- Key Identifiers for Mobile Devices

- Who can access what on a mobile device?

- Device Tracking by Third Parties Using Identifiers

- Data Gathering and Surveillance by State Actors

THE NSA AND GCHQ CAMPAIGN AGAINST GERMAN SATELLITE COMPANIES

Andy Müller-Maguhn, Laura Poitras, Marcel Rosenbach, Michael Sontheimer, Christian Grothoff

September 14 2014, 12:00 p.m.

“Fuck!” That is the word that comes to the mind of Christian Steffen, the CEO of German satellite communications company Stellar PCS. He is looking at classified documents laying out the scope of something called Treasure Map, a top secret NSA program. Steffen’s firm provides internet access to remote portions of the globe via satellite, and what he is looking at tells him that the company, and some of its customers, have been penetrated by the U.S. National Security Agency and British spy agency GCHQ.

Stellar’s visibly shaken chief engineer, reviewing the same documents, shares his boss’ reaction. “The intelligence services could use this data to shut down the internet in entire African countries that are provided access via our satellite connections,” he says.

Treasure Map is a vast NSA campaign to map the global internet. The program doesn’t just seek to chart data flows in large traffic channels, such as telecommunications cables.

Rather, it seeks to identify and locate every single device that is connected to the internet somewhere in the world—every smartphone, tablet, and computer—”anywhere, all the time,” according to NSA documents.

The breathtaking mission is described in a document from the archive of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden provided to The Intercept and Der Spiegel. Treasure Map’s goal is to create an “interactive map of the global internet” in “almost real time.” Employees of the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance—England, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—can install and use the program on their own computers. It evokes a kind of Google Earth for global data traffic, a bird’s eye view of the planet’s digital arteries.

(The short film above, Chokepoint, by filmmaker Katy Scoggin and Intercept co-founder Laura Poitras, documents the reactions of Stellar engineers when confronted with evidence that their company—and they themselves—had been surveilled by GCHQ.)

The New York Times reported on the existence of Treasure Map last November. Though the NSA documents indicate that it can be used to monitor “adversaries,” and for “computer attack/exploit planning”—offering a kind of battlefield map for cyber warfare—they also clearly show that Treasure Map monitors traffic and devices inside the United States. Unnamed intelligence officials told the Times that the program didn’t have the capacity to monitor all internet-connected devices, and was focused on foreign networks, as well as the U.S. Defense Department’s own computer systems.

September 14 2014, 12:00 p.m.

“Fuck!” That is the word that comes to the mind of Christian Steffen, the CEO of German satellite communications company Stellar PCS. He is looking at classified documents laying out the scope of something called Treasure Map, a top secret NSA program. Steffen’s firm provides internet access to remote portions of the globe via satellite, and what he is looking at tells him that the company, and some of its customers, have been penetrated by the U.S. National Security Agency and British spy agency GCHQ.

Stellar’s visibly shaken chief engineer, reviewing the same documents, shares his boss’ reaction. “The intelligence services could use this data to shut down the internet in entire African countries that are provided access via our satellite connections,” he says.

Treasure Map is a vast NSA campaign to map the global internet. The program doesn’t just seek to chart data flows in large traffic channels, such as telecommunications cables.

Rather, it seeks to identify and locate every single device that is connected to the internet somewhere in the world—every smartphone, tablet, and computer—”anywhere, all the time,” according to NSA documents.

Its internal logo depicts a skull superimposed onto a compass, the eyeholes glowing demonic red.

The breathtaking mission is described in a document from the archive of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden provided to The Intercept and Der Spiegel. Treasure Map’s goal is to create an “interactive map of the global internet” in “almost real time.” Employees of the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance—England, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—can install and use the program on their own computers. It evokes a kind of Google Earth for global data traffic, a bird’s eye view of the planet’s digital arteries.

(The short film above, Chokepoint, by filmmaker Katy Scoggin and Intercept co-founder Laura Poitras, documents the reactions of Stellar engineers when confronted with evidence that their company—and they themselves—had been surveilled by GCHQ.)

The New York Times reported on the existence of Treasure Map last November. Though the NSA documents indicate that it can be used to monitor “adversaries,” and for “computer attack/exploit planning”—offering a kind of battlefield map for cyber warfare—they also clearly show that Treasure Map monitors traffic and devices inside the United States. Unnamed intelligence officials told the Times that the program didn’t have the capacity to monitor all internet-connected devices, and was focused on foreign networks, as well as the U.S. Defense Department’s own computer systems.

A slide from an NSA presentation explaining Treasure Map

The Treasure Map graphics contained in the Snowden archive don’t just provide detailed views of global networks—they also note which carriers and internal service provider networks Five Eyes agencies claim to have already penetrated. In graphics generated by the program, some of the “autonomous systems”—basically, networks of routers all controlled by one company, referred to by the shorthand “AS”—under Treasure Map’s watchful eye are marked in red. An NSA legend explains what that means: “Within these AS, there are access points for technical monitoring.” In other words, they are under observation.

In one GCHQ document, an AS belonging to Stellar PCS is marked in red, as are networks that belong to two other German firms, Deutsche Telekom AG and Netcologne, which operates a fiber-optic network and provides telephone and internet services to 400,000 customers.

Deutsche Telekom, of which the German government owns more than 30 percent, is one of the dozen or so international telecommunications companies that operate global networks—so-called Tier 1 providers. In Germany alone, Deutsche Telekom claims to provide mobile phone services, internet, and land lines to 60 million customers.

It’s not clear from the documents how or where the NSA gained access to the networks. Deutsche Telekom’s autonomous system, marked in red, includes several thousand routers worldwide. It has operations in the U.S. and England, and is part of a consortium that operates the TAT14 transatlantic cable system, which stretches from England to the east coast of the U.S. “The accessing of our network by foreign intelligence agencies,” said a Telekom spokesperson, “would be completely unacceptable.”

The fact that Netcologne is a regional provider, with no international operations, would seem to indicate that the NSA or one of its partners accessed the network from within Germany. If so, that would be a violation of German law and potentially another NSA-related case for German prosecutors, who have been investigating the monitoring of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s mobile phone.

Reporters for Der Spiegel, working in collaboration with The Intercept, contacted both companies several weeks ago in order to give them an opportunity to look into the alleged security breaches themselves. The security departments of both firms say they launched intensive investigations, but failed to find any suspicious equipment or data streams leaving the network. The NSA declined to comment for this story, and GCHQ offered no response beyond its boilerplate claim that all its activities are lawful.

Deutsche Telekom and Netcologne are not the first German companies to be pinpointed by Snowden documents as having been successfully hacked by intelligence agencies. In March, Der Spiegel reported on a large-scale attack by GCHQ on German satellite operators Stellar, Cetel, and IABG, all of which offer satellite internet connections to remote regions of the world. All three companies operate their own autonomous systems. And all three are marked red in Treasure Map graphics.

Der Spiegel also contacted 11 of the international providers listed in the Treasure Map document. Four answered, all saying they examined their systems and were unable to find any irregularities. “We would be extremely concerned if a foreign government were to seek unauthorized access to our global networks and infrastructure,” said a spokesperson for the Australian telecommunications company Telstra.

The case of Stellar illustrates the lengths to which GCHG and NSA have gone in making their secret map of the internet, and its users.

One document, from GCHQ’s Network Analysis Center, lays out what appears to be an attack on Stellar. The document lists “central employees” at the company, and states that they should be identified and “tasked.” To “task” somebody, in signals intelligence jargon, is to engage in electronic surveillance. In addition to Stellar CEO Christian Steffen, nine other employees are named in the document.

The attack on Stellar has notable similarities with the GCHQ surveillance operation targeting the Belgian provider Belgacom, which Der Spiegel reported last year. There too, the GCHQ Network Analysis department penetrated deeply into the Belgacom network and that of its subsidiary BICS by hacking employee computers. They then prepared routers for cyber attacks.

Der Spiegel reporters visited Stellar at its headquarters in Hürth, near Cologne, and presented the documents to Steffen and three of his “tasked” employees. They were able to recognize, among other things, a listing for their central server as well as the company’s mail server, which the GCHQ attackers appear to have hacked.

The document also lays out the intelligence gathered from the spying efforts, including an internal table that shows which Stellar customers are being served by which specific satellite transponders. “Those are business secrets and sensitive information,” said Stellar’s visibly shocked IT chief, Ali Fares, who is himself cited in the document as an employee to be “tasked.”

The Stellar officials expressed alarm when they saw the password for the central server of an important customer. The significance of the theft is immense, Fares said. “This is really disturbing.”

Steffen, after spitting out his four-letter assessment, said he considers the documents to constitute proof that his company’s systems were breached illegally. “The hacked server has always stood behind our company’s own firewall,” he said. “The only way of accessing it is if you first successfully break into our network.” The company in question is no longer a customer with Stellar.

When asked if there are any reasons that would prompt England, a European Union partner country, to take such an aggressive approach to Stellar, Steffen shrugged his shoulders, perplexed. “Our customer traffic doesn’t run across conventional fiber optic lines,” he said. “In the eyes of intelligence services, we are apparently seen as difficult to access.” Still, he said, “that doesn’t give anyone the right to break in.”

“A cyber attack of this nature is a clear criminal offense under German law,” he continued. “I want to know why we were a target and exactly how the attack against us was conducted—if for no other reason than to be able to protect myself and my customers from this happening again.” Steffen wrote a letter to the British ambassador in Berlin asking for an explanation, but says he never received an answer.

Meanwhile, Deutsche Telekom’s security division has conducted a forensic review of important routers in Germany, but has yet to detect anything. Volker Tschersich, who heads the security division, says it’s possible the red dots in Treasure Map can be explained as access to the TAT14 cable, in which Telekom occupies a frequency band in England and the U.S. At the end of last week, the company informed Germany’s Federal Office for Information Security of the findings of Der Speigel‘s reporting.

The classified documents also indicate that other data from Germany contributes to keeping the global treasure map up to date. Of the 13 servers the NSA operates around the world in order to track current data flows on the open Internet, one is located somewhere in Germany.

Like the other servers, this one, which feeds data into the secret NSA network, is “covered” in an inconspicuous “data center.”

CONTACT THE AUTHOR:

___

IMEI: International Mobile Equipment Identity— Edward Snowden (@Snowden) October 22, 2019

IMSI: International Mobile Subscriber Identity

Just two of the digital identity cards inside your phone that make it possible for a global network to monitor your daily movements and activities. https://t.co/rYDF9N8gDH

The Many Identifiers in Our PocketsA primer on mobile privacy and security

Version 1.0 May 13, 2015

The phones and tablets that we carry constantly transmit a steady stream of information to third parties. Our searches, shares, and messages represent only a fraction of the sensitive, private, and identifiable data that our devices generate. The data includes many ‘identifiers,’ ranging from a serial-like IMEI number that is unique to each handset to unique operating system identifiers and even location information.

Some of these identifiers are personally identifiable and ‘baked in’ to the devices we carry around with us, while others are created as we use apps or browse the Internet. Moreover, many of these identifiers are transmitted and collected without notification to users, ending up with third parties, including app developers and advertising partners.

Some of these identifiers are personally identifiable and ‘baked in’ to the devices we carry around with us, while others are created as we use apps or browse the Internet. Moreover, many of these identifiers are transmitted and collected without notification to users, ending up with third parties, including app developers and advertising partners.

The constant transmission of identifier data is important to delivering seamless and tailored services and content to users. However, the uniquely revealing nature of identifiers, combined with the inconsistencies in how they are collected, transmitted, and secured, raise serious security and privacy concerns.

This document:

- Describes key identifiers for mobile devices.

- Highlights some identifiers that are accessible, and often collected, by various parties.

- Highlights the risks associated with the widespread transmission and use of these identifiers.

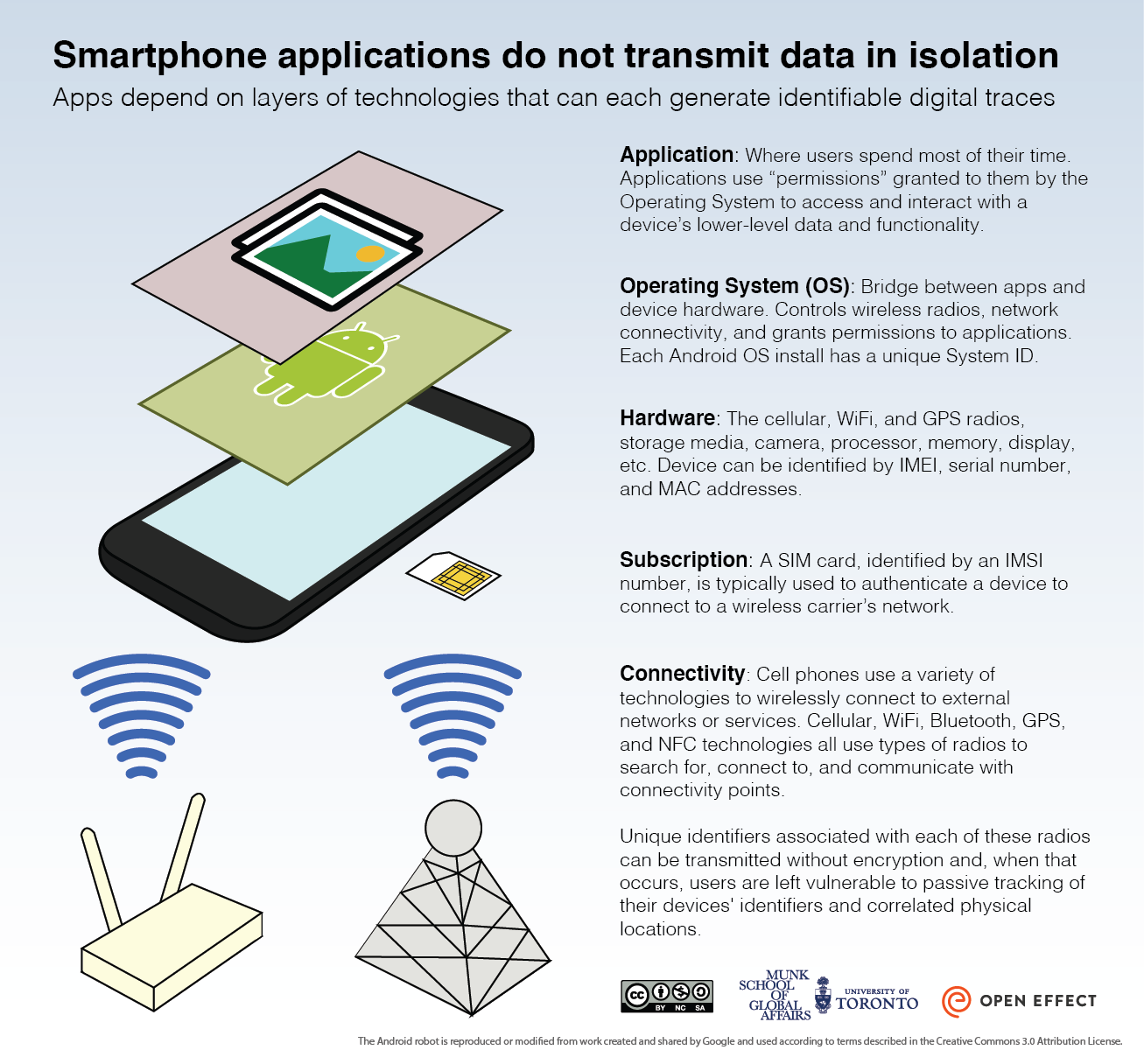

Key Identifiers for Mobile Devices

Mobile devices are assigned many identifiers that are used by hardware manufacturers, telecommunications service providers, operating system manufacturers, advertisers, and application developers. The identifiers are used to register devices to mobile networks, to ensure that operating systems operate smoothly, and that applications work correctly. They can also be used to facilitate user tracking, and for targeting advertising.

In what follows we discuss some of the different kinds of identifiers that are present at several levels (see Figure 1):

- Physical device (e.g., cell phones)

- Communications network (e.g., AT&T)

- Operating System (e.g., Android or iOS)

- Application layer (e.g., Angry Birds)

Physical Device

| Acronym | What it does |

|---|---|

| MAC Address | Media Access Control address uniquely identifies wireless transmitters like Bluetooth and Wi-Fi chips in the device |

| IMEI1 | The International Mobile Equipment Identifier is a string of numbers that is unique for every device |

Table 1: Selected Physical Device Identifiers

There are a set of ‘hard baked’ identifiers associated with different components of mobile devices. The various radios that are integrated with the device, such as those associated with cellular, wireless, bluetooth, and near field communications, are all assigned unique Media Access Control (MAC) addresses. The MAC address is assigned to a radio, although it can sometimes be rewritten using software programs. The MAC address of the device’s Wi-Fi chip is typically broadcast when Wi-Fi is enabled and the device is searching for access points. The International Mobile Equipment Identifier (IMEI) is tied to physical devices and remains the same throughout the life of the device. The IMEI denotes the standards board responsible for assigning the identifier, the time that it was manufactured, the serial number issued to the model of the device, and the version of the software installed on the phone.

Communications Network

| Acronym | What it does |

|---|---|

| MIN / MSIN | The Mobile Identification Number or Mobile Subscription Identification Number uniquely identifies a mobile device to a carrier. The number is included in the IMSI as an important identifier. |

| SIM | The Subscriber Identification Module identifies and authenticates the phone and user to the network, has a unique serial number, and holds substantial information about the user. |

| IMSI | The International Mobile Subscriber Identification number uniquely identifies the user. |

| Device IP Address | With mobile data, devices are typically assigned a network IP address. |

| MSISDN | The Mobile Subscriber Integrated Services Digital Network number includes the caller’s phone number, and uniquely identifies a particular subscriber’s SIM card. |

Table 2: Selected Communications Network Identifiers

The operators of communications networks, like mobile carriers (e.g., AT&T), or the operators of a Wi-Fi connection (e.g., coffee shops), can read a range of identifiers from devices. In the case of carriers, they also assign their own identifiers.

Mobile Carriers

Mobile service operators typically assign identifiers that register subscribers to cellular networks. The Mobile Identification Number (MIN) or Mobile Subscription Identification Number (MSIN) are used to uniquely identify a subscriber. A Subscriber Identification Module (SIM), commonly referred to as a “SIM Card,” includes information about which carrier is associated with the module, its time of manufacture and other carrier-specific information, as well as a serial number uniquely linked with the SIM itself. The SIM is identified to the network with an International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number2, which in turn identifies the mobile country code, network code, and mobile subscription identification number. In the case of cellular data, a network IP addresses is also assigned to the device.

Using identifiers like the IMSI, cellular operators typically collect geolocation records of mobile devices movements based on proximity to cellular towers. They also collect billing and usage information (e.g., websites visited, numbers dialled out, numbers dialled in, messages sent and received, etc.).

Using identifiers like the IMSI, cellular operators typically collect geolocation records of mobile devices movements based on proximity to cellular towers. They also collect billing and usage information (e.g., websites visited, numbers dialled out, numbers dialled in, messages sent and received, etc.).

Wi-Fi Operators

In comparison to cellular providers, Wi-Fi operators tend to issue or require fewer identifiers. Wi-Fi operators will most commonly assign IP address information, though they may also require authentication credentials in order to log into the Wi-Fi hotspot. However, it is difficult to generalize about the practices of Wi-Fi operators, as they have widely varying policies about collecting and retaining data transmitted by users’ devices.

Importantly, communications network providers (both mobile and Wi-Fi) are often able to read, retain/log, or make decisions based on the identifiers and data that are transmitted on their networks. For example, a communications provider can watch for the identifiers linked to a physical device as well as the identifiers associated with operating systems and applications. After reading the identifiers, they can log the presence of the identifiers for billing or marketing purposes, as well as make decisions whether or not to provide the device with service.

Importantly, communications network providers (both mobile and Wi-Fi) are often able to read, retain/log, or make decisions based on the identifiers and data that are transmitted on their networks. For example, a communications provider can watch for the identifiers linked to a physical device as well as the identifiers associated with operating systems and applications. After reading the identifiers, they can log the presence of the identifiers for billing or marketing purposes, as well as make decisions whether or not to provide the device with service.

Operating System

| Acronym | What it does |

|---|---|

| IFA | Apple’s Identifier For Advertisers lets app developers track users and replaces the UDID (Unique Device Identifier)3 |

| Android Identifier | A unique number generated when the operating system is first run that can be used to track users. |

| Google Wallet & Apple Pay | Payment services linked to both devices and accounts. |

Table 3: Selected Operating System Identifiers

Mobile operating system developers, such as Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Blackberry, can also include identifiers that assist users in operating their devices and provide resources to developers responsible for creating applications for the respective manufacturers’ operating systems.

Android devices, for example, have the Android Identifier that is generated the first time a newly installed Android OS is booted.4 Previously, Apple devices both used and shared a UDID (Unique Device Identifier) with applications. After privacy and security concerns were raised by researchers and the press, Apple introduced a separate number in more recent versions of iOS that is called the Identifier for Advertisers (IFA). The IFA (which can be disabled by a device owner) lets advertisers track user behavior across activities.

Sometimes operating systems providers will prompt users to generate new identifiers or credentials, such as a new Google account, Microsoft Live account, or AppleID. A growing number of companies, including Google (Google Wallet) and Apple (Apple Pay) are also integrating mobile payment services with near field communication options built into devices. In addition, mobile carriers sometimes integrate these payment options with mobile app stores, like Google Play or the App Store. Users may also be asked to provide ‘crash’ information to the operating system manufacturer, and such information may contain details about the user’s device and their usage of it.

Application Layer

Finally, application makers develop identifiers for authentication and advertising purposes. They may require users to create or sign in using authentication credentials or, when paying for items, either pay through operating system-based payment systems or through their own independent payment gateways. Applications may also ‘leak’ identifying information about the application itself, such as declaring their name, version information, or communications protocol in the user-agent identification string.5

Applications may also request access to sensor (e.g. accelerometer) or communications data, such as GPS, Wi-Fi, or SMS information. Applications can also request user data, such as contacts and files. Still other applications request a wide range of information from user devices, not all of it clearly aligned with the advertised functionality of the app. Even if the application itself is only using the “necessary” permissions for functionality, advertising networks included in the application may be “piggy backing” on the permissions requested by the app in order to access identifying data.

Access to these pieces of data is typically referred to as ‘permissions’; only once a user or device owner has permitted the application to read this information does it gain access to the requested sensor, user, or communications data.

Surveys of mobile device applications have shown that applications request access to more information than they require to perform their stated functions (e.g., a calculator application requesting access to geolocation, SMS, and call log information). Such overbroad requests for data on mobile devices create privacy problems, including: the user may not know that personal data is shared; the app developer may share data with third parties; the data may not be transmitted securely; and, the data may not be stored securely.

Who can access what on a mobile device?

The range of identifiers discussed previously are not accessible to all of the different parties involved in facilitating and enabling mobile device-based communications. Table 4 provides a general summary of the kinds of data available to each party. However, given the complexity of the ecosystem it is difficult to generalize, and there is likely to be variation in specific cases.

| Identifier | Cellular Provider | Wi-Fi Provider | OS Vendor | Application Developer6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAC Address | X | X | X | X |

| IMEI | X | X | X | |

| SIM | X | X | X | |

| IMSI | X | X | X | |

| IP Address | X | X | X | X |

| Phone Number | X | X | X | |

| ESN | X | X | X | |

| GPS | *7 | X | X | |

| Wi-Fi | X | X | X | |

| Bluetooth ID | X | X | ||

| Login/Payment Credentials | *8 | X | X | X |

Table 4: Mobile Identifiers and who has access to them

Cellular Provider

Cellular providers typically possess a wide range of information about you; in addition to the identifiers, denoted in Table 4, they may have payment information for post-billing purposes, government identification information when that kind of information must be provided to receive a SIM card, credit information, and more. These additional kinds of information may be needed to satisfy business or regulatory requirements.

Wi-Fi Provider

The provider of the Wi-Fi network to which a device is connected can capture and read unencrypted data traffic, such as unencrypted web traffic. This type of provider can also determine information about a device connected to the network by analyzing transmitted user-agent strings, the device’s MAC address, or any identifiers that application or mobile operating system developers transmit in plain text.

OS Vendor

The developers of major operating systems, like Android, have access to a wide range of information about the device. For an Android device to regularly receive updates it must be tied to an account, such as the Gmail account required to access the Google Play Store. In addition to the exceptionally wide range of information about the device that this access provides, many of the bundled applications on phones, including maps, provide a rich stream of location information back to the operating system manufacturer.

The design principles integrated within mobile operating systems vary considerably, with consequences for how much of a user’s communications the vendor sees. For example, on Android, Google Hangout messages are accessible to Google in an unencrypted format, whereas iMessage communications on iOS are encrypted end-to-end, blocking Apple from easily reading the messages. Despite these differences, vendors still receive substantial information about users via avenues like mobile account backup and recovery, updates, map applications, and activities on app stores.

Finally, while tremendous variation exists across handset manufacturers, major manufacturers also have avenues for access to identifying information about users. For example, some major manufacturers offer ‘find my mobile,’ backup services, and updates. Some previous reports have highlighted privacy and security concerns with these services, including cases where personal user data was apparently sent without encryption.

Application Developer

Application developers can access a range of identifiers in the course of providing their services. Many mobile operating systems will reveal which identifiers an application seeks to access, such as phone dialing information, SMS messages, or the device’s GPS; these possible permissions are noted in Table 4. In addition, developers may partner with advertising networks or other third parties, and share their users’ identifiers or personal information with these other parties. As a result, in addition to the apparent collectors of identifiers (i.e. app developers) there are largely hidden collectors, such as those belonging to advertisers and analytics or crash report companies.

Device Tracking by Third Parties Using Identifiers

The many identifiers assigned to our devices form a key part of the operations of mobile and wireless networks. However, a range of vulnerabilities can be exploited by another category of actors: third parties who seek to track or monitor the communications of device owners.

For example, security flaws in the design of the global telephone system enable third parties to silently track the location of any mobile number anywhere in the world, as well as snoop on user activities. At a more local level, businesses are increasingly monitoring the movement of shoppers and foot traffic near and within their stores; some companies use the Wi-Fi MAC address, signal strength, and other mobile device characteristics to identify customers as they browse stores or walk in retail areas. Some attempts have been made by manufacturers to reduce the identifying characteristics of Wi-Fi connectivity by randomizing MAC addresses, but with mixed results.

Data Gathering and Surveillance by State Actors

Governments throughout the world make extensive use of the vulnerabilities and privacy deficits associated with mobile communications to conduct both targeted and widespread surveillance.

We know from a recent case in Libya that the Gaddafi regime leveraged tracking and monitoring on the mobile network as a potent tool for control and repression. Moreover, state-level actors have also hacked SIM card manufacturers’ systems to collect encryption keys, and can collect IMSI and IMEI numbers alongside phone call information. At local levels, some authorities use ‘IMSI-catchers’ to create fake cellular towers for targeted monitoring. As nearby cellular phones connect to these fake towers, users can be identified and their calls and messages monitored.

The applications running on mobile devices are also targeted by state actors. The Canadian Communications Security Establishment intelligence agency reportedly experimented with capturing data that leaked from mobile devices to map and track those devices (and their owners) as they moved around the country. British intelligence officers exploited a popular web browsing application that poorly secured users’ information. Finally, British and American intelligence officers reportedly captured information, such as contact books, that were collected by the application ‘Angry Birds.’

Concluding Remarks

The mobile ecosystem is complex and multi-faceted, making it challenging for ordinary users to evaluate their security and privacy risks. Even security conscious users find it difficult to control the communications from their devices. This working document is intended to highlight only one part part of this environment: the many unique identifiers that are regularly transmitted from our devices. We welcome feedback and input, and hope to update the working document in the future.

Footnotes

1 On CDMA networks, devices may use an ESN (Electronic Serial Number) or an MEID (Mobile Equipment Identifier) for the same purposes

2 To limit transmission of the more sensitive IMSI number, the network uses a temporary number (the Temporary Mobile Subscriber Identity) for most periodic updates.

3 Apple still has access to the UDID; the IFA was developed to reduce Apps access to the UDID while providing tracking information to advertisers.

4 A factory reset results in a new Android Identifier.

5 When a user visits a website, the user’s browser sends a string of text (the ‘user agent identification string’) to the requested web server identifying the user’s web browser, browser version number, operating system and other details about the user’s system.

6 Depending on the OS, apps would typically need to request permissions for this access.

7 In jurisdictions where enhanced emergency calling is being rolled out some providers may be able to access your device GPS output when you make an emergency call.

8 In some cases carriers provide mobile payment options, e.g. Google Play, for online services.

https://citizenlab.ca/2015/05/the-many-identifiers-in-our-pocket-a-primer-on-mobile-privacy-and-security/

_

eof

2 To limit transmission of the more sensitive IMSI number, the network uses a temporary number (the Temporary Mobile Subscriber Identity) for most periodic updates.

3 Apple still has access to the UDID; the IFA was developed to reduce Apps access to the UDID while providing tracking information to advertisers.

4 A factory reset results in a new Android Identifier.

5 When a user visits a website, the user’s browser sends a string of text (the ‘user agent identification string’) to the requested web server identifying the user’s web browser, browser version number, operating system and other details about the user’s system.

6 Depending on the OS, apps would typically need to request permissions for this access.

7 In jurisdictions where enhanced emergency calling is being rolled out some providers may be able to access your device GPS output when you make an emergency call.

8 In some cases carriers provide mobile payment options, e.g. Google Play, for online services.

https://citizenlab.ca/2015/05/the-many-identifiers-in-our-pocket-a-primer-on-mobile-privacy-and-security/

_

eof

Ei kommentteja:

Lähetä kommentti

You are welcome to show your opinion here!