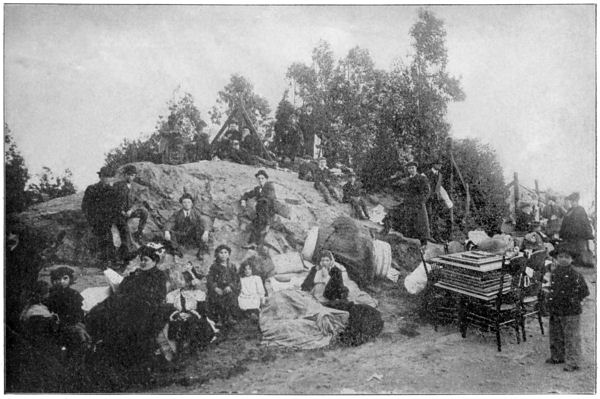

| Refugees on Telegraph Hill | 169 |

| General Funston and Wife | 170 |

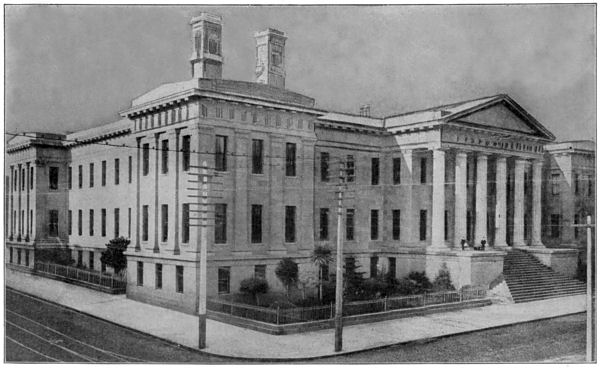

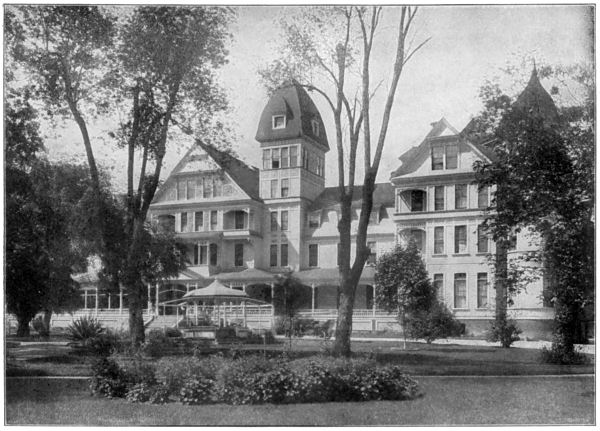

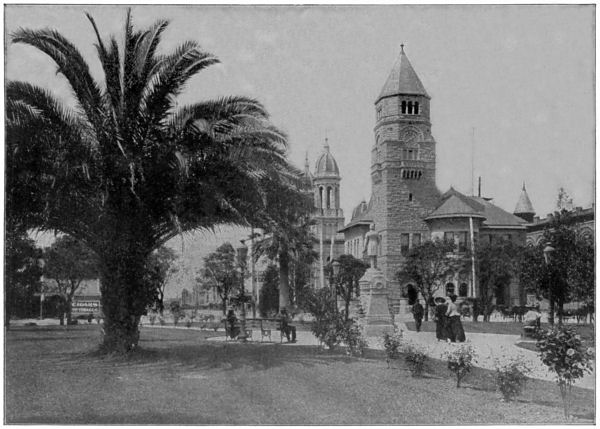

| Vendome Hotel, San Jose | 187 |

| Postoffice, San Jose | 188 |

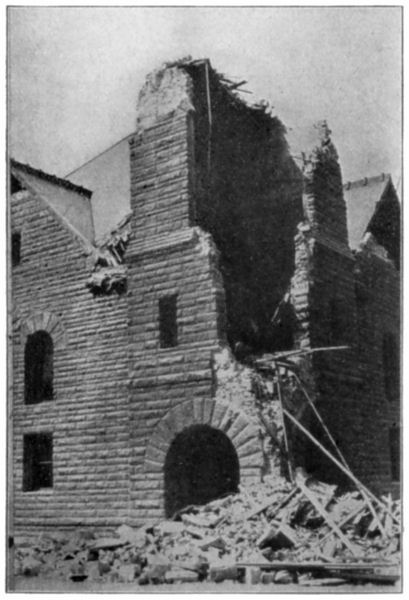

| Corner of Baptist Church | 205 |

| Kearney Street, San Francisco | 205 |

| Ferry Building | 206 |

| Military Quarters | 206 |

| Randolph Storage | 223 |

| Switchboard Destroyed | 223 |

| St. Dominici Church, Freak with Steeple | 224 |

| St. Dominici Church, Wrecked | 224 |

| Chinese Refugees | 241 |

| Flat Building, Sunk | 242 |

| Seeking Lost Friends | 259 |

| All that Was Left of a Fine Residence | 259 |

| Soldiers’ Encampment | 260 |

| Alameda Park | 260 |

| Dolores Mission | 277 |

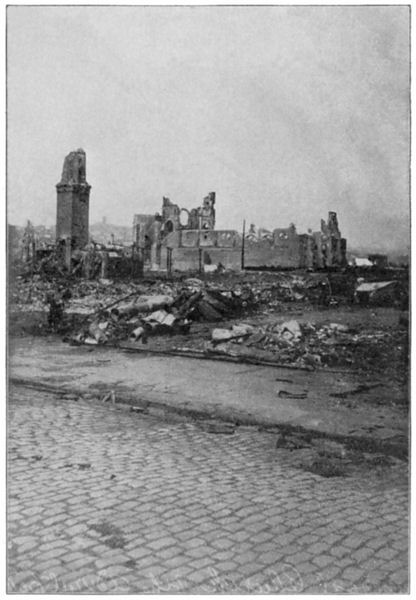

| Wreck and Ruin | 278 |

| Wreck and Ruin | 278 |

| Crack in Earth | 295 |

| Ghoulish Thieves Looting the Dead | 296 |

| Effect of Earthquake on Modern Steel Building | 313 |

| Vesuvius During Recent Eruption | 314 |

| Road Leading to Vesuvius Before Eruption | 314 |

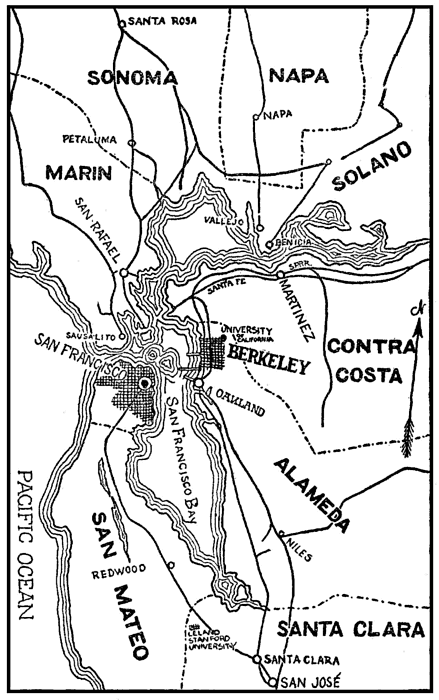

MAP OF SAN FRANCISCO AND VICINITY.

Showing towns and section of country that suffered the most from effects of earthquake.

INTRODUCTION

By the RT. REV. SAMUEL FALLOWS, D. D., LL. D.

ABRIGHT, intelligent unbeliever in the Providential government of the world has just said to me in discussing this greatest of calamities which has occurred in our nation’s history, “Where is your benevolent God?” I answered “He still lives and guides the affairs of men.” Another said, “The preachers would do well not to meddle with the subject.” But the reply was made, “It is precisely the subject with which they, more than others, should concern themselves.”

It is for them, when the hearts of men are failing to confidently proclaim that God has not abdicated his throne, and that man is not the sport of malign and lawless forces.

All events are ordered for the best; and the evils which we suffer are parts of a great movement conducted by Almighty power, under the direction of Infinite Wisdom and Goodness. God’s creation is a perfect work. The world in which we live is the best possible world on the whole; not the best possible to the individual at any given moment, but the best possible on the whole, all creatures considered and all the ages of man taken into the account. This is the affirmation of a triumphant optimism.

John Stuart Mill averred that a better world could have been made and more favorable conditions for man devised. But before this hypothesis can be sustained, the skeptic from the beginning of time must have scanned the history of every individual and studied it in its minutest details. He must have explored every rill and river of influence entering into his character. He must have understood every relation of the individual to every other [Pg 22]person through all the ages. He must have mastered all the facts and laws of our earth. And as it sustains a vital connection with the solar system, he must have grasped all the mysteries which are involved in it.

As this system is related to the still grander one of which it is a part, he must have known the law and workings of its every star and sun. Still more, he must have gone from system to system with their millions of worlds and become familiar with every part of the vast stupendous whole. He must have learned every secret of all Nature’s forces, and have penetrated into the interior recesses of the Divine Being. He must have taken the place of God Himself.

A Divine Providence.

Amid all our doubts and distresses we must hold fast to the belief that there is a God who maketh the clouds His chariot and walketh upon the wings of the wind—a God who is present in every summer breath and every wintry blast, in every budding leaf, and every opening flower, in the fall of every sparrow and the wheeling of every world. His Providence is in every swinging of the tides, in every circulation of the air, in all attractions and repulsions, in all cohesions and gravitations. These, and the varied phenomena of nature are the direct expressions of the Divine Energy, the modes of operation of the Divine Mind, the manifestations of the Divine Wisdom and the expressions of the Divine Love.

The very thunderbolt that rives the oak and by its shock sunders the soul from the body of some unfortunate one purifies the air that millions may breathe the breath of life.

The very earthquake which shakes the earth to its center and shatters cities into ruin, prevents by that very concussion the graver catastrophes which bury continents out of sight.

The very hurricane which comes sweeping down and on, [Pg 23]prostrating forests, hurling mighty tidal waves on the shore and sending down many a gallant ship with all its crew, bears on its destructive wings, “the incense of the sea,” to remotest parts, that there may be the blooming of flowers, the upspringing of grass, the waving of all the banners of green, and the carrying away of the vapors of death that spring from decaying mold.

Man the Conqueror.

Pascal said “man is but a reed, the feeblest thing in nature, but he is a reed that thinks.” The elemental forces break loose and for the time being he cannot control them. Amid nature’s convulsions he is utterly helpless and insignificant.

It is but for a moment, however, that he yields. He knows that he is the central figure in the universe of worlds. “He is not one part of the furniture of this planet, not the highest merely in the scale of its creatures but the lord of all.” He is not a parasite but the paragon of the globe. He has faith in the unchangeableness of the laws he is mastering while suffering from them. He confidently declares there is nothing fitful, nothing capricious, nothing irregular in their action. The greater the calamity the more earnest his effort to ascertain its causes and learn the lessons it teaches.

Fearlessly man must meet the events of life as they come. Speculations as to future cataclysms and fearful forebodings as to the immediate end of the world must all be given to the winds. There will be at some time an end to our globe. It may be frozen out, or burned out, or scattered into impalpable dust by the terrific explosion of steam generated by an ocean of water precipitated into an ocean of fire. But cycles of millenniums will intervene before such an apocalypse takes place.

In the spirit of Campbell’s “Last Man” we must live, and act;

“Go sun, while mercy holds me upOn nature’s awful waste[Pg 24]To taste the last and bitter cupOf death, that man must taste:Go, say thou saw’st the last of Adam’s raceOn earth’s sepulchral clod,The darkening Universe defy,To quench his immortalityOr shake his trust in God.”

Wickedness not the Cause of Destruction.

There are among us men who seem to suppose that they have been let into the counsels of the Almighty and have the right to aver that this calamity so colossal in its proportions and awful in its character is a judgment upon our sister city for its great wickedness. I heard similar declarations when Chicago was swept by its tornado of flame. Neither Chicago nor San Francisco could claim to be pre-eminent in righteousness, but, that Divine Providence should visit the vials of His wrath in an especial manner upon them because of their iniquity, is utterly repugnant both to reason and Holy Scripture. Only by a special revelation from the Most High, accompanied with evidence corresponding to that which substantiates the claims of an Old Testament prophet can any warrant be given to any man to declare that a great catastrophe is the consequence of the moral sins of a given community.

The Book of Job gives the emphatic denial to the claim that specific human misery and suffering are the sure signs of the retribution for specific guilt or sin. The Great Teacher and Divine Savior of men reaffirmed the truth of the teachings of that ancient poem by asserting that the man born blind was not thus grievously afflicted because he himself or his parents had been guilty of some peculiar iniquity. He declared that the eighteen persons who had been killed by the falling of the Tower of Siloam (probably from an earthquake shock), were not greater sinners than those who were hearing him speak.

The Unity of Humanity.

This great disaster has given a new emphasis to our National Unity. Congress for the first time has voted to aid directly a city in distress within the bounds of our country. State Legislatures have followed its example, while municipal organizations by the score have poured out their benefactions.

From all quarters of the civilized globe expressions of sympathy have come and tenders of help made, without parallel in the annals of time.

All this has revealed the essential oneness of Humanity. It has shown that beneath all the artificial distinctions of society man is the equal of his fellow man. All the barriers of nationality, creed, color, social position, riches, poverty have been broken down in the common sufferings of the stricken people on our Western Coast. The chord of brotherhood is vibrating in all our hearts. Its divine melodies are heard above the roar and rush of business in our streets. We have been amassing wealth too often selfishly, and madly. We have been making money our god; and now we see how vain a thing it is in which to put our trust. Now we feel “it is more blessed to give than to receive.” Now, kindness and tenderness melt the hardness of our natures. Now, as we stretch the helping hand and witness the joy and gratitude evoked, by our God-like deeds, we feel in every fiber of our being the thrill of the poet’s rapt exclamation:

“O, if there be an Elysium on earthIt is this, it is this.”

Recovery from Earthquakes.

Earthquakes throughout the world have not disturbed the ultimate confidence of man in the stability of this old and often seemingly wayward earth. All Greece was convulsed centuries ago from center to circumference and Constantinople for the second time was overturned with the loss of tens of thousands of lives. [Pg 26]Five hundred years afterwards the city was again shaken and a large number of its buildings destroyed with an appalling loss of life. Again and again was the ancient city of Antioch shattered in almost every portion but each time she arose stronger than before. Fifteen hundred years ago one mighty shock cost the lives of 250,000 of its people, but Antioch remains, although its grandeur from other causes has departed. Twice at least has Naples been partly destroyed along with its neighboring towns and more than 100,000 people have perished. But Naples is still on the map of the earth.

Lisbon, one hundred and fifty years ago lost 50,000 of its inhabitants and had a part of its territory suddenly submerged under 600 feet of water. For 5,000 miles the earthquake extended and shook Scotland itself, alarming the English people and causing fasting and prayer and special sermons in the Scotch and Anglican churches.

Two hundred years ago Tokio was almost entirely destroyed. Every building was practically in ruins and more than 200,000 were numbered among its mangled dead. Again in 1855 it nearly suffered a similar fate with a decreased though very large loss of life. But Tokio has helped Japan play its dramatic part in the recent history of the world.

Graphic descriptions have been left us by eye witnesses of the tremendous upheaval in the great Mississippi Valley in 1811, when the flow of the mighty river was stopped, and the land on its banks for vast distances from its current was sunk for a stretch of nearly 300 miles. But the Father of Waters still goes on unvexed to the sea.

Charleston was sadly shaken twenty years ago, but her streets are not deserted. Senator Tillman still speaks vigorously as the representative of her wide-awake and increasing population.

Some of us have not forgotten when we saw Chicago burning in 1871, the doubts and fears of our own hearts regarding the [Pg 27]future of our city. Jeremiads were oracularly and dolefully uttered by many a prophetic pessimist that Chicago would never be rebuilt, that it would be burned again if it should rise from its ashes. Well! it did rise. It was again sadly burned. It again arose. It has been rising and growing ever since. And it is now ready to send its millions of dollars and more if needed to the stricken cities on our Pacific coast.

Not in fear then, but in hope, must our homes, our churches, our schools, our manufactories, our marts of trade, our bank buildings, our office buildings and other needed structures be established.

San Francisco will be Rebuilt.

The prophets of evil may croak as dismally as they may desire and predict that the earth will again shudder and quake and imperil if not destroy any city man may attempt to create on the now dismantled and disfigured site. But San Francisco will as surely be rebuilt as the sun rises in heaven. No earthquake upheaval can shake the determined will of the unconquerable American to recover from disaster. It will simply serve to make him more rock-rooted and firm in his purpose to pluck victory from defeat. No fiery blasts can burn up the asbestos of his unconsumable energy. No disaster, however seemingly overwhelming, can daunt his faith or dim his hope, or prevent his progress.

San Francisco occupies the imperial gateway of the Pacific. Her harbor, one of the best in the world, still preserves its contour and extends its protecting arms as when Francis Drake found his way into it nearly four hundred years ago. The finger of Providence still points to it amid wreck and ruin and smoldering ashes as the place where a teeming city with every mark of a splendid civilization shall be the pride of our Western shores. Her wailing Miserere shall be turned into a joyful Te Deum.

Not for a moment after the temporary paralysis is past will [Pg 28]the work of reconstruction be delayed. We know not when another shock may come or whether it will come again at all. No matter. The city shall rise again. And with it, shall the other cities that have suffered from the earth’s commotion rise again into newness of life. California will not cease to be the land of fruits and flowers, of beauty and bounty, of sunshine and splendor from this temporary disturbance. It will continue to maintain its just reputation for all that is admirable in the American character, of pluck and perseverance, of vigor and versatility, and above all of the royal hospitality of its homes and of the welcome it always extends to every new and inspiring thought.

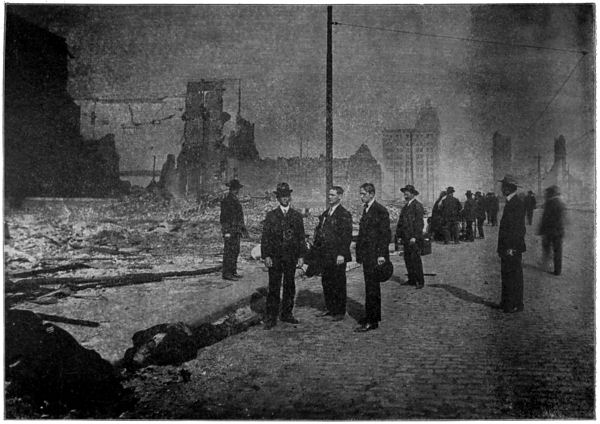

MARKET STREET SCENE OF RUINS.

Looking west on Market Street from 5th Street. The man in gutter was probably shot by the soldiers.

Copyright by R. L. Forrest 1906.

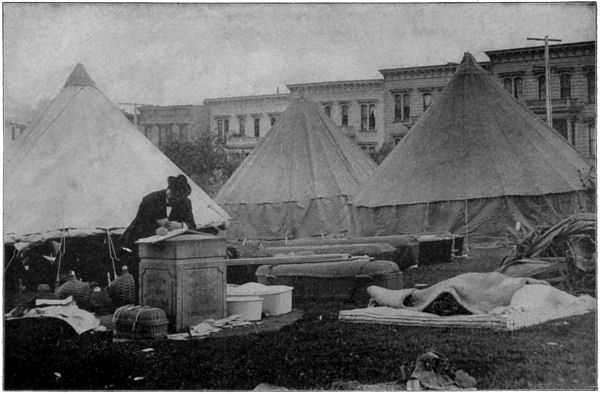

U. S. GUARDS IN CHARGE OF DEAD.

A scene in Jefferson Square where the U. S. Guards are caring for the dead. Note the caskets, dead person laid out on mattress, also guard tents, embalming fluids in demijohns, etc. Name or description of the dead being recorded.

CHAPTER I.

THE DOOMED CITY.

Earthquake Begins the Wreck of San Francisco and a Conflagration without Parallel Completes the Awful Work of Destruction—Tremendous Loss of life in Quake and Fire—Property Loss $200,000,000.

AFTER four days and three nights that have no parallel outside of Dante’s Inferno, the city of San Francisco, the American metropolis by the Golden Gate, was a mass of glowing embers fast resolving into heaps and winrows of grey ashes emblematic of devastation and death.

Where on the morning of April 18, 1906, stood a city of magnificent splendor, wealthier and more prosperous than Tyre and Sidon of antiquity, enriched by the mines of Ophir, there lay but a scene of desolation. The proud and beautiful city had been shorn of its manifold glories, its palaces and vast commercial emporiums levelled to the earth and its wide area of homes, where dwelt a happy and a prosperous people, lay prostrate in thin ashes. Here and there in the charred ruins and the streets lately blackened by waves of flame, lay crushed or charred corpses, unheeded by the survivors, some of whom were fighting desperately for their lives and property, while others were panic stricken and paralyzed by fear. Thousands of lives had been sacrificed and millions upon millions of dollars in property utterly destroyed.

The beginning of the unparalleled catastrophe was on the morning of April 18, 1906. In the grey dawn, when but few had arisen for the day, a shock of earthquake rocked the foundations of the city and precipitated scenes of panic and terror throughout the business and residence districts.

[Pg 34]It was 5:15 o’clock in the morning when the terrific earthquake shook San Francisco and the surrounding country. One shock apparently lasted two minutes and there was an almost immediate collapse of flimsy structures all over the former city. The water supply was cut off and when fires broke out in various sections there was nothing to do but to let the buildings burn. Telegraphic and telephone communication was shut off. Electric light and gas plants were rendered useless and the city was left without water, light or power. Street car tracks were twisted out of shape and even the ferry-boats ceased to run.

The dreadful earthquake shock came without warning, its motion apparently being from east to west. At first the upheaval of the earth was gradual, but in a few seconds it increased in intensity. Chimneys began to fall and buildings to crack, tottering on their foundations.

People became panic stricken and rushed into the streets, most of them in their night attire. They were met by showers of falling buildings, bricks, cornices and walls. Many were instantly crushed to death, while others were dreadfully mangled. Those who remained indoors generally escaped with their lives, though scores were hit by detached plaster, pictures and articles thrown to the floor by the shock.

Scarcely had the earth ceased to shake when fires broke out simultaneously in many places. The fire department promptly responded to the first calls for aid, but it was found that the water mains had been rendered useless by the underground movement. Fanned by a light breeze, the flames quickly spread and soon many blocks were seen to be doomed.

Then dynamite was resorted to and the sound of frequent explosions added to the terror of the people. All efforts to stay the progress of the fire, however, proved futile. The south side of Market street from Ninth street to the bay was soon ablaze, the fire covering a belt two blocks wide. On this, the main thoroughfare of the city, are located many of the finest edifices in the city, [Pg 35]including the Grant, Parrott, Flood, Call, Examiner and Monadnock buildings, the Palace and Grand hotels and numerous wholesale houses.

At the same time the commercial establishments and banks north of Market street were burning. The burning district in this section extended from Sansome street to the water front and from Market street to Broadway. Fires also broke out in the mission and the entire city seemed to be in flames.

The fire swept down the streets so rapidly that it was practically impossible to save anything in its way. It reached the Grand Opera House on Mission street and in a moment had burned through the roof. The Metropolitan opera company from New York had just opened its season there and all the expensive scenery and costumes were soon reduced to ashes. From the opera house the fire leaped from building to building, leveling them almost to the ground in quick succession.

The Call editorial and mechanical departments were totally destroyed in a few minutes and the flames leaped across Stevenson street toward the fine fifteen-story stone and iron Claus Spreckels building, which with its lofty dome is the most notable edifice in San Francisco. Two small wooden buildings furnished fuel to ignite the splendid pile.

Thousands of people watched the hungry tongues of flame licking the stone walls. At first no impression was made, but suddenly there was a cracking of glass and an entrance was affected. The interior furnishings of the fourth floor were the first to go. Then as though by magic, smoke issued from the top of the dome.

This was followed by a most spectacular illumination. The round windows of the dome shone like so many full moons; they burst and gave vent to long, waving streamers of flame. The crowd watched the spectacle with bated breath. One woman wrung her hands and burst into a torrent of tears.

“It is so terrible!” she sobbed. The tall and slender structure [Pg 36]which had withstood the forces of the earth appeared doomed to fall a prey to fire. After a while, however, the light grew less intense and the flames, finding nothing more to consume, gradually went, leaving the building standing but completely burned out.

The Palace Hotel, the rear of which was constantly threatened, was the scene of much excitement, the guests leaving in haste, many only with the clothing they wore. Finding that the hotel, being surrounded on all sides by streets, was likely to remain immune, many returned and made arrangements for the removal of their belongings, though little could be taken away owing to the utter absence of transportation facilities. The fire broke out anew and the building was soon a mass of ruins.

The Parrott building, in which were located the chambers of the state supreme court, the lower floors being devoted to an immense department store, was ruined, though its massive walls were not all destroyed.

A little farther down Market street the Academy of Sciences and the Jennie Flood building and the History building kindled and burned like tinder. Sparks carried across the wide street ignited the Phelan building and the army headquarters of the department of California, General Funston commanding, were burned.

Still nearing the bay, the waters of which did the firemen good service, along the docks, the fire took the Rialto building, a handsome skyscraper, and converted scores of solid business blocks into smoldering piles of brick.

Banks and commercial houses, supposed to be fireproof though not of modern build, burned quickly and the roar of the flames could be heard even on the hills, which were out of the danger zone. Here many thousands of people congregated and witnessed the awful scene. Great sheets of flame rose high in the heavens or rushed down some narrow street, joining midway between the [Pg 37]sidewalks and making a horizontal chimney of the former passage ways.

The dense smoke that arose from the entire business spread out like an immense funnel and could have been seen for miles out at sea. Occasionally, as some drug house or place stored with chemicals was reached, most fantastic effects were produced by the colored flames and smoke which rolled out against the darker background.

When the first shock occurred at 5:15 a. m. most of the population were in bed and many lodging houses collapsed with every occupant. There was no warning of the awful catastrophe. First came a slight shock, followed almost immediately by a second and then the great shock that sent buildings swaying and tumbling. Fire broke out immediately. Every able-bodied man who could be pressed into service was put to work rescuing the victims.

Panic seized most of the people and they rushed frantically about. Toward the ferry building there was a rush of those fleeing to cross the bay. Few carried any effects and some were hardly dressed. The streets were filled immediately with panic-stricken people and the frequently occurring shocks sent them into unreasoning panic. Fires lighted up the sky in every direction in the breaking dawn. In the business district devastation met the eye on every hand.

The area bounded by Washington, Mission and Montgomery streets and extending to the bay front was quickly devastated. That represented the heart of the handsome business section.

The greatest destruction on the first day occurred in that part of the city which was reclaimed from San Francisco Bay. Much of the devastated district was at one time low marshy ground entirely covered by water at high tide. As the city grew it became necessary to fill in many acres of this low ground in order to reach deep water. The Merchants’ Exchange building, a [Pg 38]fourteen-story steel structure, was situated on the edge of this reclaimed ground. It had just been completed and the executive offices of the Southern Pacific Company occupied the greater part of the building.

The damage by the earthquake to the residence portion of the city, the finest part of which was on Nob Hill and Pacific Heights, was slight but the fire completely destroyed that section on the following day.

To the westward, on Pacific Heights, were many fine, new residences, but little injury was done to any of them by the quake.

The Palace Hotel, a seven-story building about 300 feet square, was built thirty years ago by the late Senator Sharon, whose estate was in the courts for many years. At the time it was erected the Palace was considered the best equipped hotel in the west.

The offices of the three morning papers, the Chronicle, the Call and the Examiner, were located within 100 feet of each other. The Chronicle, situated at the corner of Market and Kearney streets, was a ten-story steel frame building and was one of the finest buildings of its character put up in San Francisco.

The Spreckels building, in which were located the business office of the Call, was sixteen stories high and very narrow. The editorial rooms, composing room and pressroom were in a small three-story building immediately in the rear of the Spreckels building.

Just across Third street was the home of the Examiner, seven stories high, with a frontage of 100 feet on Market street.

The postoffice was a fine, grey stone structure and had been completed less than two years. It covered half a block on Mission street between Sixth and Seventh streets. The ground on which the building stood was of a swampy character and some difficulty was experienced in obtaining a solid foundation.

[Pg 39]The City Hall, which was badly wrecked by the quake and afterwards swept by the fire, was a mile and a half from the water front. It was an imposing structure with a dome 150 feet high. The building covered about three acres and cost more than $7,000,000.

The Grand Opera House, where the Metropolitan Opera Company opened a two weeks’ engagement the previous Monday night, was one of the oldest theaters in San Francisco. It was located on Mission street between Third and Fourth streets and for a number of years was the leading playhouse of the city.

In 1885 when business began to move off of Mission street and to seek modern structures this playhouse was closed for some time and later devoted to vaudeville. Within the past four years, however, numerous fine buildings had been erected on Mission street and the Grand Opera house had been used by many of the leading independent theatrical companies.

All efforts to prevent the fire from reaching the Palace and Grand hotels were unsuccessful and both were completely destroyed together with all their contents.

All of San Francisco’s best playhouses, including the Majestic, Columbia, Orpheum and Grand Opera house were soon a mass of ruins. The earthquake demolished them for all practical purposes and the fire completed the work of demolition. The handsome Rialto and Casserly buildings were burned to the ground, as was everything in that district.

The scene at the Mechanics’ Pavilion during the early hours of the morning and up until noon, when all the injured and dead were removed because of the threatened destruction of the building by fire, was one of indescribable sadness. Sisters, brothers, wives and sweethearts searched eagerly for some missing dear one.

Thousands of persons hurriedly went through the building inspecting the cots on which the sufferers lay in the hope that they would locate some loved one that was missing.

[Pg 40]The dead were placed in one portion of the building and the remainder was devoted to hospital purposes. The fire forced the nurses and physicians to desert the building; the eager crowds followed them to the Presidio and the Children’s hospital, where they renewed their search for missing relatives.

The experience of the first day of the fire was a great testimonial to the modern steel building. A score of those structures were in course of erection and not one of them suffered. The completed modern buildings were also immune from harm by earthquake. The buildings that collapsed were all flimsy, wooden and old-fashioned brick structures.

On the evening of Wednesday, April 18, the first day of the fire, an area of thickly covered ground of eight square miles had been burned over and it was apparent that the entire city was doomed to destruction.

Nearly every famous landmark that had made San Francisco famous over the world had been laid in ruins or burned to the ground in the dire catastrophe. Never was the fate of a city more disastrous.

For three miles along the water front buildings had been swept clean and the blackened beams and great skeletons of factories and offices stood silhouetted against a background of flame that was slowly spreading over the entire city.

The whole commercial and office section of the city on the north side of Market street from the ferry building to Tenth street had been consumed in the hell of flame, while hardly a building was standing in the district south of Market street. At 2 o’clock in the afternoon, despite the heroic work of the firemen and the troops of dynamiters, who razed building after building and blew up property valued at millions, the flames spread across Market street to the north side and swept up Montgomery street, practically to Washington street. Along Montgomery street were some of the richest banks and commercial houses in San Francisco.

Copyright by R. L. Forrest 1906.

STREET TORN UP BY EARTHQUAKE.

A photograph of street in front of new Postoffice. Note how the car tracks are thrown up and twisted.

STOCKTON STREET FROM UNION SQUARE.

GRANT AVENUE FROM MARKET STREET.

MISSION STREET, SAN FRANCISCO.

Photographed from Fourth Street.

O’FARRELL STREET.

A new steel building which was being erected shown at the right.

LOOKING NORTH FROM SIXTH AND MARKET STREETS.

THE ORPHEUM THEATER ON O’FARRELL STREET.

[Pg 45]The famous Mills building and the new Merchants Exchange were still standing, but the Mutual Life Insurance building and scores of bank and office buildings were on fire, while blocks of other houses were in the path of the flames and nothing seemed to be at hand to stay their progress.

Nearly every big factory building had been wiped out of existence and a complete enumeration of them would look like a copy of the city directory.

Many of the finest buildings in the city had been leveled to dust by the terrific charges of dynamite in hopeless effort to stay the horror of fire. In this work many heroic soldiers, policemen and firemen were maimed or killed outright.

At 10 o’clock at night the fire was unabated and thousands of people were fleeing to the hills and clamoring for places on the ferry boats at the ferry landing.

From the Cliff House came word that the great pleasure resort and show place of the city, which stood upon a foundation of solid rock, had been swept into the sea. This report proved to be unfounded, but it was not until three days later that any one got close enough to the Cliff House to discover that it was still safe.

One of the big losses of the day was the destruction of St. Ignatius’ church and college at Van Ness avenue and Hayes street. This was the greatest Jesuitical institution in the west and built at a cost of $2,000,000.

By 7 o’clock at night the fire had swept from the south side of the town across Market street into the district called the Western addition and was burning houses at Golden Gate avenue and Octavia. This result was reached after almost the entire southern district from Ninth street to the eastern water front had been converted into a blackened waste. In this section were hundreds of factories, wholesale houses and many business firms, in addition to thousands of homes.

CHAPTER II.

SAN FRANCISCO A ROARING FURNACE.

Flames Spread in a Hundred Directions and the Fire Becomes the Greatest Conflagration of Modern Times—Entire Business Section and Fairest Part of Residence District Wiped Off the Map—Palaces of Millionaires Vanish in Flames or are Blown Up by Dynamite—The Worst Day of the Catastrophe.

MARIUS sitting among the ruins of Carthage saw not such a sight as presented itself to the afflicted people of San Francisco in the dim haze of the smoke pall at the end of the second day. Ruins stark naked, yawning at fearful angles and pinnacled into a thousand fearsome shapes, marked the site of what was three-fourths of the total area of the city.

Only the outer fringe of the city was left, and the flames which swept unimpeded in a hundred directions were swiftly obliterating what remained.

Nothing worthy of the name of building in the business district and not more than half of the residence district had escaped. Of its population of 400,000 nearly 300,000 were homeless.

Gutted throughout its entire magnificent financial quarters by the swift work of thirty hours and with a black ruin covering more than seven square miles out into her very heart, the city waited in a stupor the inevitable struggle with privation and hardship.

All the hospitals except the free city hospital had been destroyed, and the authorities were dragging the injured, sick and dying from place to place for safety.

All day the fire, sweeping in a dozen directions, irresistibly completed the desolation of the city. Nob Hill district, in which [Pg 47]were situated the home of Mrs. Stanford, the priceless Hopkins Art Institute, the Fairmount hotel, a marble palace that cost millions of dollars and homes of a hundred millionaires, was destroyed.

It was not without a struggle that Mayor Schmitz and his aides let this, the fairest section of the city, suffer obliteration. Before noon when the flames were marching swiftly on Nob Hill, but were still far off, dynamite was dragged up the steep debris laden streets. For a distance of a mile every residence on the east side of Van Ness avenue was swept away in a vain hope to stay the progress of the fire.

After sucking dry even the sewers the fire engines were either abandoned or moved to the outlying districts.

There was no help. Water was gone, powder was gone, hope even was a fiction. The fair city by the Golden Gate was doomed to be blotted from the sight of man.

The stricken people who wandered through the streets in pathetic helplessness and sat upon their scattered belongings in cooling ruins reached the stage of dumb, uncaring despair, the city dissolving before their eyes had no significance longer.

There was no business quarter; it was gone. There was no longer a hotel district, a theater route, a place where Night beckoned to Pleasure. Everything was gone.

But a portion of the residence domain of the city remained, and the jaws of the disaster were closing down on that with relentless determination.

All of the city south of Market street, even down to Islais creek and out as far as Valencia street, was a smouldering ruin. Into the western addition and the Pacific avenue heights three broad fingers of fire were feeling their way with a speed that foretold the destruction of all the palace sites of the city before the night would be over.

There was no longer a downtown district. A blot of black spread from East street to Octavia, bounded on the south and [Pg 48]north by Broadway and Washington streets and Islais creek respectively. Not a bank stood. There were no longer any exchanges, insurance offices, brokerages, real estate offices, all that once represented the financial heart of the city and its industrial strength.

Up Market street from the Ferry building to Valfira street nothing but the black fingers of jagged ruins pointed to the smoke blanket that pressed low overhead. What was once California, Sansome, and Montgomery streets was a labyrinth of grim blackened walls.

Chinatown was no more. Union square was a barren waste.

The Call building stood proudly erect, lifting its whited head above the ruin like some leprous thing and with all its windows, dead, staring eyes that looked upon nothing but a wilderness. The proud Flood building was a hollow shell.

The St. Francis Hotel, one time a place of luxury, was naught but a box of stone and steel.

Yet the flames leaped on exultantly. They leapt chasms like a waterfall taking a precipice. Now they are here, now there, always pressing on into the west and through to the end of the city.

It was supposed that the fire had eaten itself out in the wholesale district below Sansome street, and that the main body of the flames was confined to the district south of Market street, where the oil works, the furniture factories, and the vast lumber yards had given fodder into the mouth of the fire fiend.

Yet, suddenly, as if by perverse devilishness, a fierce wind from the west swept over the crest of Nob Hill and was answered by leaping tongues of flames from out of the heart of the ruins.

By 8:30 o’clock Montgomery street had been spanned and the great Merchants’ Exchange building on California street flamed out like the beacon torch of a falling star. From the dark fringe of humanity, watching on the crest of the California street hill, there sprang the noise of a sudden catching of the breath—not a [Pg 49]sigh, not a groan—just a sharp gasp, betraying a stress of despair near to the insanity point.

Nine o’clock and the great Crocker building shot sparks and added tongues of fire to the high heavens. Immediately the fire jumped to Kearney street, licking at the fat provender that shaped itself for consuming.

Then began the mournful procession of Japanese and poor whites occupying the rookeries about Dupont street and along Pine. Tugging at heavy ropes, they rasped trunks up the steep pavements of California and Pine streets to places of temporary safety.

It was a motley crew. Women laden with bundles and dragging reluctant children by the hands panted up the steep slope with terror stamped on their faces.

Men with household furniture heaped camelwise on their shoulders trudged stoically over the rough cobbles, with the flame of the fire bronzing their faces into the outlines of a gargoyle. One patriotic son of Nippon labored painfully up Dupont street with the crayon portrait of the emperor of Japan on his back.

While this zone of fire was swiftly gnawing its way through Kearney street and up the hill, another and even more terrible segment of the conflagration was being stubbornly fought at the corner of Golden Gate avenue and Polk street. There exhausted firemen directed the feeble streams from two hoses upon a solid block of streaming flame.

The engines pumped the supply from the sewers. Notwithstanding this desperate stand, the flames progressed until they had reached Octavia street.

Like a sickle set to a field of grain the fiery crescent spread around the southerly end of the west addition up to Oak and Fell streets, along Octavia. There one puny engine puffed a single stream of water upon the burning mass, but its efforts were like the stabbing of a pigmy at a giant.

[Pg 50]All the district bounded by Octavia, Golden Gate avenue, and Market street was a blackened ruin. One picked his way through the fallen walls on Van Ness avenue as he would cross an Arizona mesa. It was an absolute ruin, gaunt and flame lighted.

From the midst rose the great square wall of St. Ignatius college, standing like another ruined Acropolis in dead Athens.

Behind the gaunt specter of what had once been the city hall a blizzard of flame swept back into the gore between Turk and Market streets. Peeled of its heavy stone facing like a young leek that is stripped of its wrappings, the dome of the city hall rose spectral against the nebulous background of sparks.

From its summit looked down the goddess of justice, who had kept her pedestal even while the ones of masonry below her feet had been toppled to the earth in huge blocks the size of a freight car.

Through the gaunt iron ribs and the dome the red glare suffusing the whole northern sky glinted like the color of blood in a hand held to the sun.

At midnight the Hibernian bank was doomed, for from the frame buildings west of it there was being swept a veritable maelstrom of sheet flame that leaped toward it in giant strides. Not a fireman was in sight.

Across the street amid the smoke stood the new postoffice, one of the few buildings saved. Turk street was the northern boundary of this V shaped zone of the flames, but at 2 o’clock this street also was crossed and the triumphant march onward continued.

At midnight another fire, which had started in front of Fisher’s Music Hall, on O’Farrell street, had gouged its terrible way through to Market street, carrying away what the morning’s blaze across the street had left miraculously undestroyed.

Into Eddy and Turk streets the flames plunged, and soon the magnificent Flood building was doomed.

The firemen made an ineffectual attempt to check the ravages [Pg 51]of the advancing phalanx of flames, but their efforts were absolutely without avail. First from across the street shot tongues of flames which cracked the glass in one of the Flood building’s upper story windows. Then a shower of sparks was sent driving at a lace curtain which fluttered out in the draft. The flimsy whipping rag caught, a tongue of flame crept up its length and into the window casement.

“My God, let me get out of this,” said a man below who had watched the massive shape of the huge pile arise defiant before the flames. “I can’t stand to see that go, too.”

Shortly after midnight the streets about Union Square were barred by the red stripes of the fire. First Cordes Furniture Company’s store went, then Brennor’s. Next a tongue of flames crept stealthily into the rear of the City of Paris store, on the corner of Geary and Stockton streets.

Eager spectators watched for the first red streamers to appear from the windows of the great dry goods stores. Smoke eddied from under window sills and through cracks made by the earthquake in the cornices. Then the cloud grew denser. A puff of hot wind came from the west, and as if from the signal there streamed flamboyantly from every window in the top floor of the structure billowing banners, as a poppy colored silk that jumped skyward in curling, snapping breadths, a fearful heraldry of the pomp of destruction.

From the copper minarets on the Hebrew synagogue behind Union square tiny green, coppery flames next began to shoot forth. They grew quickly larger, and as the heat increased in intensity there shone from the two great bulbs of metal sheathing an iridescence that blinded like a sight into a blast furnace.

With a roar the minarets exploded almost simultaneously, and the sparks shot up to mingle with the dulled stars overhead. The Union League and Pacific Union clubs next shone red with the fire that was glutting them.

On three sides ringed with sheets of flame rose the Dewey [Pg 52]memorial in the midst of Union square. Victory tiptoeing on the apex of the column glowed red with the flames. It was as if the goddess of battle had suddenly become apostate and a fiend linked in sympathy with the devils of the blaze.

On the first day of the catastrophe the St. Francis escaped. On the second it fell. In the space of two hours the flames had blotted it out, and by night only the charred skeleton remained.

As a prelude to the destruction of the St. Francis the fire swept the homes of the Bohemian, Pacific, Union, and Family clubs, the best in San Francisco.

With them were obliterated the huge retail stores along Post street; St. Luke’s Church, the biggest Episcopal church on the Pacific coast, and the priceless Hopkins Art Institute.

From Union square to Chinatown it is only a pistol shot. By noon all Chinatown was a blazing furnace, the rickety wooden hives, where the largest Chinese colony in this country lived, was perfect fuel for the fire.

Then Nob Hill, the charmed circle of the city, the residential district of its millionaires and of those whose names have made it famous, went with the rest of the city into oblivion. The Fairmount Hotel, marble palace built by Mrs. Oelrichs, crowned this district.

Grouped around it were the residences of Mrs. Stanford, and a score of millionaires’ homes on Van Ness avenue. One by one they were buried in the onrushing flames, and when the fire was passed they were gone.

Here the most desperate effort of the fight to save the city was made. Nothing was spared. There was no discrimination, no sentiment. Rich men aided willingly in the destruction of their own homes that some of the city might be saved.

Copyright 1906, by American-Journal-Examiner. All rights reserved. Any infractions

of this copyright will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

of this copyright will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

VIEW FROM VALLEY STREET.

This is a view from Valley Street looking down Kearney toward Market.

Copyright 1906, by American-Journal-Examiner. All rights reserved. Any infractions

of this copyright will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

of this copyright will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

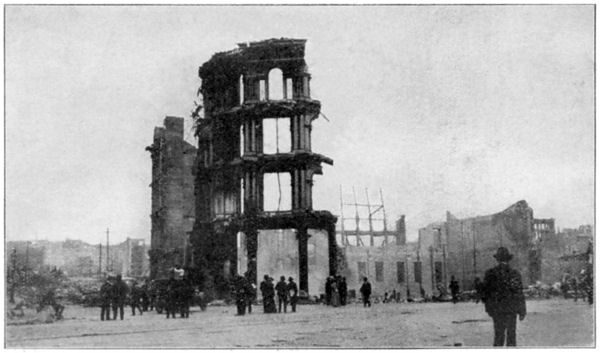

DESTROYED WHOLESALE HOUSES.

This photograph shows the wreck and ruin wrought by the earthquake and fire in the wholesale district.

But the sacrifice and the labor went for nothing. No human power could stay the flames. As darkness was falling the fire was eating its way through the heart of this residential district. [Pg 55]The mayor was forced to announce that the last hope had been dashed.

All the district bounded by Union, Van Ness, Golden Gate, to Octavia, Hayes, and Fillmore to Market was doomed. The fire fighters, troops, citizens, and city officials left the scene, powerless to do more.

On the morning of the second day when the fire reached the municipal building on Portsmouth square, the nurses, helped by soldiers, got out fifty bodies in the temporary morgue and a number of patients in the receiving hospital. Just after they reached the street a building was blown up and the flying bricks and splinters hurt a number of the soldiers, who had to be taken to the out of doors Presidio Hospital with the patients.

Mechanics’ pavilion, which, after housing prize fights, conventions, and great balls, found its last use as an emergency hospital. When it was seen that it could not last every vehicle in sight was impressed by the troops, and the wounded, some of them frightfully mangled, were taken to the Presidio, where they were out of danger and found comfort in tents.

The physicians worked without sleep and almost without food. There was food, however, for the injured; the soldiers saw to that. Even the soldiers flagged, and kept guard in relays, while the relieved men slept on the ground where they dropped.

The troops shut down with iron hands on the city, for where one man was homeless the first night five were homeless the second night. With the fire running all along the water front, few managed to make their way over to Oakland. The people for the most part were prisoners on the peninsula.

The soldiers enforced the rule against moving about except to escape the flames, and absolutely no one could enter the city who once had left.

The seat of city government and of military authority shifted with every shift of the flames. Mayor Schmitz and General Funston stuck close together and kept in touch with the firemen [Pg 56]and police, the volunteer aids, and the committee of safety through couriers.

There were loud reverberations along the fire line at night. Supplies of gun cotton and cordite from the Presidio were commandeered and the troops and the few remaining firemen made another futile effort to check the fiery advance.

Along the wharves the fire tugs saved most of the docks. But the Pacific mail dock had been reached and was out of control; and finally China basin, which was filled in for a freight yard at the expense of millions of dollars, had sunk into the bay and the water was over the tracks. This was one of the greatest single losses in the whole disaster.

Without sleep and without food, crowds watched all night Wednesday and all day Thursday from the hills, looking off toward that veil of fire and smoke that hid the city which had become a hell.

Back of that sheet of fire, and retreating backward every hour, were most of the people of the city, forced toward the Pacific by the advance of the flames. The open space of the Presidio and Golden Gate park was their only haven and so the night of the second day found them.

CHAPTER III.

THIRD DAY ADDS TO HORROR.

Fire Spreads North and South Attended by Many Spectacular Features—Heroic Work of Soldiers Under General Funston—Explosions of Gas Add to General Terror.

THE third day of the fire was attended by many spectacular features, many scenes of disaster and many acts of daring heroism.

When night came the fire was raging over fifty acres of the water front lying between Bay street and the end of Meiggs and Fisherman’s wharf. To the eastward it extended down to the sea wall, but had not reached the piers, which lay a quarter of a mile toward the east.

The cannery and warehouses of the Central California Canneries Company, together with 20,000 cases of canned fruit, was totally destroyed, as also was the Simpson and other lumber companies’ yards.

The flames reached the tanks of the San Francisco Gas Company, which had previously been pumped out, and had burned the ends of the grain sheds, five in number, which extended further out toward the point.

Flame and smoke hid from view the vessels that lay off shore vainly attempting to check the fire. No water was available except from the waterside and it was not until almost dark that the department was able to turn its attention to this point.

At dusk the fire had been checked at Van Ness avenue and Filbert street. The buildings on a high slope between Van Ness and Polk, Union and Filbert streets were blazing fiercely, fanned by a high wind, but the blocks were so sparsely settled [Pg 58]that the fire had but a slender chance of crossing Van Ness at that point.

Mayor Schmitz, who directed operations at that point, conferred with the military authorities and decided that it was not necessary to dynamite the buildings on the west side of Van Ness. As much of the fire department as could be collected was assembled to make a stand at that point.

To add to the horrors of the general situation and the general alarm of many people who ascribed the cause of the subterranean trouble to another convulsion of nature, explosions of sewer gas have ribboned and ribbed many streets. A Vesuvius in miniature was created by such an upheaval at Bryant and Eighth streets. Cobblestones were hurled twenty feet upward and dirt vomited out of the ground. This situation added to the calamity, as it was feared the sewer gas would breed disease.

Thousands were roaming the streets famishing for food and water and while supplies were coming in by the train loads the system of distribution was not in complete working order.

Many thousands had not tasted food or water for two and three days. They were on the verge of starvation.

The flames were checked north of Telegraph hill, the western boundary being along Franklin street and California street southeast to Market street. The firemen checked the advance of flames by dynamiting two large residences and then backfiring. Many times before had the firemen made such an effort, but always previously had they met defeat.

But success at that hour meant little for San Francisco.

The flames still burned fitfully about the city, but the spread of fire had been checked.

A three-story lodging house at Fifth and Minna streets collapsed and over seventy-five dead bodies were taken out. There were at least fifty other dead bodies exposed. This building [Pg 59]was one of the first to take fire on Fifth street. At least 100 people were lost in the Cosmopolitan on Fourth street.

The only building standing between Mission, Howard, East and Stewart streets was the San Pablo hotel. The shot tower at First and Howard streets was gone. This landmark was built forty years ago. The Risdon Iron works were partially destroyed. The Great Western Smelting and Refining works escaped damages, also the Mutual Electric Light works, with slight damage to the American Rubber Company, Vietagas Engine Company, Folger Brothers’ coffee and spice house was also uninjured and the firm gave away large quantities of bread and milk.

Over 150 people were lost in the Brunswick hotel, Seventh and Mission streets.

The soldiers who rendered such heroic aid took the cue from General Funston. He had not slept. He was the real ruler of San Francisco. All the military tents available were set up in the Presidio and the troops were turned out of the barracks to bivouac on the ground.

In the shelter tents they placed first the sick, second the more delicate of the women, and third, the nursing mothers, and in the afternoon he ordered all the dead buried at once in a temporary cemetery in the Presidio grounds. The recovered bodies were carted about the city ahead of the flames.

Many lay in the city morgue until the fire reached that; then it was Portsmouth square until it grew too hot; afterwards they were taken to the Presidio. There was another stream of bodies which had lain in Mechanics’ pavilion at first, and had then been laid out in Columbia square, in the heart of a district devastated first by the earthquake and then by fire.

The condition of the bodies was becoming a great danger. Yet the troops had no men to spare to dig graves, and the young and able bodied men were mainly fighting on the fire line or utterly exhausted.

[Pg 60]It was Funston who ordered that the old men and the weaklings should take this work in hand. They did it willingly enough, but had they refused the troops on guard would have forced them. It was ruled that every man physically capable of handling a spade or a pick should dig for an hour. When the first shallow graves were ready the men, under the direction of the troops, lowered the bodies several in a grave, and a strange burial began.

The women gathered about crying; many of them knelt while a Catholic priest read the burial service and pronounced absolution. All the afternoon this went on.

Representatives of the city authorities took the names of as many of the dead as could be identified and the descriptions of the others. Many, of course, will never be identified.

So confident were the authorities that they had the situation in control at the end of the third day that Mayor Schmitz issued the following proclamation:

“To the Citizens of San Francisco: The fire is now under control and all danger is passed. The only fear is that other fires may start should the people build fires in their stoves and I therefore warn all citizens not to build fires in their homes until the chimneys have been inspected and repaired properly. All citizens are urged to discountenance the building of fires. I congratulate the citizens of San Francisco upon the fortitude they have displayed and I urge upon them the necessity of aiding the authorities in the work of relieving the destitute and suffering. For the relief of those persons who are encamped in the various sections of the city everything possible is being done. In Golden Gate park, where there are approximately 200,000 homeless persons, relief stations have been established. The Spring Valley Water Company has informed me that the Mission district will be supplied with water this afternoon, between 10,000 and 12,000 gallons daily being available. Lake Merced will be taken by the federal troops and that supply protected.

“Eugene E. Schmitz, Mayor.”

[Pg 61]Although the third day of San Francisco’s desolation dawned with hope, it ended in despair.

In the early hours of the day the flames, which had raged for thirty-six hours, seemed to be checked.

Then late in the afternoon a fierce gale of wind from the northwest set in and by 7 o’clock the conflagration, with its energy restored, was sweeping over fifty acres of the water front.

The darkness and the wind, which at times amounted to a gale, added fresh terrors to the situation. The authorities considered conditions so grave that it was decided to swear in immediately 1,000 special policemen armed with rifles furnished by the federal government.

In addition to this force, companies of the national guard arrived from many interior points.